This isn’t just a story about the future according to Josh Harris. This is a story about Josh Harris according to Josh Harris. When I was first introduced to the Internet entrepreneur, I scheduled our interview for 2pm on a Friday afternoon at the offices of Morris & King on 5th Avenue. After I watched We Live in Public, a documentary about his life, I emailed him and changed it to the following Tuesday at 5pm, when I knew I wouldn’t have to worry about getting back to my desk. Everything you are about to read was told to me in 5 hours, over 2 beers and a soggy cigar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Only one alarm was set off in the process.

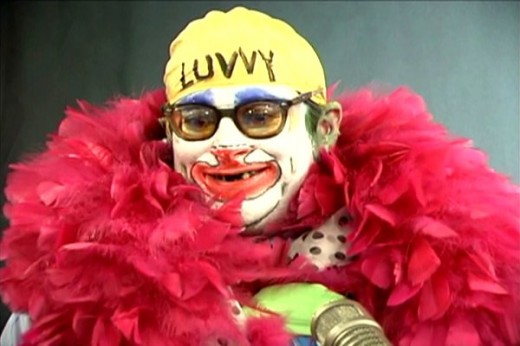

In the late 90s, Harris was a bona fide New York City business star when his company, Jupiter Communications, went public. There was a day when he had a liquid net worth of $40 million. During that time, he also ran a second Internet company called Pseudo Programs, Inc., which was an Internet television network. While running Pseudo, he dressed like a clown named Luvvy and began throwing decadent parties at his SoHo loft and running Manhattan’s underground art scene.

In March 2000, he rented a helicopter and flew around the World Trade Center filming an art group called “Gelatin” removing a window from the 91st floor, sliding a balcony through the slot, and one by one each man nakedly stepping out onto air. Harris believes the U.S. Government has been watching him ever since. A decade later, he was the subject of the Grand Jury Prize winning documentary film “We Live In Public” at the 2009 Sundance Film Festival. A year later, he made it into the Museum of Modern Art. In his spare time, the self-proclaimed ‘Ethiopian national’ is an artist, a sports fisherman, a poker player, an apple farmer and he once shot three turkeys dead with one round.

“He is one of the 10 most important people in the history of the Internet,” said entrepreneur Jason Calacanis, who chronicled New York’s tech scene in his publication, The Silicon Alley Reporter.

Joshua M. Harris was born in Ventura, California, the youngest of seven children. His father, a CIA agent, was hardly ever home. His mother, a social worker in California, had little energy left for her own children after a long day working. He grew up watching television for hours on end. In an interview with Errol Morris, he said, “His only friend was the tube.”

Gilligan’s Island

In his days running Pseudo, Harris often dressed as “Luvvy,” his alter ego, a scary clown in smeared makeup based on the wife of Thurston J. Howell III, a character from Gilligan’s Island, a show he describes as “his real family”. The word luvvy literally means a person who is involved in the acting profession or the theater.

The influence of Gilligan’s Island and a TV-upbringing hardwired Harris into a man obsessed by interactive entertainment.

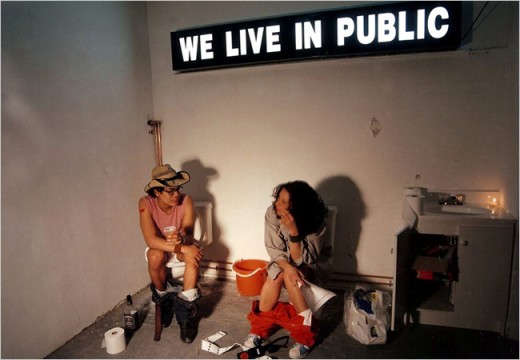

QUIET: We Live in Public

QUIET was Harris’ heady social experiment, which became a major part of the eponymous Sundance Film. For the experiment, Harris enlisted 150 participants to live communally in a 3-floor bunker at 353 Broadway at the end of 1999. The entire bunker, complete with a mess hall, a see-through shower and a firing range was wired with webcams. Anyone in the central control booth of the bunker could watch anyone else as they ate, slept, made art, fought, fucked, etc. The bunker was raided by city authorities on the morning of Jan. 1, 2000. It had descended into chaos, and everyone was evicted. The final night of QUIET was compared by the MoMA to Truman Capote’s “Black and White Party” as one of the two best parties conducted in the twentieth century. The film “We Live In Public” was purchased by the MoMA for its permanent collection a year after its release in 2010.

During this time, Harris met a woman named Tanya Corrin, whom he refers to as his “fake girlfriend”. By then he had wired his SoHo loft with over 30 cameras including the toilet, the closet and the refrigerator. According to Harris, he cast her as his girlfriend to live in his home under constant public surveillance. According to Corrin, they were very much in love. After a few months of living together under the public’s eye, Harris “lost his mind” and the two split and have barely spoken since.

Some say he “invented reality TV”, but shows like MTV’s ‘The Real World’ were also broadcasting at this time. What Harris conceptualized was the emergence of all-encompassing public interactions online, almost a decade before the time of Chatroulette, YouTube and Facebook.

Harris left New York City and moved to upstate New York where he operated a commercial apple farm named Livingston Orchards, LLC. “It only took me 5 months alone on the farm to get my sanity back,” he says. “The first two were like coming off a heroin addiction just watching my apple trees grow. A key epiphany? I know how to wire a farm.” Later that year, in 2001, Harris received word that Jupiter’s stock had tanked, and he went from being worth $20 million to $2 million in one phone call.

Three weeks before that fateful day in September, 2011, The New York Times ran a story titled, “Balcony Scene (Or Unseen) Atop the World; Episode at Trade Center Assumes Mythic Qualities.” The author wrote about an event that took place on a Sunday morning in March 2000, when a balcony was allegedly installed and, 19 minutes later, dismantled on the 91st floor of the World Trade Center by a group of Vienna-based artists known collectively as Gelitin. I’ve copied excerpts from the article below detailing the affair, which has “taken on the outlines of an urban myth, mutated by rumors and denials among the downtown cognoscenti.”

Ali Janka, a member of Gelitin was quoted in the article as follows: ”If you write about the balcony, maybe you can just not write about it too much.” The author writes that he made several calls protesting the appearance of an article, despite the fact that the artists had published the book. In the article, Harris explained that Leo Koenig, the 24-year-old art dealer who represents Gelitin, got him involved.

The night before…, Mr. Harris said, he rented a top-floor suite at the Millennium Hilton, across the street from the Gelitin studio, and invited people to what guests described as a night of decadence. Near dawn, he and several others took cameras and boarded a helicopter, communicating with Gelitin via cell phone…

Mr. Koenig now says the balcony never happened and, at any rate, he didn’t see it. The book, which costs $35 and was printed in a run of 1,200 copies, is meant to provoke questions about its veracity, he said.

At the suggestion that the project might have been faked, Mr. Harris seemed almost offended. He produced March 2000 credit card bills bearing charges of $2,167.44 from the Millennium Hilton and $1,625 from Helicopter Flight Service.

At about the same time that Mr. Harris was digging up proof, Gelitin was removing almost every trace of it from their Web site.

This artistic act of subversion may have cost Josh Harris his freedom, leading him to believe that ever since the Twin Towers were brought down, the U.S. Government has been watching him.

By the time the 2nd tower fell, Harris claims a guy named Jerry, the former Head of the Forest Rangers, who had also worked for the FBI, showed up to buy apples. They went turkey hunting and Harris impressed Jerry with his 3 turkey takedown. At this point, you must be wondering is the son of a Cold War CIA agent simply programmed to be paranoid?

In 2005, Harris put his farm up for sale and a man named Robert Rosen, a former New York State Navy Admiral, offered to buy it. Negotiations were painfully slow so Harris flew off to Panama for a month to shoot a film. He says just before the gate closed on his flight out, a catatonic guy who looked like he’d taken too many Xanax sat down next to him. One month later, just before the gate closed on his flight back to the States, that same man sat down next to him, steadfast and sober. The day of the closing comes. It’s a public closing in New York State. Harris is there, his brokers are there, the title insurance reps, secretaries and Harris’ lawyer. Just as Rosen signs the paper, he looks up at Harris and says:

“Wherever you go, whatever you do, we’ll be watching you.”

“There’s been only two times in my life when my knees buckled,” explains Harris. “At that moment, and the first time I joined the mile high club.”

The first thing out of his attorney’s mouth was, “They’re going to get your money.” Harris took it to heart, and said, “If they’re going to get my money, then I’m going to get my freedom.”

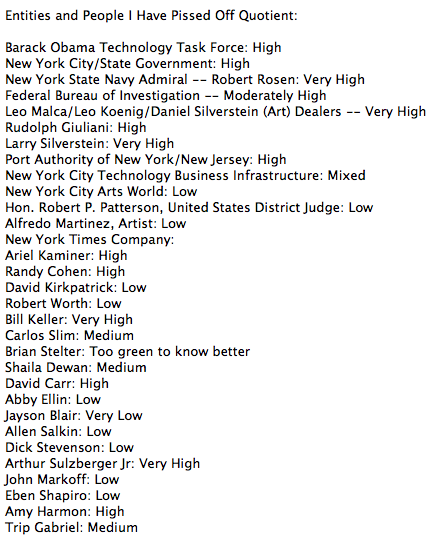

Harris has pissed off quite a few people in his life. In fact he made a list and published it on Facebook:

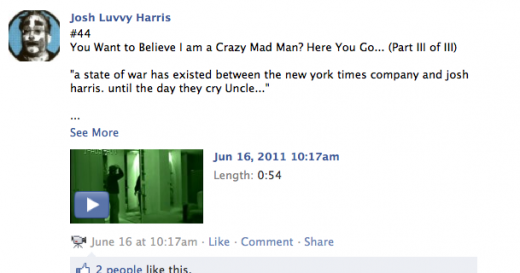

Also on Facebook, he’s publicly declared war against The New York Times, and continues his case in a series of 46 installments on his Facebook wall. Harris is certain the federal government has read them. For each installment, Harris writes, “a state of war has existed between the new york times company and josh harris. until the day they cry Uncle…”. Why did they wait over a year to publish the story about Gelatin and Harris’ helicopter escapade? Were they setting him up? If so, who was behind it? The conspiracy theories are provoking to say the least.

In 2007, Harris spent the last of his fortune in Hollywood on another interactive television venture, Operator 11, which he said “worked great but ran out of money (mine).” Afterwards, he moved to Ethiopia, chilled out, smoked pot and he says, got his mojo back. “It’s the one place in the world I feel at home,” he says of the country he also lived in as a child.

From 2009-2010, he earned a living playing poker, crashing in Jason Calacanis’ pool house and riding around in his yellow Corvette. For the past year and a half, Harris, now living in an artist’s space in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, has been hanging out with artists, the kind of people who would “give you $10 if it’s all they had.” He’s been living a fairly healthy life, without stressing too much. He eats the same thing every day because he’s training for his next project. He blends grapefruit juice, apple, carrots, banana, and wheat germ for breakfast, then has a Bento box later in the day. He lives with two Australian artists in a loft on Berry St. in Brooklyn. He’ll have to find a new home in just two weeks.

Harris’ art in Williamsburg, Brooklyn:

The Future according to Josh Harris

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players…

-Shakespeare, As You Like It

Harris believes his ability to predict the future is simply preternatural. He says “the Singularities” visited him in 1992 and gave him the idea for a short animated video titled “Launder My Head” with lyrics like “come form with us to conform with us,” in other words, the Singularities are coming and this is how it’s going down.

It’s been less than a year since a man named Josh Harris emerged back on the scene in New York and this time he’s raising funding for The Wired City, a crowdsourced Internet TV station where all the viewers are also the broadcasters, multicasting to each other and the World Wide Web. Harris has put his project on Kickstarter, hoping to raise $25,000. With 12 days left, he still needs $20,683 to raise the $25k to fund the project.

“The Wired City cyber-ship sound stage includes a capsule hotel (submarine style sleeping quarters), mess hall, bathrooms and a Star Trek/NASA bridge: everything is wired. On set you will sleep in a capsule hotel, eat in the mess hall, and use the facilities but most of the time you will be communicating (via net bandstands) with citizens who are at home.

On set we group people into twenty person “net bandstands” (workstations) each of which has a conductor who then reports to The Wired City bridge (think Star Trek). Citizens at home follow suit by netcasting from their “home netcasting studios” using common physical backdrops, uniforms, electronics and video formatting. Citizens earn their way onto the Wired City cyber-stage by doing something special (saved the world, won a contest, built an audience or are on a mission).”

According to Harris, The Wired City is an experiment of what the future will be like. If you understand the future of toothpaste you can understand how The Singularities will occur in our lives. In The Wired City, it will be simple for Harris to get 10,000 people to hold up a tube of Crest and get Crest to sponsor him. How do you organize 10,000 people into such a cacophony? The motivation will be gaming points.

“Before you were born,” he says, “There was no such thing as a home theater. 20 years ago, it was bulky, awkward and geeky. Now there’s a home theater on your phone. Today the new concept is a home studio and the idea that the home is a soundstage. Just as we have desktop or mobile top [he points to his phone], the entire home is going to become a soundstage. There will be sensors and monitors on your bath top, your kitchen top, everything, just like We Live in Public.”

For brands like Crest, the wiring in our homes will herald the next golden age of advertising. The very moment you brush your teeth at 8:32 on a Monday morning, you’ll be with 20 other people who are also brushing their teeth, they are your virtual friends. Celebrity endorsements will work beautifully here. Imagine how many more men would tune in every day if they knew they could brush their teeth with Cindy Crawford? Your day will be broken up into micro parts and brands like Crest will be amplifying the formerly mundane moments in your life. From a business perspective, Crest’s job is to own the bath top and not Colgate. Your bath top will be wired with oral hygiene monitoring in the form of a device or sensor that can detect Gingivitis or a cavity. When the device is set off, voilá! A dental hygienist is on the scene. And if it works for Crest, it will work for shampoo, cosmetic brands, meals around microwaveable dinners, etc.

Harrowing? Yes. But far-fetched? No. A new startup in New York City just launched: Consmr, an app that lets you “check-in” to consumer packaged goods.

What drove Harris crazy when he lived in a Truman Show like reality with his “fake girlfriend”, other than losing his fortune, was when people online, his followers, started to get into his head and he was barely able to make a decision at any moment. Harris says that scenario was like a caveman version of what’s to come. With your day split into microparts, you will suffer from a psychic fracture. The issue won’t be about maintaining privacy. Your privacy will be long gone. The issue will be when your brain overloads, what in computer terms happens when the CPU goes into complete multi-tasking mode. And this is how we will enter the hive, also known as the Matrix. And that’s Harris’ Singularity. It’s just a matter of time, he says.

“This is how you have to look at it. I try not to make judgements, it’s just a natural evolutionary process. I don’t know how they knew it but The Mayans were right: 2012 is the end of the world. The world isn’t going to blow up. But 2012 is the year when the Singularity’s effects will start to take place. When our lives become a collection of micro day parts. Unlike Isaac Asimov, who said his biggest regret is that he wouldn’t be alive for The Singularity, we actually are going to be present at the shift. It’ll start next year. It’ll seem like magic, just like television was magic, radio was magic, the telegraph was magic, and maybe even smoke signals were in their day. This is going to be real magic and we’re going to be alive to witness it.”

As time goes by, notice how expensive physicality becomes as opposed to virtual space. We will start to operate more and more in the virtual space. True, we lose a little in the translation but it doesn’t stop it from happening. 10 years ago, my job as a reporter for The Next Web wouldn’t have existed. Now every day, I hang out with my coworkers in a virtual world all day long.

Harris says the golden age of Silicon Valley is now at the beginning of its decline. The age of utilitarianism has reached its peak and the age of programming is now back. They’ve worked themselves out of a job. Technologically speaking, the underbelly of everything is mature enough. We have the code. How do you capture the bathtop? The desktop? How do you market and how do you change people’s minds? That’s not what Silicon Valley does well. The best people suited to run the future will be Madison Avenue and Hollywood.

Harris imagines a future, where instead of presenting a will where our surviving family members are given money, they will be handed the data of our lives. DNA will no longer be biological, it will be virtual and it will be something you can package on Wall Street.

This is the darkness before the dawn. The magic of the movies is gone, it’s been completely commodified. A movie is now just an expensive 90 minute file. Even music albums don’t make sense anymore. Why would you pay a dollar for a 3 minute audio file when you can can get it on YouTube for free?

‘”If I was 14-years old today, I wouldn’t be in a music band, I’d be in a net band. I don’t know what they’d make but that’s why I’m creating this platform. I’m curious what the 14-year olds will do. The garage full of instruments, the turntables – they’ve been replaced by a mini network operations center. 10 years from now, when you go to see a net band perform at a venue, you’ll already know everyone there through virtual relationships in a home studio environment. You know what their PJs look like and how they pick their nose. But it’s still important to physically meet in the future to really mesh together. Everyone shares a moment and the band somehow ensconces themselves in your life. When the net band is on stage, everyone is jacked in, whether it’s through a phone, laptop, or whatever the device du jour.”

People in the 60s at Woodstock had to take drugs before they could commune with each other, because drugs and alcohol reduce the social inhibitions allowing them to experience love and each other. In the future, you won’t need to take drugs. You’ll already know everyone so intimately that you don’t need the ‘knock me out’ types of drugs as a catalyst.

When asked why people would want to brush their teeth together, eat together and poop together virtually, he replied, “You just have to get over those sociological barriers and advertisers can convince you it’s just not a big deal. The one thing I’m very sure of is that people can be convinced of anything if you find the right gratification schedule.”

“When you can get 200,000 people in one day generating content, you can compress the love, the kids, the deaths, the tears into an hour. In my experiments, I had attempted suicides, domestic violence and even one goth guy who wanted to join so bad he stapled his ball sack. We’re recording people’s lives. Shakespeare was right, all the world is now a sound stage.”

Harris’ end game is to be very commercial now. But he also wants to take over the Pompidou Center in Paris and build this future in the present. He describes it like a chicken factory, filled with birds who’ve had their beaks cut off. Harris thinks it will work very well at the Pompidou because “Parisians appreciate perspective.”

“I realize power and influence are motivators, but what is it about Internet popularity that gives humans happiness?” I ask.

“If the chicken without a beak is born in the factory does he know what unhappiness is? You’re thinking like you now, but in the post-hive world you’ll have lost your sense of individuality when you’re just porting around the brain. I feel like your tech shrink. You’re judging. Try not to judge. Just reflect what’s there. You try to keep all the baggage you carry with things out of the equation,” he answers, chewing on his soggy cigar.

“So what is the point? How will The Wired City or your chicken factory in Paris benefit humanity?” I ask.

“The upside will be once I’ve completed the accelerated experiment and brought it to the table, we’ll have at least a 3-10 year buffer to figure out how to handle society when everyone’s brains go into multi-task mode,” says Harris.

If Harris’ harrowing vision of the future is one of many possible futures, it’s undeniable that experiments like The Wired City or his chicken factory in Paris will only accelerate that time until we reach that future, thus making it all the more likely to happen. If you buy this, then his financiers will become his enablers.

But Harris doesn’t necessarily want this future. He says he doesn’t judge, he just observes. The man who says he’s never been in love believes building The Wired City is his destiny, as if he was programmed from birth to do so. He’s either a brilliant man who doesn’t understand humanity, or perhaps he understands it all too well. Is Harris the Warhol of the Web, giving people their 15 minutes of fame every day? And is he right to assume that given our natural human tendencies, everything will unravel so perniciously?

“Do you think I’m an eccentric?” Harris asked me around 10pm at the end of the interview.

“Well,” I told him, “You’re definitely not boring.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.