Artificial intelligence and automation are continuing to drill deeper into our society.

- In the business industry, companies are now utilizing the voice recognition provided by intelligent personal assistants such as Alexa, Cortana, and Siri to speed up their tasks.

- In the transport industry, artificial intelligence is powering the upcoming self-driving cars and helps to manage the flow of traffic.

- In the education sector, artificial intelligence is used to support personalized learning systems.

- In healthcare, new diagnostic tools and decision-support technologies are being powered by artificial intelligence.

- In the retail sector, artificial intelligence is improving the design of warehouse facilities to make the process more efficient.

- In the film industry, artificial intelligence is being used to compose orchestral music and generate short pieces of film

- In the humanitarian sector, artificial intelligence is being used to support the delivery of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Yet, there seems to be a disconnect between the people designing and implementing these systems, and those who will be most affected by the outcome.

The reported median annual salary for an AI programmer in the UK in 2019 is currently around £60,000. Meanwhile, the reported median annual salary for all workers in the UK is reportedly around £36,611.

The result of widespread automation

Automating routine operations presents a lot of benefits. It presents the opportunity for people to move on from repetitive tasks to more rewarding, challenging work that allows them to engage their emotional intelligence.

But currently, this is far from the case. Instead, low skilled workers are finding themselves being continually downgraded into increasingly insecure, low-paid roles. For some people, their jobs have been completely replaced.

In 2013, researchers at Oxford University studied 702 occupational groupings. They discovered that 47% of US workers have a high probability of seeing their jobs automated over the next 20 years. More recently in 2017, a McKinsey report predicted that 30% of ‘work activities’ would be automated by 2030 — a change that is set to affect up to 375 million workers worldwide. That’s a significant number of people.

Throughout history, new waves of technological innovation have always led to a spike in public debates regarding automation. The movement is comparable to the shift away from agricultural societies throughout the Industrial Revolution. Evidence from this can give us some insights to inform policy debates today.

People have been worrying that automation would leave humans without work as far back as the 20th century. In 1950, John F. Kennedy described automation as a ‘problem’ that would result in ‘hardship’ for humans.

15 years later in 1965, an IBM economist said automation would result in a 20-hour workweek. Considering the average American still works an average of 34.4 hours per week, this prediction was clearly quite a way off.

But it took decades to tackle the injustices of the Industrial Revolution. This time, we can’t afford to wait that long.

If employment levels fall significantly enough, there is a fear that Western democracies could resort to authoritarianism, which spread in some countries back in the 1930s following the Great Depression, and as is the case in many countries today that have experienced high levels of income inequality.

The real challenge is managing the transition

Western politics is already becoming increasingly turbulent. Income inequality is slowly beginning to grow even further, contributing to the already shaky political instability. A large proportion of the population will need to retrain for new careers, and they won’t be young — they’ll be middle-aged professionals. Developed economies are likely to be hit hardest by the transition, as increased wage averages increase the incentivization for automation even further.

Automation will vary widely, depending on the industry sector. Jobs in industries such as health care are set to increase to cope with an aging population, while jobs involving manual labor and data processing are set to decline.

It’s impossible to know exactly how many jobs will be affected by AI, as studies give wildly different estimates, depending on the treatment of the input data.

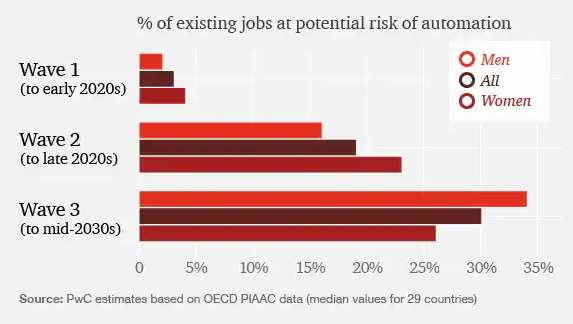

A report by PwC suggests there will be three major waves of automation.

Wave 1 will occur in the early 2020s and is expected to displace a very low proportion of jobs — around 3%.

Wave 2 is expected to arrive in the late 2020s and is expected to displace many jobs in the clerical and administrative sector.

Wave 3 is expected to arrive in the mid-2030s and could result in the automation of up to 30% of today’s jobs — particularly those that involve automotive equipment and machines.

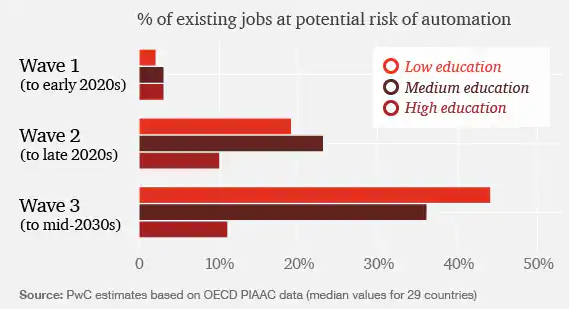

Workers with lower education levels are likely to be much more vulnerable to being replaced by machines:

How can we tackle it?

The McKinsey report used America’s transition away from agriculture during the Industrial Revolution as an example. With the decrease in farming jobs came a significant increase in spending on secondary education and new laws that made attendance compulsory.

In 1910, 18 percent of children between 14 and 17 years of age went to high school. By 1940, 73 percent of children between 14 and 17 years of age went to high school. This increase in education helped to create a booming manufacturing industry.

If we want the future of automation to be successful, it is clear that a similar push is needed today. It’s becoming increasingly clear that AI will not result in the ‘end of work.’ It could create as many jobs as it gets rid of. Instead, the jobs of the future will merely require a different skillset.

Government advice networks need to support more businesses to use machine learning. We need to build skills at all levels —from schools to industry professionals, to undergraduate and postgraduate students.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be the case. In fact, in the last few decades, spending on training and supporting the labor force has been in decline. In addition, many schools are still failing to teach the key concepts of technology to their students.

Automation doesn’t have to be a disaster — but it will be if politicians don’t understand our need for change

If we want technology to benefit everyone instead of further widening inequality, we need to start training our workforce for the future immediately. Inaction will result in even greater division and polarization between communities.

Politicians, trade unions and business leaders need to act now if they want to make sure the result of technological change is good.

This article was originally published on Towards Data Science by Aimee Pearcy, a computer scientist, writer, and campaigner. Her work focuses on human rights issues in the tech industry.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.