Twitter needs no introduction these days – TV and radio shows seem to mention it all the time, meaning that even the least tech-savvy of people have a basic idea of what it is and how it works. However, yesterday showed that we’re still learning the boundaries of how it’s acceptable to use tweets.

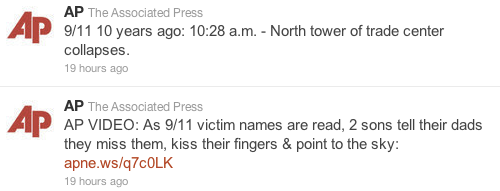

Yesterday’s tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks saw a number of news organisations recounting the events of that day in 2001 on Twitter as a real-time list of events. The AP and The Daily were two of those, mixing details from the day of the attacks with coverage of the ten year memorial ceremony.

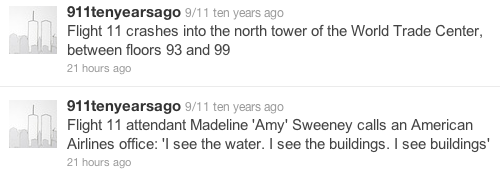

Meanwhile, The Guardian chose to open up a separate Twitter account, @911tenyearsago, solely to retell the events as they happened.

Both approaches were similar, however The Guardian’s received such a backlash that it was forced to stop tweeting its updates early.

The Daily (with 95,5000 Twitter followers) and the AP (with 509.500 followers) continued their tweets of the events from ten years ago right up to the collapse of the second tower of the World Trade Center. Meanwhile, the Guardian’s dedicated feed, with just 3,800 followers, was forced to abandon its retelling early.

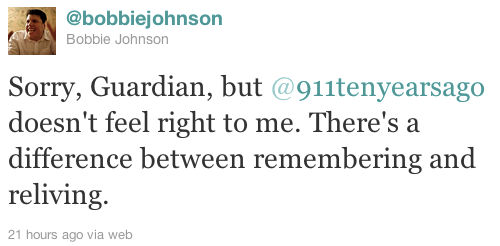

So, why was The Guardian’s approach – a dedicated account, separate from its main feed, so offensive to some? It’s fair to say that the details on its feed were more graphic than those given by the other news organisations, but if we’d seen those same details listed in a newspaper or a history book it wouldn’t have been seen as a problem. And it’s fair to say that a separate feed for the retelling meant that you only needed to follow it if you really wanted to.

Iain Hepburn summarised the problem with the Guardian’s tweets well in a blog post yesterday (emphasis mine):

Retweeting events as facts, as if they were happening now, strips that emotion and context away, boiling them down into just 140 character statements. We lack neither the immediacy of the events happening now, nor the distance of – say – the World War 2 tweets in a similar vein put out by the National Archive.

Had they been providing context to the events – linking to the stories of loved ones, survivors and families of the victims – there may even, just, have been a narrow justification to it. But the Guardian failed to do that. There was no humanising of the event, just a stark publishing of facts which weren’t new or particularly unknown.

The 16 tweets issued by the Guardian’s account didn’t add anything to the coverage. It was just a reiteration of events, an attempt to liveblog something that wasn’t live. It was a redundant exercise – and one that smacked of astonishingly poor judgment by whoever gave it the go-ahead.

In defence of the Guardian, it sounded like an interesting idea to me at first. It wasn’t until I saw the tweets – recounting one of the most traumatic events of recent history in real-time – appear in my Twitter feed amongst people’s memories of the day and coverage of the memorial ceremony, that it started to look out of place.

They were just tweets containing facts, like millions of others published every day, but the way they appeared on that day, in that context, made them feel wrong. It’s interesting to compare them with Jeff Jarvis’ tweeted personal recollections from the day – they too, were a list of facts (this time in the form of memories) but they came across completely differently as they had an emotional undercurrent running through them.

The Guardian may have made a mistake yesterday, but it shows that we’re still discovering all the nuances in context and timing that can affect the way we ‘read’ Twitter.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.