Animal Crossing: New Horizons for the Nintendo Switch launched last week and it’s been taking this weird quarantined world of ours by storm. It’s the second biggest launch on the Switch ever in terms of physical sales in the UK (after Pokemon Sword & Shield), and every Switch owner I know won’t shut up about it.

I’m no better than them. I got the game last Friday and I’ve barely stopped playing since — just like I couldn’t stop playing Animal Crossing: Wild World for the Nintendo DS back when I was 17.

So what is Animal Crossing, you ask? Well… it’s incredibly complicated and simple at the same time. I don’t have a good shorthand to describe it, and there’s no other game like it. Wikipedia calls it a ‘social simulation video game,’ but I don’t think that’s accurate.

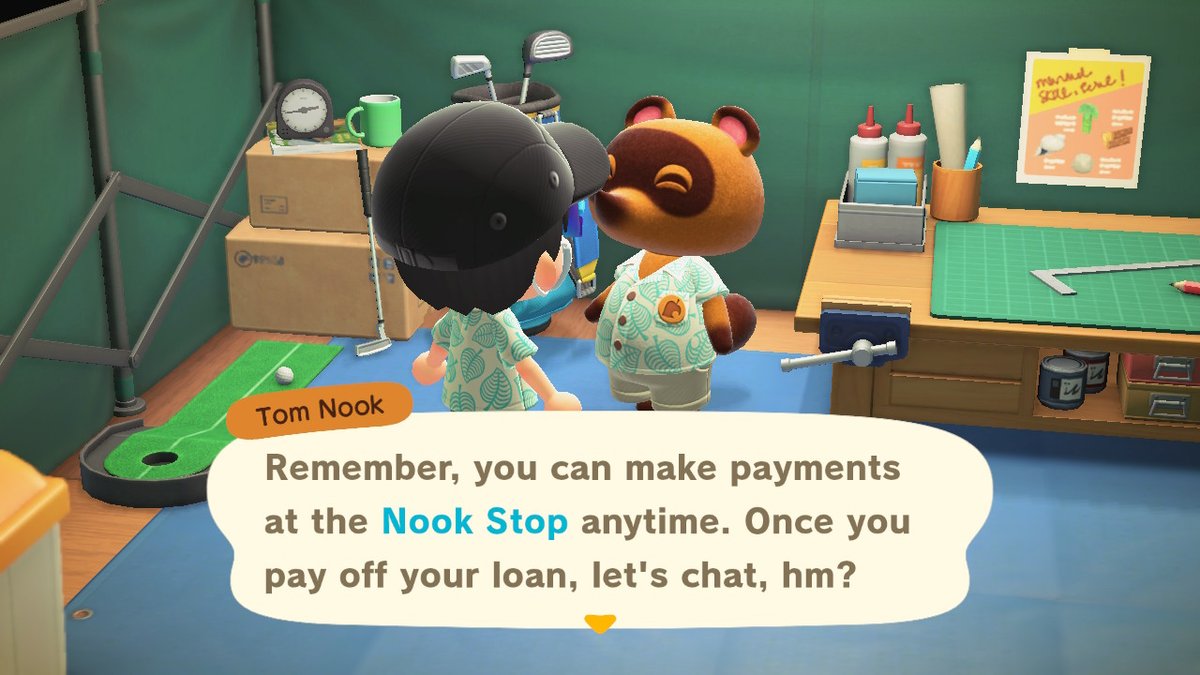

I can tell you what you do in Animal Crossing: You do chores. To pay off a mortgage. Chores like chopping wood, catching fish, and plucking fruit. You pay off your mortgage so you can get a bigger house, with a bigger mortgage.

You fill your house with furniture, you collect fossils to donate to the museum, you decorate, you garden. It’s all very mundane and chill. There’s no challenge, no game-over. Everything is cute, and nothing is stressful.

It’s also the opposite of what I normally like about video games. I play frustrating games like Dark Souls and DOOM Eternal, because I’m a sadomasochist and I want my games to punish me for playing them. Animal Crossing never punishes.

Long story short: I love Animal Crossing but I don’t know why — and that’s a problem when you’re tasked with reviewing it.

I had no choice but to get some people who are way smarter than me to do my job for me. I hopped on Twitter, and DM’d some friends in the game industry to help me answer my two big questions: Why is Animal Crossing so addictive? And why don’t more games like this get made?

So how does Animal Crossing get people so hooked?

Martijn van der Meulen, co-founder and development director at Snap Finger Click with nearly two decades of game industry experience, says “It’s the pressure of wanting to do the best you can for your village and your villagers. Collecting the fruits, catching the fish – you want to get as much as you can every day. It feels like a waste if you don’t shake one of the trees! That’s a few more bells you could’ve given to [your loan shark landlord] Tom Nook.”

Daily tasks and appointments are a big part of the loop in Animal Crossing. In order to get as much as you can out of the game, you’ll have to jump in every day to check on your villagers to make sure they’re happy.

Van der Meulen says, ”If you don’t visit your neighbor, they might leave and that’s personal. That would really hurt your feelings. Everything about the game makes you want to do your best which means spending as much time in it as possible. Animal Crossing has almost perfected the distribution of these tasks.”

Sam Sharma, a veteran game producer who’s currently working on a secret project at Electronic Arts, believes New Horizons couldn’t have come out at a better time. He says “there’s definitely the comfort of doing daily tasks that we’ve been missing in self-isolation, that makes it a relaxing escape.”

He continues, “Even without that though, the game gives a lot of autonomy to the player, to discover and explore. [Animal Crossing] has completion levels and checklists for anything you can do.”

He says this “creates a virtuous cycle for both kinds of players. Those that like structured tasks have an unending list of things to accomplish – all of which are rewarding, and those that like exploration and discovery are constantly rewarded for their curiosity.”

Dennis van den Broek, senior designer at Guerrilla Games, expands; “Looking at it from a game design perspective – it has a level of psychology involved.”

He draws a comparison with free-to-play mobile games: “They often establish a hook which keeps you returning to it. The basic principle behind this is the player gets a feeling of accomplishment and euphoria when doing small tasks, constantly repeating this, and giving the player simple rewards (things like a different color wallpaper).” He says this is exactly how mobile games get players addicted.

Van den Broek says that once this addiction has been established, these games ramp up the time it takes to get rewards, and push you towards paying to cut down the wait by spending real money. Animal Crossing doesn’t let you use real money, but the cycle is similar otherwise.

“Once the baseline is established, they scale it up. It takes longer to get a reward, but the reward itself is bigger. This means you aren’t hooked on paying your mortgage, but you’re actually addicted to getting rewards.”

Eline Muijres, who’s currently a producer at Mi’pu’mi Games after a long stint as the communications manager at the Dutch Game Garden, says it’s the ultimate game for completionists like her. “Collecting animals, decorating houses, fashion design, meeting neighbors, all at your own pace without time pressure.” She adds that she loves the puns. I agree, the puns are so good that even a pun-skeptic like myself gets a chuckle out of them.

Rami Ismail, co-founder at Vlambeer and renowned industry spokesperson, says that Animal Crossing does three things very well:

“First, it’s a game about you – it gives you full ownership of your island, along with ways to make it feel “yours” very quickly, and finally, a loose structure to play. In Animal Crossing, you decide the goals, you set the pace, you decide the priorities – and that’s how it’s meant to be played.”

His second point is the aforementioned daily tasks. He says Animal Crossing “subtly uses a form of FOMO,” the mechanic a lot of mobile free-to-play games use to bring you back each day. “Animal Crossing expertly uses that by having you check back the next day for things”, Rami says.

The final trick Animal Crossing uses is its social aspect. “Players want their island to look nice and feel nice. The game allows you to customize your island to the minute details, which means that you can be judged by all [of those little details].”

In addition, Ismail says “there’s actually a bunch of existential and social fear built into the core of the game design, but since it manifests in what is effectively a pleasant grind, I don’t think anyone really minds.”

Rami has a final word on what he believes makes Animal Crossing feel so good to play: “Animal Crossing is also expertly tuned into what creates joy. Small animations, messages of thanks, little progressions, rare occurrences – it’s all there to give a sense of joy and discovery. Nothing can actually harm you in the game – and everything in the game builds towards something.”

“Together with a sense of progression – whether it’s being able to drop off items faster, get more places to find cool stuff, or having a tent evolve into a building, it all combines into play sessions that are frequently almost entirely purely joyful – even if you get stung by a bee.”

The previous proper Animal Crossing came out eight years ago. In the meantime, we’ve had the phenomenal Stardew Valley and Dragon Quest Builders games, but beyond those, titles in this genre seem to be pretty rare, despite its popularity.

Why don’t they make this type of game more often?

Martijn van der Meulen says it’s hard to make a seemingly simple game like Animal Crossing and have people genuinely care about it.

“Animal Crossing has charming characters and a rich world with lots to do. Building a game that your players want to invest their time in takes some careful balancing. It’s also a huge project. When you think about all the mechanics in Animal Crossing, they’re all minigames that have had tons of thought and effort to make them fun. It’s a big risk to try and succeed in this genre.”

Eline Muijres agrees that games like this are deceptively complicated. “My guess is that because the replay value is so high, it’s hard to top existing games. These games have long development times and are complex to make; it might not be worth the risk for most developers.” She says it’s especially risky for smaller indie developers who don’t make free-to-play games.

Sam Sharma thinks there are two major reasons why these games are few and far between.

“It’s possible that the data on building and farming games suggest that the audience size for them is such that the peak of the market hits every three or four years or so.” He adds that the low rate at which these games come out helps to ensure that the audience stays large enough and hungry enough for the next one to get popular.

His second reason is market dominance. “Between Stardew, The Sims, Minecraft, and Farming Simulator – there are games that cater to that audience in a big way and dominate the market for long periods. (The Sims 4 came out in 2014, Stardew Valley released in 2016, and Minecraft in 2009!)”

“Add to that the slow shift of many exploration/building/farming hybrid games to the mobile and free-to-play space, away from consoles; it could mean that it’s a fragmented and saturated market, that it takes a while for a franchise to find a renewed interest big enough for them to release a new iteration.”

“That being said, I see a shift towards more crafting- and exploration-based play in games coming soon, as the events we are going through shape our appetite and the tastes of our game developers. It’ll start with film, as films have shorter development cycles, and then we’ll see the cultural zeitgeist change in games as well.”

Dennis van den Broek disagrees it’s a rare genre; he says they’re just on different platforms, with different revenue models.

“The basis of these games can be found everywhere in mobile games, they just don’t let you spend money up front to get it, and often end up hiding content behind a paywall.”

But he agrees with the rest that these games are harder to produce then you’d think. “Making a game like this requires tremendous effort – you need a LOT of items to fill your world (rewards), and the economy needs to be tested and tweaked to perfection.

In itself, that is a task that can take months to years; as a developer you then want a quick return on your investment.” He concludes that this is why most of these games end up being mobile free-to-play titles.

Rami Ismail tells me developing games like this is like a little puzzle, where nothing really works until everything works. “The economy, the activities, the storylines, the movement, the characters, the pacing, the world – it all has to be tweaked well to even know whether it might work. The mechanics on their own are meaningless.”

And like the rest, Rami emphasizes the perceived market saturation. “It’s one thing to develop in a difficult-to-develop genre that nobody has made a game in, it’s an entirely different thing to make a game in a difficult-to-develop genre in which the universally loved multi-million player game Stardew Valley exists, and where your upcoming competition might be a new [and almost certainly immediately popular] Animal Crossing game.”

I haven’t been able to look at Animal Crossing: New Horizons the same way since these experts explained to me exactly how intricate and well-crafted this seemingly simple game is.

If you have a Switch, I can’t recommend Animal Crossing: New Horizons enough. When you’re stressed out about this nasty virus, Animal Crossing is just the thing to take your mind off it and help you relax. I guarantee you won’t be bored any time soon.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.