Brian Honigman is a marketing consultant, speaker and freelance writer. For more insights on how to be a better marketer, sign up for Brian Honigman’s weekly newsletter. This post originally appeared on his blog.

New advertising realities are forcing brands that have had nothing to do with media to suddenly become content creators. In the age of content marketing, every brand must learn to think like a media company.

Creating content brings a lot of related concerns along with it. One particularly tricky issue for brands to navigate is the question of authorship.

Many brands shy away from giving individuals credit because they feel that it undercuts the overall marketing objectives this content has. The brands want the credit, so why should anyone else get that recognition?

This fundamental mistake is only made by brands who don’t fully understand the implications of what it means to embrace a content-centric strategy. Publishing is a collaborative effort, and a lack of proper attribution undercuts that spirit and will diminish the effectiveness of the content being produced.

By attempting to reap the most benefit and credit from the content their authors create, brands actually undermine the very element that resonates with people and makes the content any good in the first place. As Gabe Kleinman, head of Product Marketing at Medium put it perfectly:

Consumers are savvy to content marketing, and company authorship in the byline only furthers skepticism, even when the content is good. So when it is good, companies should embrace the fact that writers are behind it. Attributing these stories to authors makes them more genuine, resonant, and compelling – and therefore more likely to be read.

Brands Should Claim Patronage, Not Authorship

In a blog post I wrote a while back, I argued that in order to succeed at social media brands must be self-aware.

At the crux of my argument was the clear fact that brands are not people. Regardless of what the Supreme Court says, nobody looks at brands as being the same as individuals. When brands try and pretend to act like people they end up fooling no one and alienating their audience.

Denying individual content creators authorship credit is mostly done so that brands can claim authorship for themselves. However, brands are not people and can’t really author anything. Trying to take credit doesn’t make much sense if you’re fundamentally incapable of receiving credit.

Given this fact, brands should simply take credit for what they’re actually doing. What brands are really doing is providing a patronagemodel.

Patronage is the support or financial aid an organization or individual provides to another. Perhaps the most famous example of the patronage model is the now historic art funded by the Medici family in 15th century Florence.

Cosimo de Medici: The Original Content Marketer?

While the Medici’s became famous for basically funding the Renaissance, that was not their principle function in Florence. They were bankers and their core business was essentially running the finances of the city.

While they didn’t have to do marketing in the traditional sense, the Medici understood that the more they established their reputation (as well as the clout of the city of Florence as a whole) the more trust they would build around their business.

Here we are centuries later, yet the lessons of the Medicis are as relevant as ever. Every company, brand and organization now relies on a community, and the more they can build, improve and contribute to their community’s growth, the better their business becomes.

The reason what we do is called marketing is because the discipline is all about either identifying or creating a market for your product or service. Content marketing is building this community using content. Content is a nebulous term, but what it really means is just material with value and substance.

Organizations who understand content marketing know that they need to find people who are capable of creating things (articles, videos, images, tweets…whatever) that foster and strengthen the community around their product or service.

They don’t claim to have made this stuff, per se, but they can certainly claim they sponsored it. They can do so because it’s obvious that they made this contribution possible and equally apparent why they made it possible.

Brands Need to Think Like Publishers

A few weeks ago I wrote a post outlining my Content Marketing Predictions for 2015. One of my core predictions was that 2015 would see more brands becoming publishers.

In light of this patronage model, the role of brands as publishing houses seems as close of a fit to the old patronage system as modern times will allow.

Brands that are attempting to build out an editorial team, but still want to retain sole authorship of their content are missing the point. Being a publisher doesn’t mean that you are the one creating the content, it simply means that you are providing the means for creating and disseminating that content.

The New York Times mentions their brand exactly once. If they’re not claiming authorship of every piece, neither should you.

It’s a subtle but fundamental difference. Can you imagine if the New York Times replaced all the journalist bylines with their own logo and claimed they wrote every article? Of course not. You don’t read something by the New York Times you read something in the New York Times.

The reason we trust the New York Times as a brand is because they only hire excellent content creators and act as the arbiter of what makes it into their publication. Having them act as both author and arbiter would render both of these functions useless.

Brands that understand content marketing fundamentally understand this principle.

Back in 2012, Mashable put out a fantastic article highlighting the brilliance of Red Bull’s content marketing strategy. This quote from one of the writers for their magazine The Red Bulletin underscores my point.

“I worked independently and had pretty much complete editorial freedom,” says Alison Smith. [RedBull Journalist] “I don’t recall ever being questioned about the work I produced, and was very much in the mindset of a freelance journalist. That’s what my card said, in fact, ‘freelance journalist,’ even though it had a Red Bull office number and cell.

Red Bull provides great stuff to their community and the positive reputation comes naturally.

What Redbull understood then –and what has made their content marketing so successful since– is that individual authorial reputation actually enhances your message.

One writer put it succinctly: “Just because Red Bull is a brand, it doesn’t mean that The Red Bulletin is a vanity project with minimal editorial control.”

Red Bull stamping their name on every single article would be the very epitome of vanity, and it would also signal to the reader that there is no editorial integrity. It’s meaningless to say you “editorialize” when you author the piece as well.

Another example of this principle applied successfully is whatEkaterina Walter did while she worked at Intel. The fact that she put out successful industry content, mentioned that she worked at Intel and occasionally incorporated themes related to the companies offerings and mission caused a lot of the good-will garnered by her individual efforts to be transmitted to Intel itself.

How much more potent then is the good-will from individual authors writing directly under your patronage?

Be Afraid to Give Individual Authorship (Then Do it Anyways)

Brands have quite a few reasons to be concerned about giving authorship credit to individuals. Chief amongst these concerns is that they won’t get their due credit, which I hope by this point I’ve convinced you is off base.

There are some legitimate concerns though. First of all, not having control over what these authors say can lead to potentially damaging situations; and second of all, what happens when this author who has built this reputation suddenly decides to leave your company? Won’t he or she take the good-will they contributed to your brand right along with them?

Let’s tackle the latter of these concerns first. While this worry is understandable, the previous story about Ekaterina Walter’s time at Intel should pretty much put it to rest.

Walter contributed good-will to Intel even after moving on to other roles at other organizations by continuing to build her reputation as an industry thought leader with the release of her two books, her continued contributions to leading business publications and numerous speaking engagements, all of which have been greatly influenced by her time as Intel employee.

If your content creator is associated with your brand’s content directly, then the positive reputation they gave you will follow them around as an ongoing representative of your brand.

As far as the worry that an individual author could ruin your reputation goes, that is easily remedied. The simplest way to mitigate this risk is to put a disclaimer on every single post. In addition, your company should write a detailed social media or content policy outlining best practices and make all contributors sign before authoring any content on your company’s behalf.

These guidelines aren’t meant to set unrealistic limitations for your content creators, but instead create a framework for what successful content creation and distribution at your organization looks like that benefits all parties appropriately.

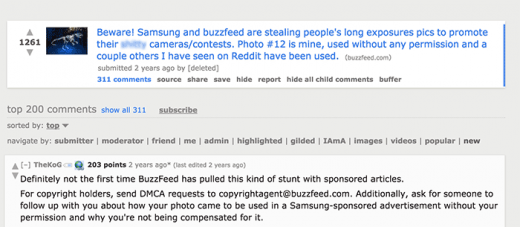

In addition, as much as brands might fear for their reputation when giving up total authorial control, the risk runs both ways. If your brand claims total authorship, then screws up, the blame lands squarely on you. This is exactly what happened when Samsung stole photos from Imgur for their BuzzFeed sponsored post then got called out on Reddit.

Notice how the blame falls squarely on Samsung here.

Content Marketing is a Collaborative Effort

Content marketing is not a tactic or even a strategy – it’s an ethos. And the ethos of content creators (and really creatives in general) is that of collaborative spirit, credit and respect. Brands that think they can just sprinkle content marketing on top of their old ways are mislead.

Doing something only for the sake of credit undercuts the very core of what great content marketing is. Brands compelled to keep the credit for themselves not only misunderstand content marketing. They misunderstand themselves.

So if you’ve read this far looking for an answer to the authorship question, the answer is that authorship shouldn’t be a question for brands – and if it is a question you’re asking, you should probably start questioning your brand’s entire approach.

Read Next: How to tackle content marketing on a budget

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.