This is the first in our Future Of series, where we analyze and dissect one facet of life that’s been impacted by digital technology. Today, we look at libraries.

“You have no idea how eager I am to ensure that the notion of ‘library’ does not disappear – it’s too important.”

– Vint Cerf, 2013

Vint Cerf is considered a founding father of the Internet. He was involved in a project that saw the first ever message sent from one computer to another on the ARPANET, a predecessor to the Internet, back in 1969, before he received his doctorate from UCLA. Today, Cerf is VP and Chief Internet Evangelist for a rather large online company you may have heard of – Google.

As with many traditional industries, Google has had an immeasurable impact on how people access information. So when journalism professor Jeff Jarvis asked Cerf what he saw as the future of libraries , his expressions of “deep concern” about the way information will be stored and passed through generations perhaps held more resonance than most.

But what does the future hold for libraries? And more specifically, how can we control and manage the staggering amount of data that’s processed each day online and through other digital forms?

We take a look.

The future of libraries

According to Lionel Casson, author of Libraries in the Ancient World, libraries are thought to date back as far as 2300 BC.

“Archeologists frequently find clay tablets in batches, sometimes batches big enough to number in the thousands. The batches consist for the most part of documents [such as] bills, deliveries, receipts, inventories, loans, marriages contracts, divorce settlements, court judgements and so on.”

Some also contained literature, writing exercises, hymns and other texts we’d perhaps more closely associate with the modern concept of a library.

To you and me, a library probably means a bricks-and-mortar building filled with paper books that anyone can access. But at a more abstract level, it’s really just a repository of information – this could be books, CDs, DVDs, journals and everything in between. And it doesn’t even have to be a physical entity either.

Like it or not, Wikipedia is a library. Think back to the pre-Internet days – where would you go to find out what movies Laurel & Hardy starred in together? Or gen up on Neoclassical architecture? Chances are you’d buy a new book, peruse a second-hand bookstore or, indeed, visit the library. Now, you’d likely plug a few search terms into Google and click one of the first links that come up on the subject – and there’s a good chance your path to knowledge would start with Wikipedia.

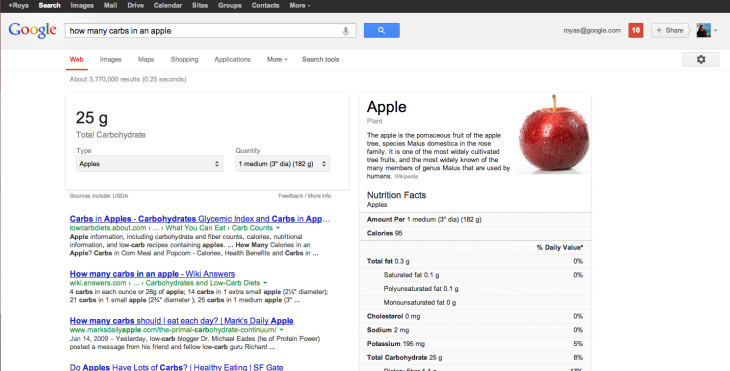

Heck, despite Google’s claims that it’s not the Internet, it pretty much is in many people’s eyes. The Internet is like one giant library, and Google taps this information to display key information directly within its search results. Want to know how many calories are in a banana? Google’s Knowledge Graph will tell you.

And what about your own portable library that sits on your Kindle, Kobo or Nook e-reader? Your physical bookshelves at home may be filled to the brim, but is there much on there dated post-2010? That’s not a rhetorical question by the way, leave your response in the comments at the bottom.

There’s little doubt that the library of the future is ‘digital’ – while that’s not a problem per se, there are issues that must be addressed.

Bit rot

“I am really worried right now, about the possibility of saving ‘bits’ but losing their meaning and ending up with bit-rot,” said Vint Cerf. When he previously said he had “deep concerns”, this is chiefly what he was referring to.

“This means, you have a bag of bits that you saved for a thousand years, but you don’t know what they mean, because the software that was needed to interpret them is no longer available, or it’s no longer executable, or you just don’t have a platform that will run it. This is a serious, serious problem and we have to solve that.”

With physical books, there are some problems – fires are particularly hazardous, while language issues have made some older texts tricky to decipher. But as we saw with the Rosetta Stone, humans get there in the end.

The relatively recent introduction and popularization of digitized media means that we should be looking at how this information will be stored and protected for posterity. Not just one or two generations, but thousands of years.

Consider all those floppy disks from school and college that are pretty much redundant now? They’re not entirely inaccessible, but it’s unlikely you’d be able to access that old essay you wrote at the drop of a hat. Now, amplify that scenario over tens, or hundreds of years and it’s evident there is a genuine risk of losing a lot of information with the introduction of new formats and storage devices.

According to Cerf, this will require a whole new infrastructure that has yet to be invented:

“We have to retain this notion of a place where information is accumulated and kept and curated and managed. So for some people, who imagine ‘Well, it’s all digital, and all we have to do is run the Google index’, I don’t think that’s exactly right.

I think there’s a whole infrastructure that has to be not only created, but invented and sustained in order to make sure the knowledge that we’ve been digitizing is retained and reusable over a long period of time. Otherwise, we’ll have denied ourselves what is the most important potential I can think of – to have all the knowledge of human-kind at our fingertips.”

So with Wikipedia effectively killing off the 244-year-old Britannica Encyclopedia, we find ourselves in a position where we must design, develop and maintain a system that will survive the foggy ruins of time.

What might the libraries of the future look like?

I don’t know about you, but I can’t remember the last time I set foot in a public library. Actually that’s a lie – the last time I set foot in a library was in 2010, when I moved into a new home and my broadband wasn’t set up yet. My local library offers Internet, so I spent a whole week camped up, gratefully receiving the free WiFi. It was either that, or McDonald’s.

Before that though, I don’t think I’d set foot in a library since the late 1990s. Libraries are important parts of the community though – it’s not just about reading a book for free. Not everybody can afford a laptop and home Internet, so by offering additional services gratis to members, libraries are trying to remain relevant within the digital age.

Whether this will remain the case five or ten years from now, remains to be seen. Governments and local authorities around the world will continue to look for ways to cut costs, and if they see that x% of the community now have fiber broadband at home, the axe might just be dropped on all those lovely book repositories.

So what might a library of the future look like? The best way to get an idea is to look at some of the endeavors going on at present.

Google recently revealed it was providing “design know-how” to the architects hired by Future Library, an initiative that’s striving to transform Greece’s public libraries into “media labs and hubs of creativity, innovation and learning”. The aim is to attract segments of society who spend little time there – entrepreneurs, students, unemployed, and immigrants.

In many ways, Greece is as good a place as any for such a project – while the Library of Alexandria was opened in Egypt round about the fourth century BC, many of its books actually came from pilgrimages to the book fairs of Rhodes and Athens in Greece.

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation is pumping €560m to build a Cultural Center, which will play host to the National Library of Greece and the Greek National Opera. Feeding into this is the Future Library, and Google’s role will be to “review the architect submissions, provide technical comment on all proposals and assist the Foundation” towards making the project a reality.

“Some might have imagined that the Internet would make libraries superfluous or irrelevant,” says Dionisis Kolokotsas, Public Policy & Government Relations Manager, Greece. “But the reality looks like quite the opposite – the Internet can help libraries become a center for new digital learning and a point of reference for local communities.”

Of course, a big part of this will be to promote Google products among librarians – including Search, Google+, YouTube and more. But that’s to be expected, right?

In November last year, the Future Library hosted a so-called ‘Un-Conference’ about the library of the future, which engaged some 6,000 kids, parents and other professionals from across Greece, consisting of 98 events in 8 libraries in Central Macedonia. You can view a snapshot of the initiative here.

On the surface at least, it seems like the writing is very much on the wall for physical bricks-and-mortar libraries, but there is a clear and tangible desire to preserve this traditional hub of learning. But as we’re seeing in Greece, we must recognize the need to evolve these age-old institutions.

We could do worse than take a cue from the Hunt Library at North Carolina’s State University, which features around 100 group study rooms and technology-equipped spaces to aid learning, research, and collaboration.

Not only is it a visually-striking space, but it has quirkiness galore, including a robot-driven bookBot – an automated book-delivery system that holds up to 2 million volumes in one-ninth of the space of conventional shelving.

The bookBot is 50 feet-wide by 160-feet long by 50-feet tall, and it delivers books in minutes through requests placed in the libraries’ online catalog. You can actually watch the bookBot in action through a glass wall on the first floor – Robot Alley – as four robots stomp along huge aisles to retrieve materials.

It also houses video games and a 3D printing lab. The beauty? It’s open to everyone, and was funded through the public purse. The desire is there for libraries, what’s needed though is innovation.

Over in San Antonio, the soon-to-launch BiblioTech is seeking to use technology to “remove barriers to library access, enhance education and literacy and promote reading as recreation.” What’s different about this library? Well, there’s not a book in sight.

By all accounts, Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff was inspired to drive the project forward after reading Walter Issacson’s biography on Steve Jobs. Indeed, rather than aisle-upon-aisle of dusty books, there will be e-readers to share, computer terminals, laptops and tablets.

At Harvard, a temporary pop-up Labrary space was previously set up in the middle of Harvard Square, serving to prototype new library ideas, bringing together librarians, students, faculty and members of the wider community.

In England, the Arts Council is diving deep into Envisioning the library of the future, a research project designed to help it understand, well, the future for libraries and what can be done to develop them for a digital future – part of this included a review of future trends.

Even airports are getting involved.

“When Kansas State Librarian Joanne Budler — Library Journal’s 2013 Librarian of the Year — looked around at passengers waiting at a baggage claim a few years ago, what she saw were readers,” writes Ian Chant in the Library Journal. “Or potential readers, at least. The waiting passengers were nearly all focused on their phones. Budler was working out how she could shift that focus from a phone to a book when she realized it might not be a shift, but a combination.”

The resulting Books on the Fly campaign, which kicked off initially at Manhattan Regional Airport, involves the public scanning a QR code which are placed on cards sporadically throughout the airport. This then sends the user to the Kansas State Library’s eLending service. Non-members are redirected to Project Gutenberg’s mobile-optimized site, where they are invited to download books that have passed into the public domain.

These are just some of the initiatives currently underway that involve libraries around the world. We’re very much in a transition period – it’s clear the desire to preserve the library concept is there. Whether 10, 20 or 100 years from now that means completely paperless reading areas, involving touchscreen information portals and robotic assistants as guides, remains to be seen.

The bigger picture

The broader question here perhaps isn’t libraries, but education on the whole. We’ve previously looked at the future of learning in a networked society, which draws on some of the leading minds in education and technology.

“We’re probably at the death of education, right now,” said Stephen Heppell, a Professor at Bournemouth University, who’s regarded as one of the most influential academics in educational technology. “I think the structures and strictures of school, learning from 9 until 3, working on your own…not working with others…I think that’s dead or dying. And I think that learning is just beginning.”

So…how is technology changing the process of learning, exactly? “There’s a very big difference between ‘access to information’, and ‘school’,” said Seth Godin, entrepreneur, author and public figure. “They used to be the same thing. Information is there online, to any one of the billion people who has access to the Internet. So what that means, is if we give access to a 4-year-old, or an 8-year-old or a 12-year-old, they will get the information if they want it.”

If you’ve yet to watch it, this 20-minute video is well worth your time:

Feature Image Credit – Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.