When you think about it, the “gig economy” is based on liability — or lack thereof. Predicated on the idea that companies can make big bucks on being “agile,” “flexible,” and “on-demand,” what we see in reality is that this is possible through sidestepping, pushing or outright ignoring liability at crucial points in business service.

Today, a post on Medium brought this situation painfully to light. Entitled ‘Living and Dying on Airbnb,’ writer Zak Stone speaks painfully and candidly about the freak accident on an Airbnb property that killed his father. Although Stone and his family ultimately chose not to pursue legal action against the company (instead opting on a settlement obtained through the hosts’ insurance policy), he brings up plenty of valid points regarding Airbnb’s attempts to disabuse itself of liability in situations involving fraud, safety and other risky endeavors.

But Airbnb is not a sole actor in these behaviors. It is not the only company in the gig economy to have first-hand experience with death. One particularly noteworthy case involved another huge player in the on-demand world, Uber — the company settled out of court on a damaging lawsuit involving the wrongful death of a six-year-old girl who was crossing the street with her brother in San Francisco. The details of the settlement, as well as any terms of the agreement made between the girl’s family and Uber, remain confidential.

More wrongful deaths. Assaults, rapes and thefts. The list of accidents and crimes found in participating in the gig economy are relatively easy Google searches.

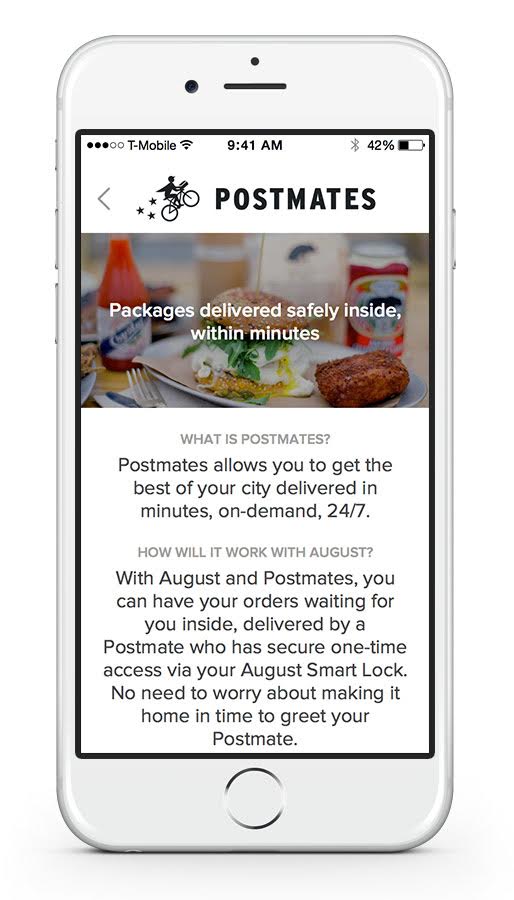

But it is not just in the liability for its users that the gig economy fails to measure up — it also often puts its very employees in unprotected spaces. Increasingly more companies are moving their part-time workers into full-time roles, offering benefits and other stable features of your average job. Of course, this is also a reactive measure: Uber, Lyft, Postmates and other companies are becoming increasingly locked in battles over how they treat and classify their employees. It is a huge factor into what killed former Silicon Valley darling Homejoy (although an excellent piece from BackChannel’s Chrissy Farr does indicate there were other troubles afoot).

How is it that gig economy companies can claim no liability for accidents, crimes and even employee welfare? The core of the issue is semantics. Stone articulates the issue by pointing out Airbnb’s self-claimed status as a “marketplace” or a “platform.” This kind of speech comes up frequently when speaking about gig-economy jobs. Airbnb, Uber, Postmates, and other services can be reduced to glorified Classified ads. In short, you are choosing to do one-to-one business with your driver, Ikea furniture builder, house cleaner or apartment host — the companies just offer the “verification” and “screening” to make the platform experience more pleasurable and offer peace of mind.

But it’s a fallacy to consider that the screening or measures taken by gig economy companies as a guarantee. Uber in particular has been targeted for its screening policies, which it claims are sufficient yet lack what some believe to be crucial fingerprint scans. Additionally, whether there’s unsatisfactory table construction or accidental injury, there’s little recourse a user can bring to the company beyond leaving an unsatisfactory review and hoping the company’s customer service will own up to righting a wrong.

It’s another aspect of Stone’s first-hand account that makes the whole thing so shocking — the lengths at which Airbnb was willing to go to keep the story (and likely the stories of other users who have suffered harm) out of the way of public knowledge. The company is willing to tout how much it pays in taxes — just as other companies are open to speaking about how many satisfied customers or other fun facts they have in their marketing documents — but is still opaque about safety reports.

In a perfect world, these companies would issue safety reports. They would provide more stringent requirements to their fleet. They would also, when applicable, assume liability of that fleet by making them full employees instead of contractors. But doing so would not make them marketplaces. It would not make them platforms. And it very likely would take the juice out of the bottom line.

This is a world that we have created for ourselves: in embracing convenience, we have assumed risk. But that does not mean that this issue is unworkable, unfixable. Rather, we must learn to understand what it means to be a conscientious consumer in the use of these apps and these companies.

I believe that the next few years will be critical in determining the standards by which we hold these companies to in order to ensure they offer good business in good faith. Primarily through legislature, but also through social pressure. We live in a world where we vote with our wallets, and that is not something to be taken lightly.

We can — and we should — do something. At least before these companies become too big to fail.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.