Halsey Minor has had remarkable entrepreneurial career by any standard. He was an early business partner of Jeff Bezos; practically invented the online tech media business when he co-founded CNET in 1994, and he’s invested in and started many companies besides that.

Now, after a dark period that saw him battling the demons of depression and bankruptcy, he’s back with big plans to disrupt the banks. That’s full-circle for a man who started his career not in technology, but as a banker.

This is his story.

Dreaming of making an impact

As a high school graduate Minor dreamt of a life helping developing countries to build infrastructure like roads and dams, working with an organisation like the International Monetary Fund. With that in mind, he went to college and studied anthropology and Arabic (“in the 80s the Arab world had all the money”) at college before taking a job in corporate finance with Merril Lynch on Wall Street as a final stepping stone towards his goal, but it was there his plans changed.

“All I can say is I got very disillusioned with investment banking and it was nothing like what I was thinking about,” Minor says. “So, I immediately flipped over to my other passion, which was computers.”

Thus began a life as a full-time technology entrepreneur. But even at college, Virginia-born Minor was showing signs of his future career when he started a business called the Rental Network.

“I put three different computers around town and there was a database of apartments. You could go to, for instance, the bookstore and use a joystick and say, ‘I want a two-bedroom apartment in this part of town and I want to pay this amount of money,’ and it would spit out a list with a printer.”

It being the 1980s, these computers weren’t connected to the internet, and Minor had to manually update each computer’s database with a disk each week. He knew how the network technology emerging at the time could help but he had a choice to make. “I sincerely had to decide between (going) to Boston and trying to do this for all the university students there, or accepting the job at Merrill Lynch in corporate finance.

Despite his efforts to keep the Rental Network going in addition to his Merrill Lynch job, it died as he focused on his Wall Street career.

A young man named Jeff Bezos

After he left investment banking, Minor got back into technology, first with an early hypertext system. “I used a tool that (Microsoft co-founder) Paul Allen created called ‘Asymetrix ToolBook’, and it allowed me to build the equivalent on PCs of what HyperCard was on the Mac.”

Just as that project was coming to an end at the start of the 1990s Minor met a young Jeff Bezos, then more associated with Wall Street than the retail and technology worlds he would revolutionize a few years later with Amazon.

“We formed a partnership to launch a thing called ‘Worldwatch,’” Minor says. “That was going to take six different newsfeeds, and we were going to parse it based on content and then send it around to all the bankers based on the content. Bloomberg does that today in their sleep, so it’s not needed, but there were a couple of companies that were starting this, either to deliver a customised fax newspaper or even customised emails.

“Merrill was going to put up $750,000 to do this (but) they ended up losing a bunch of money in 1990 and they cancelled the project. So, Jeff and I were going to try to raise capital that was otherwise coming from Merrill to do this, to do this publishing thing.

“I got on the phone with Jeff and we both decided that we weren’t going to be able to raise money and this didn’t make sense and we were going to go our own ways. I was crushed.”

Building CNET

Minor might have been crushed but he managed to pick himself up and launch another startup that combined technology and publishing. CNET hit the World Wide Web in 1993. While most associate it with technology news and reviews, there was more to it than that – it was a suite of products both public-facing and behind the scenes.

“For like four years, all we did was build services that I had wanted forever, so it was very natural. CNET was just really a culmination of some skills that I had and just a passion I had for the tech industry,” says Minor.

“I had this experience doing this online publishing stuff and I was just rabid about technology press. It’s what I love, so I literally just built on the internet the company that I wanted to… I built my own product, really. Everything I built was just stuff I wanted as a consumer, so it was really easy for me.”

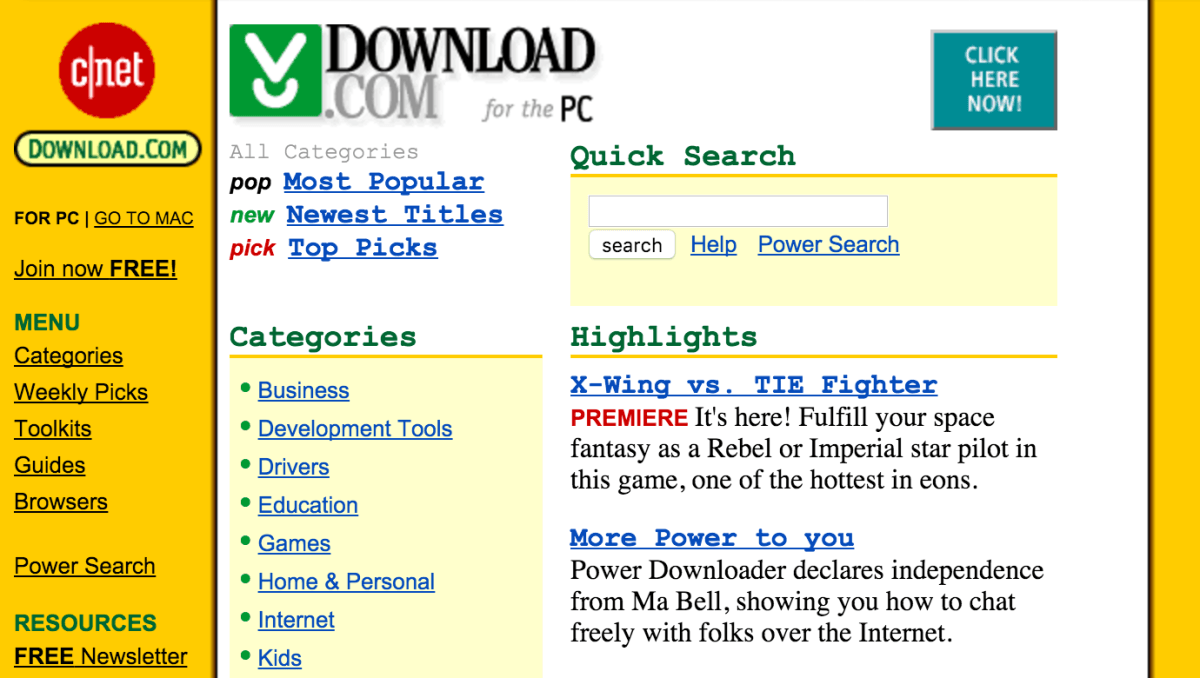

For example, Download.com launched as part of CNET in 1996. It acted as an online hub for software that was at the time more commonly given away on floppy disks and CDs stuck to the front of computer magazines, or available on disparate sites spread around the nascent Web.

While companies like Vox Media, Gawker Media and BuzzFeed are noted these days for building their own proprietary content management systems (CMS), this wasn’t just a strategic luxury in the mid-90s, it was essential. The ‘StoryServer’ CMS was spun out from CNET as a commercial product through a company called Vignette Corporation.

As a major player in online publishing, CNET contributed to shaping the online media landscape we know today. It helped launch the Internet Advertising Bureau (now the Interactive Advertising Bureau) in 1996, for one.

“I started the Internet Advertising Bureau with a reporter from PC Week,” says Minor. “We invited the internet advertising industry leaders to CNET to kick off the process. We produced five cable TV shows about technology at the time, and the idea was to be modeled on the CAB, or Cable Advertising Bureau.”

However, Minor says that after the first meeting, the problems with a publisher running such an initiative became clear. “Some people in the industry… were afraid we were going to pick up additional advertising dollars as a result of our leadership… I stepped back because the most important thing was that the IAB be formed, not that I lead it.”

Then in 1999 CNET trumpeted the “the first-ever editorial and disclosure policy to be posted on an internet media site,” ethical guidelines that made clear the distinction between commerce and editorial. While this ‘church and state’ distinction had long been established in print media, the online world was still more of a ‘wild west’ that needed to grow up as more people became active internet users.

Growing up

It wasn’t just ‘the internet’ that needed to grow up, so did attitudes to it from traditional media.

“At that point, the internet was all about being a medium and so it was the most exciting and interesting time of my life because I was… fighting for credibility of this new medium when the world at large gave us no credibility,” says Minor. “The Wall Street Journal would republish our stories and they wouldn’t even give us credit, so the passion there was really to actually allow the internet to be considered an authoritative source for content.”

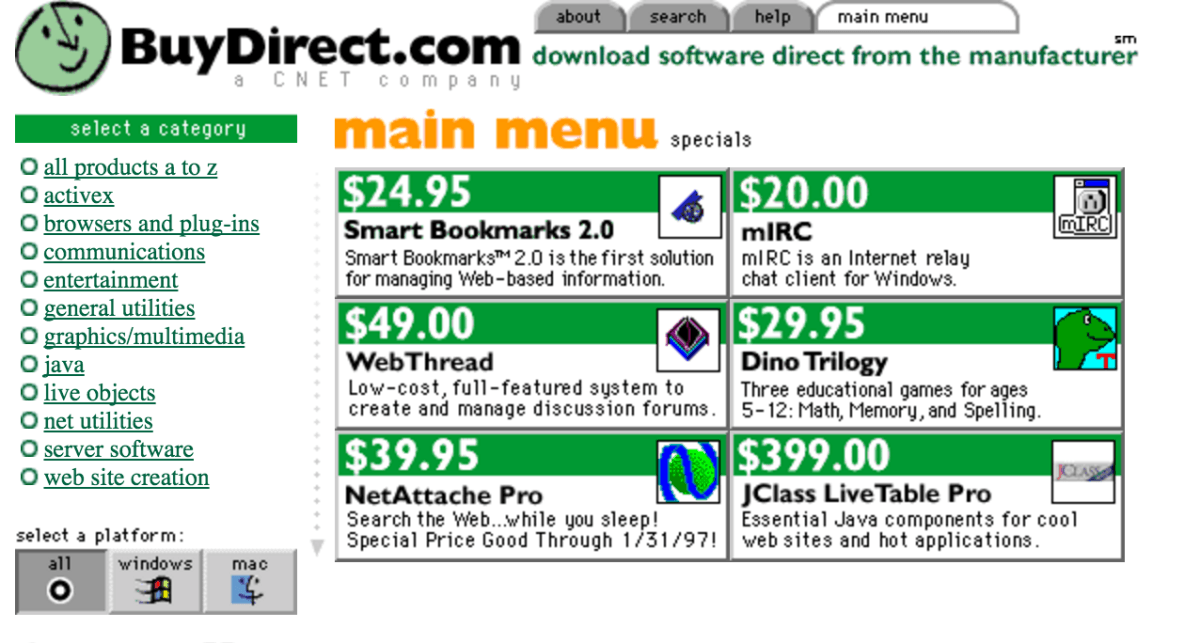

CNET acted as an incubator for other companies. Snap.com (a search portal) and BuyDirect.com (an ecommerce site) were developed in-house before being spun out. Snap became a joint venture with NBC, with the broadcaster owning 60 percent of the company, and Minor acting as CEO. At one point Snap had more traffic than CNET itself but it ultimately failed. Meanwhile, BuyDirect was acquired by another online retailer, beyond.com for $130 million in 1998.

CNET became profitable in 1998 and Minor left the company in February 2000. He’s satisfied with what he’d built. “We were a NASDAQ-100 company. We had $367 million in retained earnings and another $1.1 billion of unrealised gains from Vignette, so we had been incredibly profitable, unlike everybody else.

“That quarter we grew 130 percent year-over-year, and I literally accomplished everything I ever imagined that I could accomplish and more.”

He already knew what he wanted to focus on next.

A force to be reckoned with

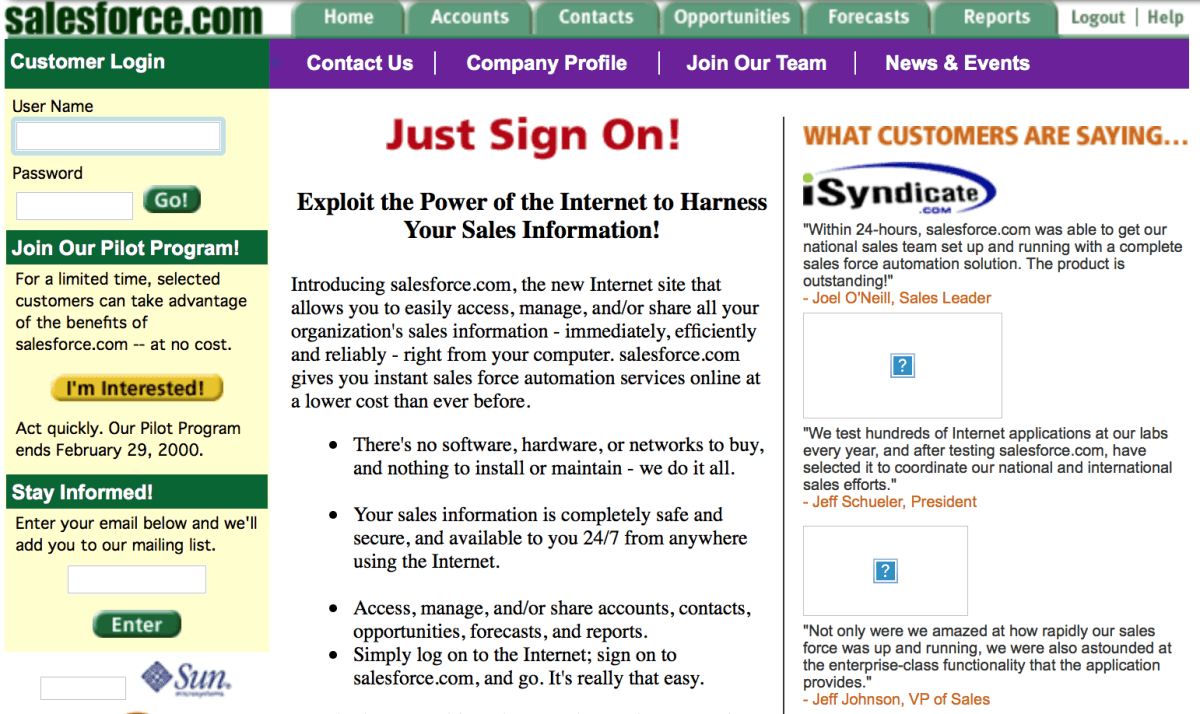

“I was the co-founder and second-largest shareholder in Salesforce, and I’d put $19.5 million into Salesforce in 1999. Marc (Benioff) wasn’t the CEO; he wasn’t the CEO until about two-and-a-half years into it. A guy named John Dillon was and so I left (CNET) to try to help build Salesforce.”

Minor is keen that history doesn’t forget John Dillon, now that Salesforce is a juggernaut intrinsically linked to the charismatic Benioff.

“Salesforce was really just a combination of me with publishing skills – Web publishing skills – and Marc with deep enterprise skills. Then John Dillon… he’s kind of been forgotten by history, but he did a phenomenal job really building Salesforce for the first two-and-a-half years.

“He was very different than Marc; Marc was kind of swimming with the dolphins and John was a submarine commander, former submarine commander, but that company went 3 million in revenue, 20 million, 50 million, while the rest of dotcom was melting down.”

After his stint with Salesforce, Minor says he retired for a couple of years but returned to the fray in July 2003 to ‘save’ a company that he’d invested in, GrandCentral.

“I was living in Virginia and the board asked me to move back to San Francisco and take over the company. No one was going to put in any additional capital, including myself, unless management was changed. Our house was on the market in San Francisco and our kids had been told that we were going to remain in Virginia.

“The company was in horrible shape with 35 people when I arrived, with everyone feuding, and I had to reduce the number of people to eight very shortly thereafter. It was a horrible experience and I promised myself I would never knowingly do a turnaround again.”

Minor’s GrandCentral was a B2B platform that focused on interoperability of applications and services. However, this wasn’t the company that GrandCentral that Google later acquired and turned into Google Voice.

“Halsey did our Series A investment as a VC,” says Craig Walker, co-founder and CEO of the ‘second’ GrandCentral. “As we were looking for names to call the company, Halsey offered to sell us ‘GrandCentral’ and the domain of www.grandcentral.com.”

The second GrandCentral was offered a service that allowed people to have one phone number, voicemail and messaging inbox linked to all their phone lines. Google acquired this company for $45 million in June 2007.

Darker times

As you might imagine, Minor had become wealthy as a result of his various business interests. Salesforce had gone public in 2004, and one year after Google bought GrandCentral, CBS bought CNET for $1.8 billion. However, Minor’s life wasn’t without its darker shades.

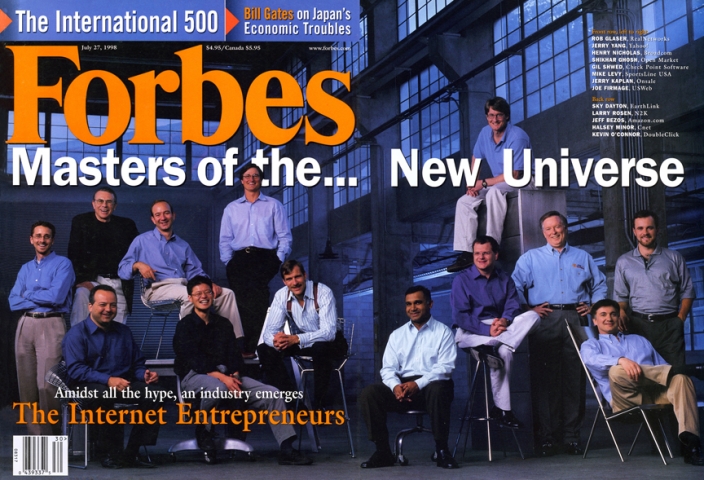

Minor says that he had never met his father. “I went looking for him in 1998, after I was on the cover of Forbes.”

He discovered that his father had killed himself 30 miles from San Francisco after battling depression, just a month after Minor had moved to the city.

The biggest setback to his career, though, followed his divorce in 2006.

“I, around 2007, went into depression and basically sort of disappeared,” he explains.

As Minor was battling a six-year period of depression, the great recession of 2008 occurred and eventually he went into personal bankruptcy. It’s a combination understandably he found difficult to deal with.

“I didn’t talk to anyone. Often, I didn’t even show up in (bankruptcy) court, because I was basically in my house all the time.”

An addiction to the finer things in life?

This silence on Minor’s part led others to fill in the gaps in the story. In May 2013, Bloomberg speculated that “a fascination with houses, hotels, horses and art” was at the root of his money problems, due to the list of extravagant assets listed in his bankruptcy filing that spring.

“That was a really easy story to write, because that’s what people want to believe. That’s not what happened,” Minor says.

“It’s a lot more complex than saying that it was fast cars, fast women, and whatever. It just wasn’t. The primary issue was that I always thought that my father – who I never met – and I were different, because I’ve always been very optimistic and very proactive and forward looking and whatever. I’ve never considered myself a depressive, but when I went through my divorce, it just upended my world.

“When people go through a divorce, it upends their world in the best of cases. Mine was followed by the complete collapse of the economy, having loans with banks, and then having to get into fights with the assets being encumbered, and all kinds of crazy stuff. I just wasn’t prepared, at that time, to be able to… I think I’m generally fairly forward-looking, and I think I’m generally a very good decision maker. I was neither forward-looking nor a decision maker during that time.

“There’s nothing that suggests that I was driving Ferraris around and building 100,000 square-foot houses; none of that was going on. The irony is, the horses that I owned actually made money. I ended up buying one horse that had a foal, that became the leading two-year-old filly in the country, and was worth $4 million, but it just all went to (the late wine entrepreneur and race horse enthusiast) Jess Jackson.”

Minor’s involvement with racehorses was celebrated in some quarters. A 2009 Horse Racing Business article supported his attempts at the time to acquire bankrupt racetrack operator Magna Entertainment Corp, stating “The racing fraternity should embrace Minor with open arms, as a force for change and experimentation – a straw that stirs the drink.”

The banking crisis, Minor says, was the catalyst for his troubles.

“The problem was, I got into a bunch of fights with banks that were, themselves, in dire straits – Merrill, and then, of course, Silverton, which was financing my hotel. They were seized by the FDIC. I’ll tell you, you don’t fight the town hall, and you don’t fight banks. That was because I basically turned my life over to lawyers.

“I’m not blaming the lawyers; I’m just saying… nobody fixes problems when they’re paid by the hour.”

Minor says that although he did own a number of houses, this was a strategy to save landmark houses from development, rather than simply owning a string of mansions for the status of it.

“Look, I’ll never be able to prove anything, because the net result was that the only way that I could move forward in my life was just to basically put everything behind me. But I think, when you look back over the long arc of my life, I think it’s going to be very clear that whatever happened, that was a very unique period. Because it’s not consistent with everything that happened before, and it certainly does not appear consistent with everything that’s happened since.’ ”

Call it a comeback

With a troubled few years behind him, Minor is back doing what he loves with two new companies, Uphold and Voxelus.

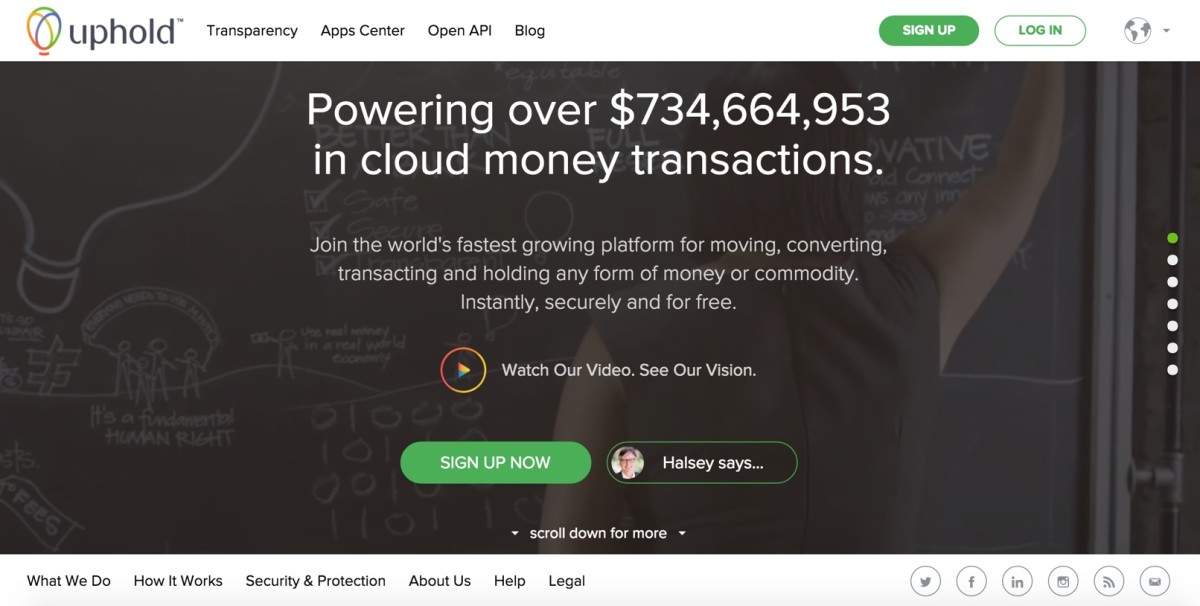

Uphold, Minor hopes, will be the future of money. After launching in 2014 as a Bitcoin-focused service called Bitreserve, it’s now relaunched, starting off by offering a free currency transfer and exchange service.

“What we’re really trying to do is create cloud-based money. In a sense, I guess you could say Bitcoin was the first cloud-based money because it’s just a bunch of servers out there that keep track of it. But the idea was to extend that concept into and make it more convenient by essentially making all currencies instant and free to exchange,” Minor says of the business where he serves as Chair and founder. Former Nike CIO Anthony Watson serves as Uphold CEO.

So, instead of transferring money from your bank account to your friend’s, you’d store your money with Uphold and then sending it to any other Uphold user is free. What’s particularly interesting here is that Uphold is entirely free to the user.

“The bet is that our costs are so low running a cloud-based money service that ultimately we can make money and be profitable, just based on reinvesting the proceeds that we’re holding.”

“It’s a very different take on… just about everybody today – PayPal, banks, etc. – they all make money on the transference of money; they make fees. They’re called payment networks. We decided you’d get a different kind of banking infrastructure where we’re free; others can charge to connect to us if they want, but ultimately our business funds itself through the reinvestment of the proceeds that we hold. We do it transparently so we don’t do stupid things, hopefully.”

“We’re a pretty radical departure from really just about everybody in FinTech, because just about everybody has a fee-based model. We’re really not trying to replace the payment networks; honestly, we’re a replacement for banks. We want you to hold your money in Uphold so that you can send it to anybody instantly, at no cost, and do free foreign exchange.”

Replacing the banks

The next stage with Uphold will be to issue debit cards, so users can spend their Uphold funds with retailers. Minor sees a future five years from now where traditional banks are taken out of the equation entirely.

“We’re actually probably more different than just about any other service in that we really are trying to create a separate monetary system that connects to all the others, but one that’s completely free, and transparent, and instant… In five years you (won’t) need to hold your money in a very expensive, physical bank someplace; you hold your money in the cloud and you use your phone to transact.”

Uphold promotional video

Storing and moving money fluidly at no cost sounds good but only if you accept one way that Uphold will be making money – investing the funds it holds.

“The big bet that we’re taking is that more and more money will come into this system that we’re building and that we will be able to invest those proceeds in liquid assets, not like banks where they go into consumer credit. We’ll never do consumer credit, but as those assets accrete over time we’ll invest them in highly liquid assets, and we’ll do it in a fully transparent way so people always know what the risk is.”

Minor says Uphold is playing it safe. “We have in reserve 102 percent of the amount of money we owe, so we’re actually over-reserved. Unlike a bank that will have 17 percent or 18 percent, we have 102 percent in liquid reserves.”

Additionally, Uphold will partner with peer-to-peer lending firms to offer low-cost consumer credit to users.

Addressing the potential criticism that this will only work well if everyone puts their money into Uphold, Minor says that he’s thinking of the service as being like Facebook – you don’t have to use it to communicate with other people online, but there are significant network effects and benefits of scale that you benefit from if you do.

Meanwhile, an API will allow others to build on top of the service. Minor says that Wells Fargo has already used it to build an app for its supply chain.

“I think (the API) is going to be of massive non-consumer use. Right now you can orchestrate the flow of goods and services, but you can’t orchestrate the flow of money, because banks don’t really have APIs that you can use,” says Minor. “So, I think we’ll become a massive tool for the ability to connect the flow of goods and services, to connect the flow of money so that you can reward people dynamically, based on the materials showing up.”

What does Minor think of taking on the banks? They’re formidable opponents, no?

“The banks, to me, of all of the competitors I’ve had – and I include the magazines and enterprise software companies and telephone companies, with Google Voice and so on – they’re sort of the least prepared to make any changes at all.

“At Salesforce, we offered small and big companies the opportunity to adopt new, more competitive infrastructure. Some companies adopted Salesforce and some still haven’t today; some still haven’t adopted the cloud model, despite how much better it is and how much cheaper it is, but I don’t see in banks, quite frankly, any interest and willingness to change.

“You see people making these statements, like Jamie Dimon, like, ‘Our ‘Uber moment’ is upon us,’ but I don’t really think that any of them are really taking it seriously. I think it’s only when the banks actually start seeing it show up in their own financial numbers, or any business when they actually start seeing it happen where they can directly attributable a fall in their profitability to the rise in somebody else’s, it’s only then when people start taking it seriously.

“The difference between the banks and everybody else is when I started CNET there were 300,000 people on the Internet. I could only grow as fast as the Internet could grow, so the magazines had, quite frankly, a very long time to adapt. They didn’t, but they had a very long time to adapt if they had wanted to. Actually, (US publisher) Ziff Davis did fairly well because we ended up buying ZDNet, even though the magazines ended up going bankrupt several times.

“We have 3 billion people on the Internet today, roughly, give or take a few hundred million. All of these people have seen time and time again that whatever is new has brought real consumer benefit, so people are much more down with trying something new now than they were when I was launching CNET and everything was new and nothing was proven.

“So, now the new is always equated with positive attributes as a consumer, and there are 3 billion of them ready to change. So, I think banks going last is going to be the worst possible position because people are prepared to make changes, and you’ve got 3 billion of them that can do it relatively rapidly.”

“I think other than banks making statements and saying, ‘We’re doing blockchain stuff,’ which, as you and I know, doesn’t really mean anything… other than some very broad statements and partnerships and think tanks and whatever, I don’t see people preparing their infrastructure and figuring out how they’re going to… dramatically cut their internal costs to match people like me, who are running everything out of the cloud, running on Amazon Web Services, without big branches or mainframe computers.”

Tackling virtual reality

Aside from Uphold, Minor’s other current project is Voxelus, a platform that aims to democratize VR content creation.

“The idea is to allow people to be able to create – not too dissimilar from the way Minecraft operates – but allow people to be able to build their own experiences. And we’re already multiplayer so you can jump in. Unlike Minecraft, there’s not a single aesthetic that you have to sign up for,” he says.

Voxelus demo video

As well as individuals, the platform will cater to businesses that want to create branded VR experiences. As of this March, a marketplace will allow users to sell their creations to others.

“The goal there is to do what YouTube did over a very long period of time, which is to create an ecosystem that allows people to get paid for their work. What I wanted to do is I just wanted to accelerate it.”

Minor sees Uphold and Voxelus as complementary businesses and the two are tied together by the idea of cloud-based currency.

“As it turned out, the whole concept of virtual currencies came out of gaming. (Now shuttered Bitcoin exchange) Mt. Gox was originally an exchange for Magic: The Gathering players, so the whole notion of virtual currency basically was created because a lot of big games have their own internal currency.

Voxelus has an internal currently called the voxel, which is a fork of Litecoin.

“I can give the voxel all these capabilities, like easy to buy with dollars, euros, and credit cards, etc. on Uphold, so it’s sort of a combination of the business model of both companies,” says Minor. “We’ll see how it goes, but I’m fairly bullish right now that I don’t see any reason why it shouldn’t work.”

The concept of a VR platform backed up by a virtual currency sounds very similar to Linden Lab’s forthcoming Project Sansar. Linden Lab has made a huge success of the economy in Second Life, so there’s precedent for what Voxelus is looking to achieve.

Minor isn’t familiar with Project Sansar, “but I think there is a broader movement going on, which is people not just as players of games but people being able to add their own creative touches to the worlds that they are involved in and participating in. I think that’s where most of the growth is going to be, particularly with VR.”

On the up

After having had extreme success followed by a significant low patch, Minor has emerged from it with a philosophical viewpoint and come to terms with his father’s suicide.

“I always had a great deal of resentment for what (my father) did. Having gone through depression myself, I developed a lot more compassion for him, and I developed, quite frankly, a lot more compassion for myself. These things, you never sign up for them, but I have to tell you, I’m a stronger person as a result of everything that’s happened.

“I’ve delivered, I think, an incredible lesson to my children that when things don’t go your way – which sometimes they don’t; sometimes they go disastrously wrong – you still get right back up again and you do it again. Quite frankly, I hope, when all is said and done, that this is instructive for other people who’ve been through similar experiences to know that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

“You can get past this and you can go on and be every bit as successful as you were before, and hopefully, in my case, even more so.”

___

This piece was edited shortly after publication to clarify details around the story of GrandCentral.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.