During last night’s democratic debate we were once again inundated with calls from politicians who sought compromise from Silicon Valley in its on-going battle with terrorism. Encryption was the point of contention.

The candidates echoed previous statements regarding the dangerous world we live in. The reason for danger, or so it goes, is the inability of law enforcement to pursue threats from terrorists, both domestic and international, who are increasingly reliant on encryption to communicate.

The sentiment is true, albeit misguided, but more on that in a moment.

Currently, the argument is painted as black and white, a “you’re either for us, or against us” exchange that leaves average Americans scratching their collective heads wondering why Silicon Valley isn’t stepping up the fight against terrorism by cooperating with government.

Arguments, even this one, are rarely binary.

In fact, from a security standpoint, the compromise the government seeks is impossible.

“Technically, there is no such backdoor that only the government can access,” says cyber security expert Swati Khandelwal of The Hacker News. “If surveillance tools can exploit ‘vulnerability by design,’ then an attacker who gained access to it would enjoy the same privilege.”

Microsoft MVP of developer security, Troy Hunt adds:

Good encryption is predicated on the assumption that the implementation is secure unless everything other than the private key is known. This is the core of Kerckhoffs’s principle:

A cryptosystem should be secure even if everything about the system, except the key, is public knowledge.

Either the key is shared beyond those having the discussion and communications are fundamentally compromised or the crypto is weakend as such that it breaks Kerckhoff’s principle. There’s a very good reason the world’s best cryptographers are saying that what is being asked is simply infeasible.

The encryption smear campaign

For all that encryption does for us, it has become a quagmire of political talking points and general misuderstanding by citizens and I’d argue, politicians.

“The truth is that encryption is a tool that is used for good, by all of us who use the internet everyday,” says famed computer security expert Graham Cluley.

“Encryption is a tool for freedom. Freedom to express yourself. Freedom to be private. Freedom to keep your personal data out of the hands of hackers.”

The term itself has become a bit of a paradox. Numbers paint a picture of citizens who think it’s important but have no real idea of how and where it protects them.

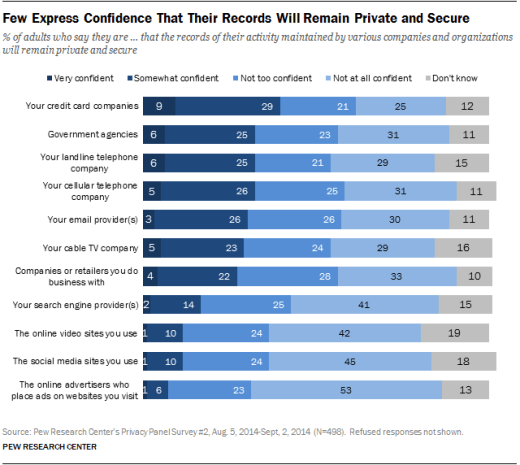

According to a Pew Research report, fewer than 40 percent of US citizens feel their data is safe online, yet only 10 percent of adults say they’ve used encrypted phone calls, text messages or email and 9 percent have tried to cover online footprints with a proxy, VPN or TOR.

These numbers demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of encryption and further detail its public perception.

It is, after all, only natural to attempt to protect yourself when you can foresee a threat, yet US citizens have a rather apathetic view of the very technology that could make them safer.

According to the experts I spoke with, they all seem to agree that there are two reasons people aren’t taking more steps to remain secure.

- Barrier to entry: These technologies feature a lot of jargon and many aren’t all that user friendly. PGP for example, the email encryption technology used by Edward Snowden to communicate with Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald, involves relatively-foreign setup instructions for your average citizen.

- Negative connotation: Most Americans don’t realize they use encryption every day of their lives. Instead, they know encryption as the tool terrorists use to send private messages, recruit new members and spread propaganda online. This is largely due to the on-going encryption debate.

This debate, whether planned or incidental, is doubling as a smear campaign for the very suite of tools that keeps us secure.

It wasn’t mentioned amongst our expert panel, but journalist Glenn Greenwald noted a third reason more people aren’t protecting themselves; they don’t feel they need to.

Over the last 16 months, as I’ve debated this issue around the world, every single time somebody has said to me, ‘I don’t really worry about invasions of privacy because I don’t have anything to hide,’ I always say the same thing to them.

I get out a pen. I write down my email address. I say, ‘Here’s my email address. What I want you to do when you get home is email me the passwords to all of your email accounts, not just the nice, respectable work one in your name, but all of them, because I want to be able to just troll through what it is you’re doing online, read what I want to read and publish whatever I find interesting. After all, if you’re not a bad person, if you’re doing nothing wrong, you should have nothing to hide.’

Not a single person has taken me up on that offer.

Silicon Valley isn’t backing down

So far, the term “debate” may be more of a misnomer. Silicon Valley isn’t debating anything. There may not be anything to debate in the first place.

You can’t “compromise” on weakened security; either it’s secure, or it isn’t.

This veritable Pandora’s Box the US Government wants to explore would lead to backdoor access into our personal lives not just for the government but for hackers and bad actors around the globe. And once you open it, there’s no going back.

“You can’t have secure encryption with a government backdoor. Those two things are mutually exclusive,” notes cyber security thought leader at Script Rock, Jon Hendren. “‘Working with Silicon Valley’ is essentially code for ‘Giving us a backdoor into the accounts, data, and personal lives of users’ and should be totally unacceptable to anyone who even remotely values their privacy.”

There’s also the issue of trust. Even if these backdoors weren’t creating vulnerabilities for bad actors to attack, do we trust the government with our data in the first place?

Our expert panel says, no.

“Handing over such backdoor access to the government would also require an extraordinary degree of trust,” says Khandelwal, “but data breaches like OPM [Office of Personnel Management] proved that government agencies cannot be trusted to keep these backdoor keys safe from hackers.”

Hendren adds:

[…] even if it were computationally infeasible to crack, there’s still the problem of trusting regular people with the fact that this ability would exist.

As we’ve seen with things like the NSA, ‘governmental spying’ isn’t a small-time operation like Barack Obama and a couple generals crowding over a single laptop, it’s entire teams of contractors and employees spread out around the world. If the government had a way in, you may as well not have encryption at all.

Compromise, in this case, is a rather contentious point of view. The compromise the government seeks isn’t a compromise at all; it’s a major loss of privacy and security for everyone.

Clulely shows us how this “compromise” might play out.

1) Companies allow governments to access encrypted data through some technical means which involves compromising and weakening user security.

2) Governments insist that companies do not offer their customers strong encryption in the first place.

The third option is to keep things as they are, or further expound on the efforts to secure the internet.

There really is no middle ground.

Would providing a backdoor help to fight terrorism?

Since fighting terrorism is the narrative in which the government is using to attempt to stamp out encryption, you have to wonder if encryption is truly the thorn in its side that government officials claim it to be.

It’s well-known that ISIS is using encrypted chat apps, like Telegram, to plan attacks and communicate without detection, but would a backdoor have any effect on the surveillance or capture of extremists?

“A backdoor would also have a limited window of efficacy– bad guys would avoid it once that cat is out of the bag,” says Hendren. “This would have the effect of pushing bad actors further down into more subtle and unconventional ways of communication that counter-terrorists might not be aware of, or watching out for, lessening our visibility overall.”

Khandelwal agrees:

Why would any terrorist or criminal use a backdoored service when it is so easy for anyone to create his or her own end-to-end encrypted service, like ISIS has with its own encrypted chat app “Alrawi”?

It’s naive to believe that an extremist group that recruits and grooms new members from the keyboard, not the battlefield, isn’t tech savvy enough to find a new means of communication as current ones become compromised.

The privacy debate isn’t going anywhere. Moreover, the ambient noise created by politicians spouting off about technologies they don’t understand should grow in volume as we near the primaries and then the general election.

What’s clear though, is that this isn’t a debate and that Silicon Valley has no means to compromise.

Without compromise, the government is left with but one recourse, policy. One can only hope that we have leaders and citizens who better understand the need for encryption before that day comes.

In this debate, no one is compromising — or compromised — but the end user.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.