Children are struggling with low self-esteem, loneliness or deep levels of unhappiness as a result of using the Web, a new study published by a child support group in the UK suggests.

ChildLine, a free, private counseling hotline for children and teens up to the age of 19, said it was contacted 35,244 times in the last year by children struggling with how to be happy.

In recent years, new problems have emerged in the form of, “cyber-bullying, social media and the desire to copy celebrities as they strive to achieve the ‘perfect’ image” said a spokesperson.

“It is clear that the pressure to keep up with friends and have the perfect life online is adding to the sadness that many young people feel on a daily basis,” said Mairead Monds, ChildLine service manager in Northern Ireland.

The helpline explained the pressures of modern life were creating a generation of children plagued by low-level mental health problems.

In the organization’s 30-year history, general unhappiness is only a recent phenomenon. Previously, self-harm and eating disorders were among the most common causes for children to contact the helpline. Today, these digital issues are on a par.

However, as our digital lives become an even greater part of our identity, it has left a generation of children exposed and vulnerable to the more pernicious affects of a life lived online.

Cyber-bullying pursues kids every second of every day. The illusion of friendship, so easily fabricated online with a Like or Follow has created an existence that grows increasingly hollow while simultaneously ratcheting up the pressure young people feel to maintain perfect versions of themselves through fear of judgement and ridicule.

We have known for years now that adults find it difficult to be happy online. In 1998, Robert Kraut, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, found the more people used the Web, the lonelier and more depressed they felt.

In fact, after people went online for the first time, their sense of happiness and social connectedness dropped, over one to two years, as a direct result of how often they went online.

In 2010, an analysis of forty studies on the topic went further: Web use had a small, but significant detrimental effect on our overall well-being. One experiment concluded that Facebook could even cause problems in relationships by increasing feelings of jealousy.

Even then, the Web was seen as a problem. But today, in 2016, the sheer level of commitment to the various social networks we partake in is add fuel to this slow burning fire. In 2015, there were 20 major sites that catered exclusively for people sharing content with each other, according to Statista.

Buried deep inside social networks is a phenomenon social-psychologists call social comparison. It posits that we determine our own social and personal worth based on how we stack up against others. So we estimate how attractive we are, or clever or successful by placing our relative ideas of ourselves and ask others to approve or reject that estimation.

Psychologists such as Leon Festinger believe that our desire to compare ourselves to others is a drive on a par with thirst or hunger. It’s something I know I have felt when I’ve not checked my Instagram feed for a few days.

However, the difference is, most adults were alive before the internet existed. Relationships were always in person and the intensity of those friendships was dictated to us by how far someone lived from our house.

Of course, there was bullying and abuse – I suffered from it multiple times – but you could escape by simply removing yourself physically from the situation. Children today do not have such a luxury when a smartphone goes everywhere they do.

As part of my training as a psychotherapist we studied the three types of comparison we engage in: self-evaluation, self-improvement and self-enhancement.

When we self-evaluate we gather information about ourselves by comparing our attributes to others – how fast a runner you are, for example. Self-improvement comparisons are used to learn how to improve a particular characteristic or for problem solving (e.g. How could I learn from her to be more attractive).

Self-enhancement comes into play when we deem things around us as inferior to help maintain a more positive image of ourselves, i.e. he may be really good looking, but he’s an idiot. It’s this last one that is so crucial to young adults forming a solid base to how they identify themselves.

As adults we have, mostly, developed a sense of self rigid enough to withstand the barrage of opportunities to see ourselves negatively when we look at others on social networks.

Children however, have not learned that skill. They are just starting out on the epic journey of trying to figure out, “Who the hell am I?”

But from day one the narrative, provided by the content we see and the interactions we have online, is shaped by how we compare the behind-the-scenes versions of ourselves to everyone else’s highlights reel.

There has been some anecdotal evidence that young adults are attempting to cope with the pressures they face.

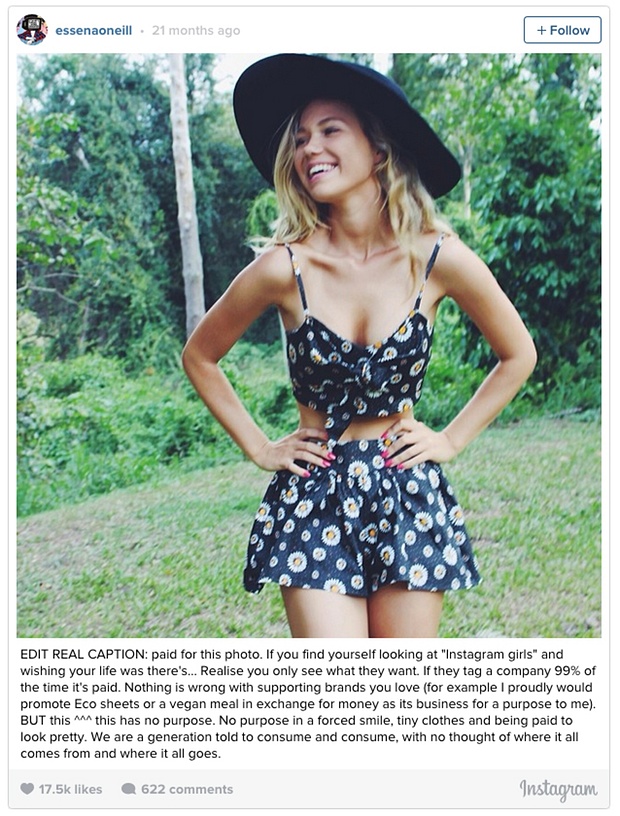

In November last year, Australian teenager Essena O’Neill quit Instagram stating it was “contrived perfection made to get attention” after she had built 612,000 Instagram followers through meticulously crafted images.

Last summer, Elle explored a trend of young school girls creating private ‘real’ accounts of themselves as a way of expressing their true identity separately from the one they cultivate online publicly.

The ramifications of this pressure became crystal clear when the media began to look into the life of late University of Pennsylvania track star Madison Holleran who leapt to her death early last year. What they found was an impeccable looking Instagram page hiding a young woman who was deeply depressed.

“In a recent survey conducted by the Girl Scouts, nearly 74 percent of girls agreed that other girls tried to make themselves look ‘cooler than they are’ on social networking sites.”

If children from age 12 are having to create a complex array of separate identities online just to survive in our digital world, reports like the one from ChildLine are going to become a depressingly common occurrence.

Our children need our help more than ever.

➤ Children are sad and lonely, helpline finds [The Times]

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.