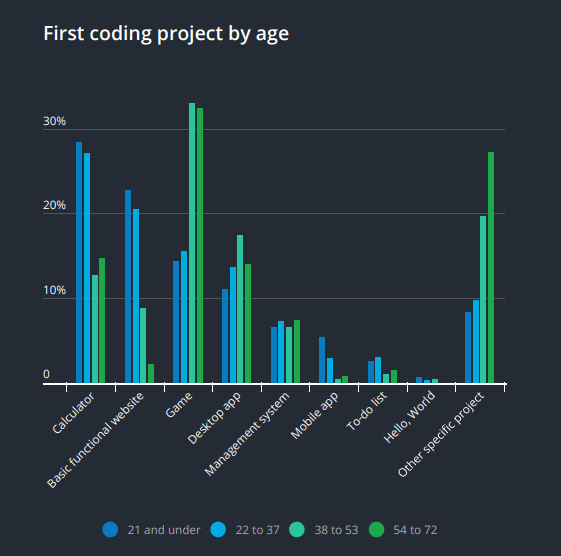

HackerRank released its 2019 Developer Skills report this week. The report, which includes data from over 71,000 coders, paints a picture of stark generational differences. For instance, did you know different generations of coders built completely different things for their first program?

Older developers, particularly those in the 38-53 and the 54-72 age brackets, overwhelmingly tended to create games as their first programming project. Those currently aged 21 and under, however, tended to build calculators as their first programming projects. So, what gives?

Eager to figure out why, TNW reached out to Jim Wilson, Pluralsight author and a veteran software developer with more than thirty years experience under his belt. Wilson reckons the vast gulf between generations is due to the fact that computers — and crucially, our understanding of what a computer does — has fundamentally changed.

“The change over the years reflects our changing experience with computers and in turn the best way to create a relatable learning experience for students. In 1982, when I was a high school junior sitting in my first computer programming course, a computer seemed completely unrelatable to me,” Wilson told me.

In order to relate to it, I needed to be able to engage with it, experience it. For me, creating a calculator as my first project would have just proliferated my feeling of computers being unrelatable number-crunching devices. But a game, now that seemed cool. Writing my first program, a simple game that involved using the arrow keys to move through a maze and then show some very simple graphics at the end, changed that feeling. It made the computer something that I could interact with, touch, and experience.

Alex Klein, CEO and co-founder of Kano, reckons the nature of early computers had something to do with this trend towards game creation. Many programs required the user to copy the code line-by-line from written material, in order to run. This gave novice developers an opportunity to analyze how programs were built, and to make their own modifications.

“I think it was a game for the older generation because there was so much less coding education material available at the time. Instead, the small minority of people with computers were also, themselves, technical to begin with, and even operating the machine required some code. Classically, loading up games line by line on a Spectrum or Commodore was one of the only purely entertaining things a computer could do (no streaming, for instance) — so makes sense that the first program you wrote would be a game,” Klein said.

Although computers were novel and exciting during the 1980’s, things are a different now. Computers are, in a word, ubiquitous.

Most of us carry a computer with us wherever we go, in the form of a smartphone. Computers facilitate entertainment, and connect us to our friends. In 2019, there’s no need to make computers relatable or interesting. They already are.

“For those much younger than me, computers have always, or at least nearly always, been a part of their life. A computer is something they interact with, touch and experience every day. For these students, the way to create a relatable learning experience is to demystify the computer’s inner workings, to show them just what’s happening within that device that they use every day,” Wilson said.

The simple programming tasks required of a calculator app such as gathering input, performing appropriate logic, and presenting the results to the user, take the student inside the computer. These tasks demystify the inner workings of a device that they use every day.

This is a sentiment Klein happens to agree with. “Today because computers do so many more things so much faster, it makes sense that a first program would strip down to the very basics — a calculator — to shine a light on first principles rather than hacking what exists,” he said.

So, what about the next generation? Wilson predicts that in the future, aspiring coders will build something completely different as their first software project. Thanks to the affordability of devices like the Raspberry Pi, kids will enter software development by building basic Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

“My expectation is that the next generation of students will soon be writing a third kind of first app, a simple device control or automation app. As these students grow up surrounded by home automation systems and intelligent devices, the way to create that relatable learning experience is again to demystify the inner workings of the computers that they live with every day,” he said.

This is a plausible hypothesis. Already, there are a swathe of devices that teach programming through an electronics-first approach, like the Piper Computer Kit, which was updated earlier this week.

“Thanks to the wide availability of simple programmable devices like Raspberry PI and Internet of Things platforms like Android Things, providing just such a learning experience is within easy reach,” Wilson added.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.