The idea of selling your personal data isn’t one that sits well with most people, yet. Nonetheless, most people are doing so whether they know it or not. Those free social media networks that take massive corporations thousands of servers to keep running day-in, day-out are in most senses buying your data by providing you with a service you want.

The problem for the individual whenever the notion of selling your personal data (or whether you are getting a good deal from the equation) comes up, is that there’s rarely a definitive answer to how much it could be worth or how you could even sell it.

From the other side of the equation (marketers, brands and virtually any other company), the problem is that personal data collection today remains a largely contentious activity, with vast quantities being recorded directly at the point the service is being used. One example of this is the cookies that collect data as you browse around the Web.

That’s only the obvious stuff though.

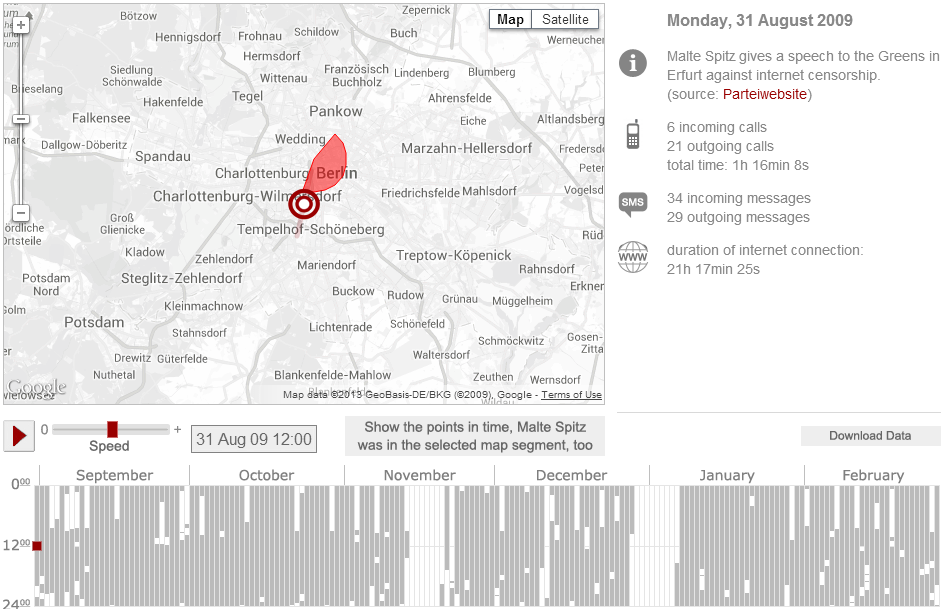

Take the case of Malte Spitz, a German Green Party politician who wanted to know exactly how much and what data his phone provider held on him – in this case, as a result of an EU Data Retention Directive that requires ISPs and phone operators to keep communication records for between six months and two years.

After months of lobbying his phone company (Deutsche Telecom in Germany, for the record) it relented and provided Spitz with a copy of his data for the requested six months. All 36,000 lines of it on one CD.

Knowing that your phone provider collects data on you probably isn’t a shock, but it might be more surprising to see what can be done with just six months of mobile phone usage data. We highly recommend checking out his data for a better look at the scary level of detailed knowledge about an individual that can be achieved through six months of phone data and nothing else.

“Self-determination and living in the digital age is no contradiction, but you have to fight for your self-determination today. Tell your friends, privacy is the value of the 21st century and it’s not outdated,” Spitz said at a TED talk in June last year.

A middle ground

So the idea of just selling our data freely to anyone who wants it isn’t perhaps the best, but there’s an emerging middle ground between being knowingly (or unknowingly) digitally stalked by brands and businesses and sharing nothing at all – and therefore getting no benefit from its collection.

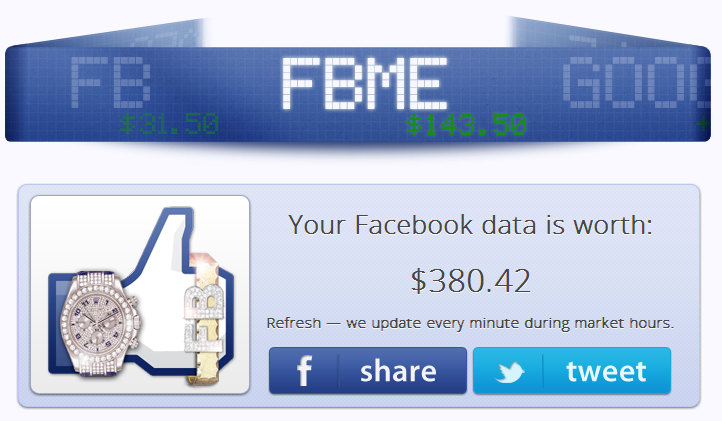

While it’s difficult to get an accurate reading on how much our individual data is worth to various companies, consider for a second that services like Facebook are potentially making hundreds of dollars each year off each and every user. When you have a billion person user base, that can add up pretty quickly.

Even though these estimates can vary pretty wildly depending on the tool you use to get an estimation, it’s clearly an imbalanced situation that can’t continue in its current state.

The World Economic Forum (WEF), in a report back at the start of 2011, already identified that personal data is becoming a new economic “asset class” and will act as a valuable resource that “will touch all aspects of society”.

However, it too recognized that “increasing the control that individuals have over the manner in which their personal data is collected, managed and shared” will be key to spurring the development of new services and applications.

What saleable personal data is currently collected?

While you might not share the contents of your emails online, there’s plenty of data on you out there already – and we’re not talking about the highly secretive government data collection programmes like PRISM.

Data brokers will scour public documents like birth and vehicle records to find out details like age, gender, address and ethnicity – things that are all relatively easy to come across and usually a matter of public record.

Then there are the online services that you access and use (often) for free in exchange for your data. So, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn etc., these are all sites that are built around the idea of the more info you fill in, the better your experience will be.

On these sorts of sites, you’ll give out personal information, income, gender, occupation, things you like and dislike, personality info and a host of other information. Not all of them will sell data, nor intentionally pass data along to other websites, although lots do. The same is true for any site that requires registration, generally speaking.

Anonymized, grouped data

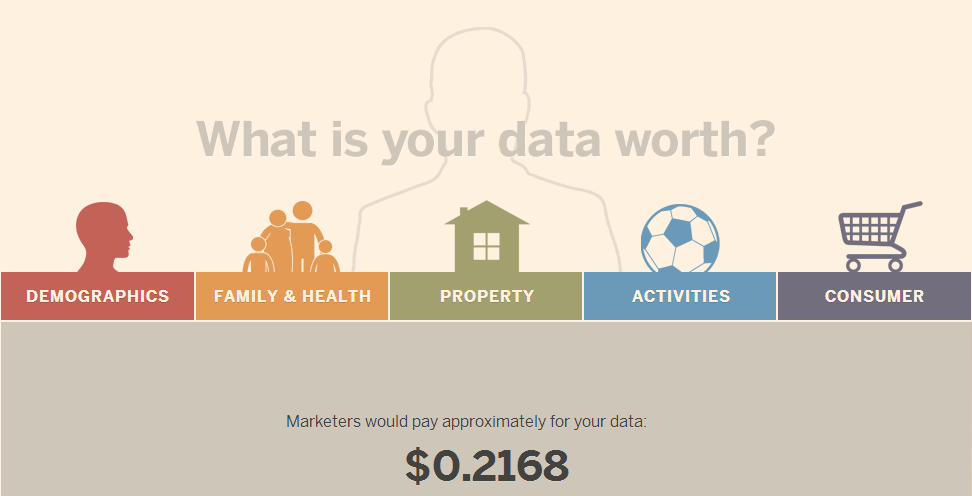

In June, the Financial Times launched a personal data calculator to give individuals a better idea of what their data is worth. However, the figures it returns relate to the relative value of a regular individual’s data when sold as part of a bulk of anonymized data. For obvious reasons, anonymous personal data is of less value than knowing full details, and is therefore worth less cash.

Judging from that, my personal data as a non-millionaire, non-home owning, singleton is worth just under $0.22 cents. So, a marketer would typically buy 1,000 profiles of data like mine for just under $220.

So what’s my individual data worth?

As you can see, the value in grouped anonymous data is hardly mind-blowing, but taking it to an individual, identifiable level can massively increase the value.

Take the example of Federico Zannier, who took the value of personal data into his own hands and set up a Kickstarter project to sell all of his personal data, which is around 70 websites, 500 screenshots, 500 webcam images; a recording of all of his mouse cursor movements, GPS location and an application log. All for $2 per day. Buying a bigger package qualifies the purchaser for even more data for their cash, too. For the record, the campaign’s $500 goal was far surpassed and ended up raising more than $2,700 before it closed, showing there is clearly a demand.

Selling your data, one step closer

While that’s a pretty extreme example of selling your personal data, it also sounds like it would be rather time-consuming. However, other platforms do now exist and are looking to make that process easier and balance more of the power in the user’s hands by allowing them exactly what will be disclosed, whether it will be personally identifiable and what it’s worth.

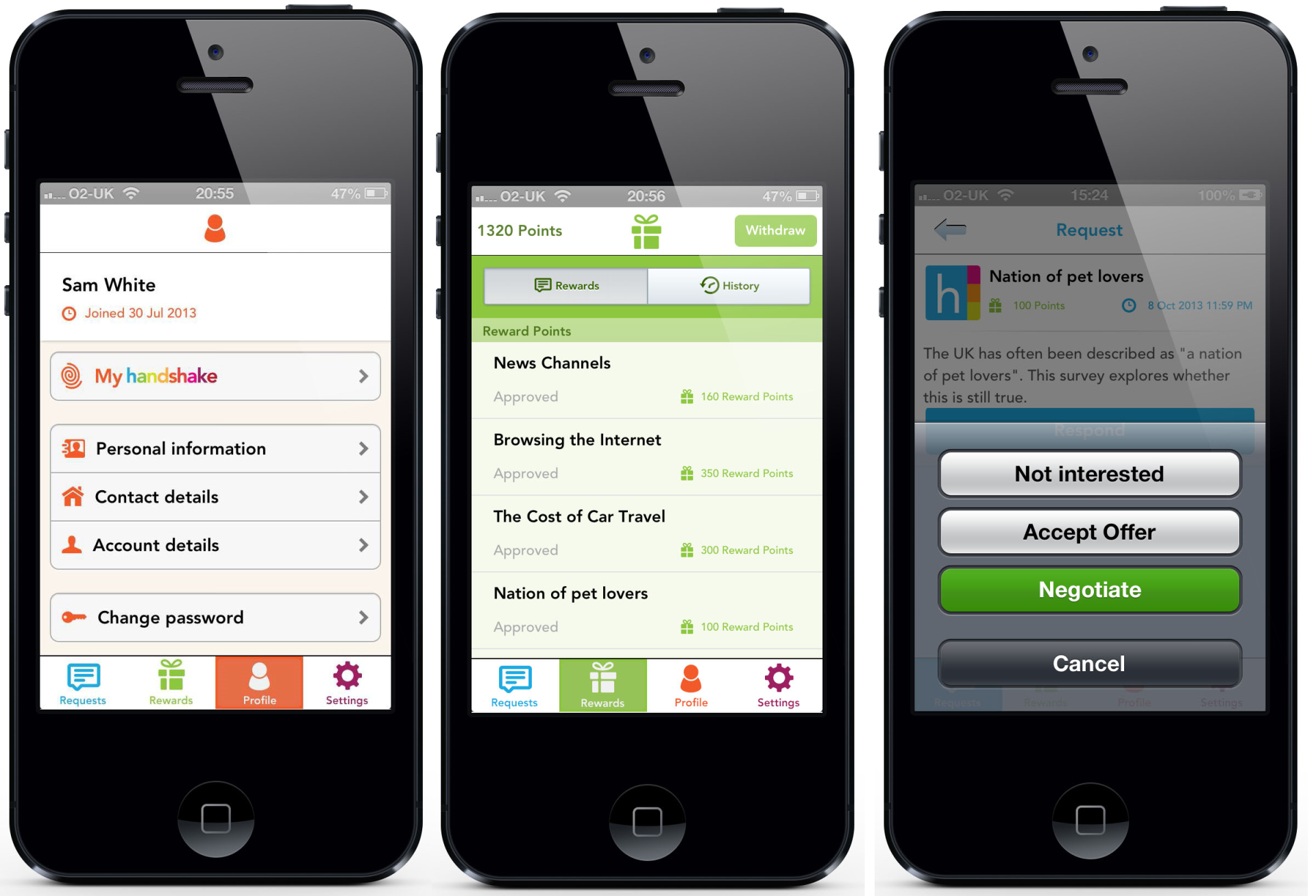

For example, a new company called Handshake is pitching its personal data platform as a way for end-users to get real money in exchange for some of their data and a bit of their time.

It wants users to sign up and enter as many details as they choose. It then rewards them for sharing that data with businesses that are running campaigns on the platform. There’s also the option of keeping all of the data anonymous too, but if they do it’s worth a lot less cash.

The sort of data Handshake wants is the usual personal information, like gender, income and occupation but it also wants users to fill out short client surveys (traditional ones, as well as real-time surveys that might pop-up based on location, for example), purchase intent queries and personality profiles of the respondents.

It also goes a bit beyond this, though, and gives the option of running campaigns that ask for far more detailed quantified self data like food intake, location, sleeping habits and purchases (scanned receipts etc) among others. As well as just allowing users to accept or reject an offer of exchanging data for cash, it also provides the option to haggle a little bit, if you think your data is worth more than the project is offering.

If you’re willing to spend the time, and share the data, an average individual on the platform could be netting between £1,000 ($1,600) and £5,000 ($8,000) per year on average, CEO of Handshake, Duncan White, explained to us. If you take the value of high net worth people out of that average and the figure becomes £3,500 ($5,600) per year. But if you do happen to be a high net worth individual with some time (and inclination) to use the platform, it could make you around £15,000 ($24,000) per year better off.

To break that headline figure down for a minute, Handshake explained that the average £5,000 ($8,000) per year amount is based on the example of a 50-year old individual earning between £30,000 ($48,000) and £45,000 ($72,000) per year, that’s tech savvy, aware of privacy and willing to use the platform very frequently. In those circumstances they would need to:

- Fills out 150 surveys a year

- Takes part in 6 focus groups

- Shares details of 48 experiences

- Shares details of 42 intentions to buy products

- Shares first party data 12 times a year

Of course, with the explosion in the ability to capture, store and analyse data, Handshake isn’t the only company trying to work out how to empower consumers with it.

Similar, but with a twist

Enliken is another company that came to market with a similar proposition – offering consumers the option of exchanging their data for discounts or charitable donations on their behalf – but has since changed tack due to a lack of readiness from businesses and brands.

“What we eventually found was that the counter parties (mostly publishers and online retailers) weren’t ready to start transacting with data, either technologically or from a brand perspective, Marc Guldimann, CEO and founder of Enliken told The Next Web.

“Recently we’ve taken a step back and began developing more basic consumer facing data tools for businesses […] the gist is that we want to help businesses be more responsible and transparent with the data they already have before they ask for more.

What data is ‘worth’ can be looked at a couple of ways; what a counter party is willing to pay for it, and the value you can create by using the data. The first example is more obvious, but a lot harder to implement. You need to find a counter party who wants the exact type of data you have for sale, in the format you have available under the terms you offer. It’s very hard to get to scale that way.”

Value beyond cash

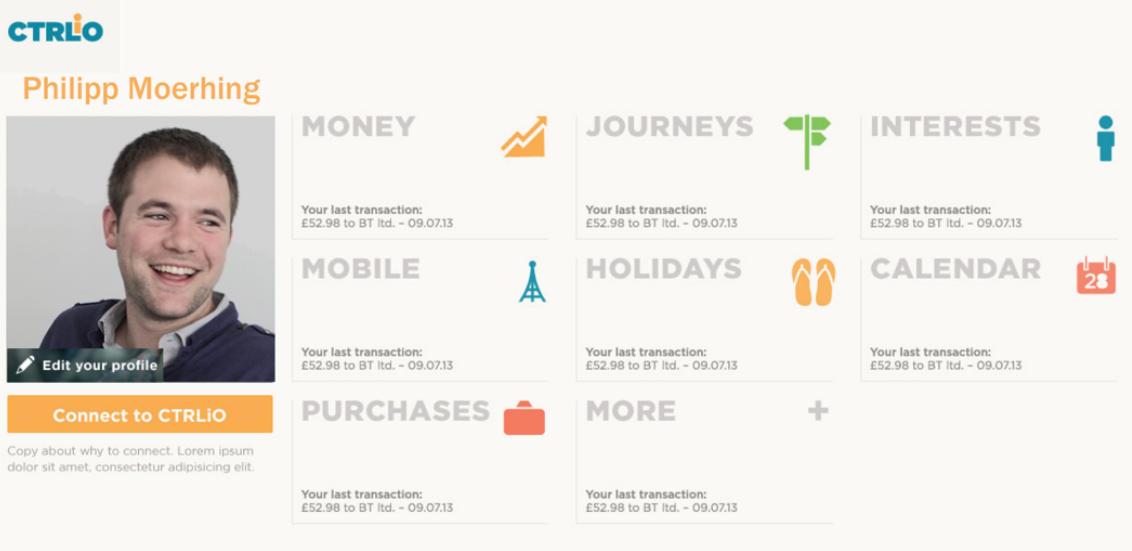

This idea of personal data being worth more than simply money is one being explored by UK-based startup Ctrlio, which is looking to connect the disparate dots of the personal data collection picture as it stands right now.

“In four to five years, half the world won’t care about their data and the other half will. The half that do would have gotten more and more spooked by the stuff that’s going on and will have turned in that time to companies that give them that data back that allow them to not only play and understand it [their data] but also exploit it,” Laurence John, CEO and founder of Ctrlio told us.

Naturally, this is exactly what Ctrlio is looking at doing with its platform.

To give an example of how this could provide value beyond money; imagine going into a phone shop to get a new contract and the retailer offering 10 percent off in exchange for your personal data. How does the retailer work out the precise margin for the value of each customers’ data and should all of them be worth the same?

Once this hurdle has been circumvented, does that 10 percent off the up-front cost seem like a good deal? Wouldn’t it be better to be able to share your data with the company and have them tell you that, “Yes, O2 is a cheaper mobile contract deal but for where you spend most of your time, the reception isn’t very good” than to simply have a phone that rarely works, but costs less than normal?

This is the sort of additional value Ctrlio wants to create from your data by packaging it all up and giving you the tools to explore and understand it – as well as share it with companies you choose.

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges for Ctrlio’s approach, John told us, is that it will take some time for companies to realize that they have more to gain from taking an open approach to consumer data that empowers the end-user than by being closed and tracking users against their will online.

The future of your data

As our ability to collect, store and analyze our data continues to expand, the concern from some parties around these practices will continue to heighten until a point where there is a viable set of tools for consumers to use in order to regain (and retain) control of the collection and sharing process.

Handshake, Enliken and Ctrlio are all taking slightly different approaches towards this goal. Right now, it could be a struggle for any one of them to deliver a step-change in the way businesses use personal data, but the very fact that there are now a handful of companies all focused on giving end users back their own data suggests that it’s certainly an area of growing interest.

It also means that should you choose to sell your data for straight cash or leverage it for something you deem more worthwhile, there are options out there now to facilitate this, which couldn’t be said very long ago at all.

Featured Image Credit – Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.