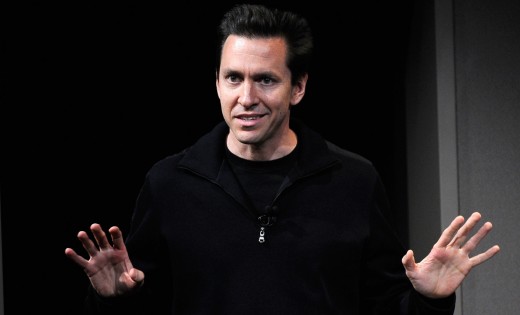

If there were any doubts that Apple CEO Tim Cook was afraid to take the reins and remake the company if necessary, those should now be gone. As of last week, Apple ceased to be the House of Jobs and has become Cook’s domain.

With the removal of iOS chief Scott Forstall and the redistribution of his responsibilities to senior executives like Eddy Cue and Craig Federighi, Cook has eliminated a fiefdom that was proving to be a barrier to progress and cooperation inside the company.

There has been a lot of talk about Maps being the reason that Forstall is leaving. But I’m convinced that it’s not really about Maps, it’s about corporate culture. More specifically, it’s about Cook retooling Apple as a leaner machine that is working together towards a common goal.

Cook sees a future where the majority of people do their computing on mobile platforms first, and he’s preparing Apple for that future.

Pocket first

Apple already makes most of its money on the iPhone, a portable, ultra-personal computer that has transformed the way we use the web and access information. These devices in our pockets are technically still optional but, for all intents and purposes, will shortly become indispensable. The machine that you carry in your bag or that sits on your desk will be a station for getting certain types of work done, and it’s unlikely that they will go away any time soon. But make no mistake: Whatever brand of software is powering your phone or perhaps even small tablet, that thing is going to be your personal computer.

The changes at Apple are designed to make sure that the company works towards the goal of making those personal computers work as seamlessly as possible with your work stations and other devices. With the removal of Forstall, Cook is not assigning a single executive to take over his slot.

Instead, he’s making choices that will foster communication and cooperation between the various compartments of the company needed to pull off a mobile-first Apple. Backend services projects like Siri and Maps are going to Eddy Cue, who has had success revitalizing MobileMe/iCloud and building iTunes in the past.

Cue has proven to be an incredible negotiator who beat the path with the original iTunes movie deals and continues to juggle content providers and Apple’s interests, while still getting fair prices out to you and I. Cue is an enormous factor in Apple’s large advantage when it comes to international content as well.

All of those elements will need to be firing on all cylinders and they’ll need to integrate. Siri, Maps, iTunes, iCloud, media streaming, all of it needs to work together to provide a seamless experience on mobile devices. Google is doing a far better job of this than Apple at the moment, braiding the various Google services together into the strong, tight rope of Google Now.

The fact that the job of overseeing iOS went to current OS X chief Craig Federighi is not coincidental. And it’s not because all of Apple’s computers will run on iOS, because they won’t. All of Apple’s computers actually already run on OS X. iOS is just a highly customized version of it that runs well on mobile devices. And that’s what Cook is structuring the company to take advantage of.

At this point, the biggest challenges that Apple faces are making these items work together more harmoniously. Desktops, laptops, smartphones and tablets, each with their own wheelhouse, but all tied together by a unified design and interface language that allows people to switch between them seamlessly. None of them quite unitaskers, but none of them the mashed-together laptablet hybrids that Microsoft seems to believe are the future.

And throughout, iCloud as the backbone, carrying data and facilitating being able to swap between devices.

Forstall and iOS

From what I understand, Forstall did want the CEO job that went to Cook, but who wouldn’t? In the end, though, it was between Cook and Schiller, the captains. Forstall’s insistence on control of the iOS experience, and unwillingness to break apart and rebuild was what did him in, not the Maps snafu.

Forstall is executive material, and he’s proven that over the last decade. A lot of the chatter about the executive moves have been focused on what he might have ‘done wrong’ or the negative aspects of his personality. But, if you read carefully, the picture emerges of a strong, charismatic leader with a forceful vision and the ability to inspire loyalty of the people under him. Wherever he ends up, he’s going to be a massive asset, and I don’t think he’s gotten enough credit.

But those strengths also ended up creating a situation where the iOS department became a stronghold within Apple. Missteps here and there were tolerated because the general experience was getting better, especially on the back of iCloud, and the developer community continued to grow, which is really the measure of an ecosystem’s health. But the disagreements about the way that iOS should grow, and how Apple should handle its expansion are what eventually led to Forstall’s exit.

Apple has always been a company that is willing to break things that are working perfectly in order to rebuild them anew, or to come up with something markedly better. Yes, it iterates, but it also shatters and re-molds when necessary.

That’s what is needed for iOS now. Putting Ive in charge of Human Interface wasn’t about removing skinning or skeuomorphism, though that will be a likely byproduct. Apple is a company that wants its hardware and software to work together as a harmonious whole. Why wouldn’t it put the same guardian in place for the design language of both?

But if you’re concentrating on re-skinning apps, you’re peering at much too shallow an angle. It’s about breaking apart silos, both in the company and in the structure of iOS.

Touch and progress

Anyone born after roughly 2004 will not remember a world where our most used computers did not have touch interfaces.

There may be something else that replaces it, but for this generation anyway, it’s all about touch. Having a computer, at least of the portable variety, that reacts to touch is the baseline experience, the bare minimum that will be expected. If your screen isn’t alive and doesn’t react at a 1:1 touch level, then don’t even enter the race.

But, because they will enter this world expecting that, more will be needed in order to make the platforms that we work with scale properly with their intellectual and interaction capacity. A large portion of that is going to be better ways to handle interoperability between apps and between devices.

In this department, Google and yes, even Microsoft, are ahead of Apple hands down. Microsoft’s Contracts and Android’s Intents are both examples of ways that these companies are trying to facilitate moving your data around between apps on a device, making it easier to perform more powerful operations using multiple applications.

Apple has nothing like this at the moment. There is a group at Apple working on bringing a cross-process communication framework called XPC over to iOS, but the rumors have been there for months, even stretching back to the announcement of iOS 6.

This would, effectively, open up an official gateway for inter-app communication and allow developers to offer iOS functions of their apps for its own use.

You could trade information and projects back and forth from one app to another, or perform commands using one app’s tools without having to actually open that app. Think processing an image with a Hipstamatic filter immediately after shooting it without ever having to open the app and moving on with your day.

Nearly every developer I’ve mentioned the possibility to has lit up with the possibilities for their apps and for iOS at large. It needs to happen sooner, rather than later.

There is also the continued inability to set different default apps for Mail, different search engines than the three defaults and, of course, a default browser. These are all things that would have hurt, more than helped, in the early days of iOS, when the default options were simply the best available, period.

But iOS is now a mature operating system, with some fantastic third-party options for users.

That’s what the changes at Apple are about, getting these systems working more seamlessly together by breaking down the walls between them.

The way forward

Putting Bob Mansfield in charge of a new Technologies group focused on semiconductors should tell you all you need to know about whether Apple’s DNA is safe. Taking control of the design, if not the manufacturing, of all of their processors allows them to deliver better experiences across the board in performance, form factor and battery life. It’s an enormous undertaking, but one that they’ve already begun to deliver on with the A6 chip in the iPhone 5.

In many ways, this undertaking is a blending of Jobs-era Apple and (hold your hats) Sculley-era Apple. When Apple, under Sculley, made its deal with Acorn and VSLI to craft the ARM6 processor for the original Newton, it did so because there simply wasn’t a good enough option that was power conscious enough to do what they wanted it to do. The legacy of that deal has carried on down to today, and the formation of a formal semiconductor group within Apple is the culmination of everything that has come in between.

And it sets the stage for a new Apple. An Apple that is positioned better than ever to seamlessly integrate the hardware and software portions of the company, as well as its devices. An Apple that might manage to change the world again, right from your pocket.

Image Credits: Shrine of Apple, Justin Sullivan/Getty Images, Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.