As Google faces at least four major antitrust investigations on two continents, internal documents obtained by The Markup show its parent company, Alphabet, has been preparing for this moment for years, telling employees across the massive enterprise that certain language is off limits in all written communications, no matter how casual.

The taboo words include “market,” “barriers to entry,” and “network effects,” which is when products such as social networks become more valuable as more people use them.

“Words matter. Especially in antitrust law,” reads one document titled “Five Rules of Thumb for Written Communications.”

“Alphabet gets sued a lot, and we have our fair share of regulatory investigations,” reads another. “Assume every document will become public.”

The internal documents appear to be part of a self-guided training session for a wide range of the company’s more than 100,000 employees, from engineers to salespeople. One document, titled “Global Competition Policy,” says it applies not only to interns and employees but also to temps, vendors, and contractors.

The documents explain the basics of antitrust law and caution against loose talk that could have implications for government regulators or private lawsuits.

In one of the documents, which appear to be written by the legal team, employees are advised to choose their words carefully and use only third-party data when referencing Google’s “position in search” in sales pitches. They are further cautioned never to print or hand out their slides.

“We use the term ‘User Preference for Google Search’ and never the term market share,” that document says.

Google Search is the company’s most profitable product and, as such, a large target for antitrust regulation. It’s estimated that nine in 10 web searches in the U.S. are completed on Google.

To take action against a company, antitrust regulators must establish that it has a dominant share in a market. The more broadly a market is defined, the easier it is for the company to argue that it has real competition. In the slides, employees are cautioned that defining a market is hard and best avoided.

“These are completely standard competition law compliance trainings that most large companies provide to their employees,” Google spokesperson Julie Tarallo McAlister said in an email. “We instruct employees to compete fairly and build great products, rather than focus or opine on competitors. We’ve had these trainings in place for well over a decade.”

Bad words

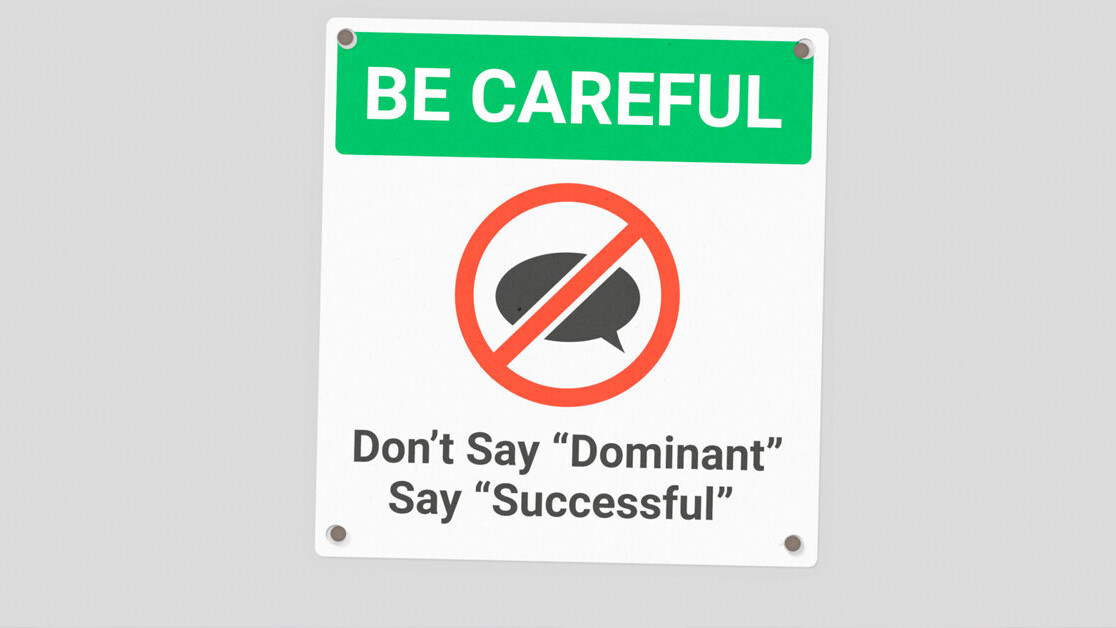

One part of the presentation, subtitled “Communicating Safely,” advises employees on which terms are “Bad” and “Good.”

Instead of “market,” employees may say “industry,” “space,” “area,” or simply cite the region, according to the presentation.

Instead of “network effects,” the presentation suggests “valuable to users.”

And instead of “barriers to entry,” substitute “challenges.”

Alphabet is under investigation by 50 attorneys general and the Department of Justice for potentially abusing its dominance to undermine competition. Its acquisitions, along with those of other major U.S. tech giants, are being reviewed for anticompetitive effects by the Federal Trade Commission. The European Commission announced an “in-depth” investigation of Google’s acquisition of fitness tracker Fitbit and is probing possible antitrust violations regarding Google for Jobs.

McAlister said Google representatives “continue to engage with ongoing investigations” and pointed to a blog post where the company said its deal with Fitbit “will increase choice.”

She also said the company “vigorously” denies claims by Sonos in its patent infringement suit, which alleges that Google first partnered with the company and then copied its technology. Sonos CEO Patrick Spence testified in a hearing before the House Judiciary Committee in January that Google uses its dominance to shut down competition. Google countersued in June, alleging that Sonos infringed on its patents.

Last week, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai faced a grueling 61 questions from lawmakers referencing the company’s dominance in online video, advertising, search, and other areas at a hearing before the House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee.

During the hearing, the chair of the subcommittee, Rep. David Cicilline, mentioned an investigation by The Markup that showed Google Search presented its own results and products above competitors’. He held it up as evidence that Google has turned search into a “walled garden.”

According to a CSPAN transcript of the hearing, Pichai did not say the words “network effects” or “dominant” once and steered clear of defining any particular market. “Google operates in highly competitive and dynamic global markets, in which prices are free or falling, and products are constantly improving,” he said.

Why ‘network effects’ matter

Respected Silicon Valley antitrust lawyers Doug Melamed of Stanford University and Gary Reback of Carr & Ferrell both said it’s not unusual for a giant company such as Alphabet to coach employees to avoid talking about dominance.

“It’s not just trying to hide the truth, it’s really trying to avoid the use of inflammatory language,” said Melamed, a former acting assistant attorney general in charge of the antitrust division at the U.S. Department of Justice. “The use of the word ‘market’ could be very innocent, but it could be misleading and provocative to an antitrust enforcer. Antitrust enforcers really get exercised when they think someone dominates a market.”

Alphabet’s emphasis in training documents on avoiding the term “network effects” is a new one, both lawyers said, and goes to one of the main issues in tech antitrust.

It was one of the concepts the U.S. government and attorneys general from 20 states and the District of Columbia used to prosecute Microsoft for antitrust violations in 1998. They claimed the company broke the law, in part by using its dominance in the PC market to restrict competition by bundling Internet Explorer and other Microsoft products with the Windows operating system. “The barriers that exist to the entry of new competitors or the expansion of smaller existing competitors, including network effects, mean that dominance once achieved cannot readily be reversed,” the DOJ wrote in its complaint.

“Once you admit strong network effects,” said Reback, who has represented competitors in antitrust cases against Google, “then it becomes easier for someone like me to say, ‘You’ve gotten this dominant share through the exploitation of network effects, it’s clear there are high barriers to entry, we’re going to need to break you up or do something strong to stop you from abusing your position.’ ”

Reback represented Netscape early on in the Microsoft case and was the co-author of a 222-page white paper about Microsoft that argued that network effects made tech companies gain market share faster than in other industries, and therefore antitrust regulators must be more aggressive.

Alphabet’s training documents lay out the basic concepts of antitrust law: “Competition laws, aka antitrust laws, are those that govern the conduct of businesses in order to protect fair competition, and, as a result, protect consumers.”

No crushing

The slides also remind employees to keep the focus on how whatever they’re talking about benefits the public, which is a strong defense in antitrust matters: “Pro-tip: when drafting slides, always include at least one that shows how your business decisions will benefit consumers, partners, etc.”

“We are not out to ‘crush,’ ‘kill,’ ‘hurt,’ ‘block,’ or do anything else that might be perceived as evil or unfair,” reads one portion. “Microsoft famously got into trouble when one of their employees threatened to ‘cut off Netscape’s air supply.’ ”

Employees are given “Five rules of thumb for written communications,” according to the documents:

- We’re out to help users, not hurt competitors.

- Our users should always be free to switch, and we don’t lock anyone in.

- We’ve got lots of competitors, so don’t assume we control or dominate any market.

- Don’t try and define a market or estimate our market share.

- Assume every document you generate, including email, will be seen by regulators.

“If they can get their employees to comply with those guidelines, good for them,” said Melamed, the former DOJ antitrust official, who was one of the prosecutors on the Microsoft case. “But most companies’ documents are still filled with all sorts of stuff like this.”

European regulators have already used internal emails against Alphabet. In an earlier investigation, they found emails that indicated that its shopping product’s web traffic doubled in 2008, mostly because it was featured in search listings. The European Commission concluded that the company had abused its dominance and in 2017 fined the company €2.42 billion, a record at the time. “Those emails were quoted selectively and out of context,” McAlister said.

Reback, the antitrust lawyer, said there is a limit to how internal communications can be used, especially when they’re written by lower-level employees. In general, anticompetitive intent is not part of the legal argument, he said. Rather, lawyers for the plaintiff or the government must establish an anticompetitive effect.

Internal communications from higher-level executives that show apparent anticompetitive intent may have more weight—or at least, generate more publicity. The House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee, which held last week’s hearing, collected text messages in which a Facebook executive suggested that CEO Mark Zuckerberg would go into “destroy mode” if Instagram turned down an acquisition offer.

The committee also released an email Zuckerberg wrote musing that “there are network effects around social products” and buying companies like Instagram “will give us a year or more to integrate their dynamics before anyone can get close to their scale again.” He sent another email less than an hour later clarifying that “I didn’t mean to imply that we’d be buying them to prevent them from competing with us in any way.… I’m mostly excited about what the companies could do together if we worked to build what they’ve invented into more people’s experiences.”

During its 2012 antitrust investigation into Google, the FTC also collected emails, some of which Alphabet’s legal team would have frowned at.

In one, Google’s top economist, Hal Varian, celebrated that market research firm Comscore had undervalued Google’s market share.

“From an antitrust perspective,” Varian wrote, “I’m happy to see them underestimate our share.” The FTC ultimately overrode staff recommendations to take legal action against Google and closed the investigation without filing charges.

This article was originally published on The Markup by and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.