We’re getting closer to the vehicle automation dream. No, I don’t mean Elon Musk’s self-driving Level 2 nonsense. I’m talking about vehicles that can function without any human intervention. But while the tech itself is evolving and going through growing pains, there’s a problem: inadequate road infrastructure.

While there’s been huge investment in developing vehicular autonomous driving technology, there’s been little by cities in the infrastructure necessary for vehicles to communicate with each other (vehicle-to-vehicle), or their surroundings (vehicle-to-vehicle infrastructure).

For example, digital signage and traffic signals that can communicate with vehicles — or pedestrian detection systems — can “teach” a road to warn a driver when a pedestrian is at risk and feed data into a vehicle.

So, the question is: do we need dedicated lanes or corridors for autonomous vehicles? And how can we get from our current state of affairs to mass adoption?

Michigan’s autonomous vehicle travel corridor

One of the most interesting projects regarding custom roads for self-driving vehicles is taking place in Michigan. Here, they’re developing a 64 km (40 miles) travel corridor between Detroit and Ann Arbor for connected and autonomous vehicles.

Michigan was an early adopter in autonomous vehicle legislation.

Last year, the state’s senate introduced a bill (SB 706) to designate specific segments of state roads as “automated vehicle roadways.”

The corridor project kicked off in 2019 and is led by Cavnue. a company from Sidewalk infrastructure partners. Alphabet is an investor in Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners, alongside the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan and StepStone.

The original project pitch from Cavnue writes about infrastructure as “the difference between a siloed future and an integrated future for mobility.”

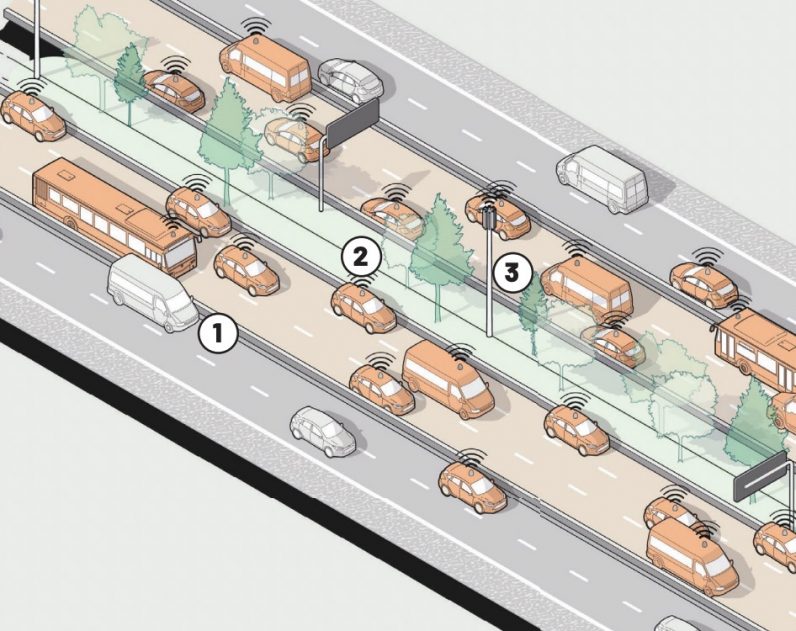

These lanes will include technology to help vehicles connect to roadway infrastructure, creating a digital twin of the road environment. It will likely utilize connected buses and introduce public transit first, followed by shared mobility, freight, and private vehicles.

This will be similar to managed roads with access restrictions, such as express lanes or high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) routes.

For all of this to work, the dedicated lanes must meet minimum, open standards for connectivity and autonomy.

Playing nice

The biggest challenge is the development of these standards — and the project is a great way to iron out the problems before they’re applied nationally.

But this is far from a done deal.

Non-unified communication standards and data management failures may hamper useful applications, such as coordinating braking or optimizing traffic at intersections.

Yet, done well, standards could facilitate the tech to alert vehicles to nearby accidents. It can minimize congestion or prioritize emergency vehicles.

This is all the stuff we’ve been promised with autonomous infrastructure, but few have thought about how they work seamlessly with each other.

The project pledges to follow best practices, including those laid out by standards organizations (like SAE International) and federal agencies, such as the National Highway Transport Authority (NHTSA).

But getting everyone to play nice — especially when you add shared mobility into the mix — is no mean feat.

A dedicated corridor for autonomous trucks

While the Michigan project is likely to start with an autonomous bus, I find the idea of an autonomous truck corridor particularly compelling. It could even come with charging infrastructure embedded in the road or an overhead electric power line to provide constant power.

It means that freight trucks can travel at higher speeds, closer together, and without stopping.

This isn’t just a pipe dream.

In December, Embark trucks announced the launch of a new autonomous trucking lane between Houston and San Antonio.

Houston is at the center of key 965 km (600-mile) trucking lanes, which are ideal for automation, as they cannot be completed in a single day by a human driver due to hours-of-service limitations.

Hauls on such lanes can see rapid improvements in speed using autonomous freight.

For example, a 600-mile run could take approximately 22 hours to complete manually if complying with federal hours of service rules. That same run would take just 12 hours to complete autonomously.

Will autonomous corridors mean bigger roads?

The elephant in the room is that building autonomous vehicle corridors in the short term will require relinquishing an existing lane, or building a new one.

And when road users such as ebike and escooter riders are fighting for dedicated space — not to mention adequate sidewalks for pedestrians — this could mean that highways get a lot bigger in the short term.

Then there’s the challenge of whatever infrastructure is needed to augment the connected corridor. Add parking spaces for people at the autonomous bus station, EV charging points, bike racks, and (hopefully) adequate pedestrian infrastructure, and the enterprise gets exponentially bigger and more expensive.

Dedicated lanes for autonomous vehicles are a fantastic idea, but we’re already facing huge issues around how we design and move people around cities. Creating more roads while governments are trying to reduce their use is not an easy sell.

Despite this, the creation of autonomous corridors could lead to a less crowded and more efficient use of highway infrastructure. There are just a lot of actions and decisions required before we can get anywhere near mass adoption. But it’s nice to dream.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.