By now through mainstream and alternative news organisations, most of us are accustomed to seeing user-generated content (UGC) images or photographs that have been taken by non-professional photographers, often created with a mobile phone.

Along with the emergence of this source of video and stills photography is the rise of the mediator. They want your images and they want to broker a deal for them when it comes to use for ad agencies, news organisations and publishing.

Are you ready to use them?

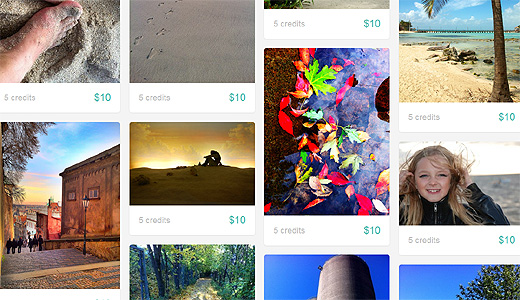

Two of the newer kids on this block are Scoopshot and Foap. Both provide ways in which money can be made for images that are placed with them.

Foap, based in Sweden, offers a 50/50 split for your pictures if they get sold. It has mostly been working in Scandinavian countries and is now available globally. The system works through an app, currently available for free from the App Store and an Android app is in the works.

Each image sells for $10 and you earn each time a company buys your pic. The service is integrated with PayPal as a way to get your money.

You tag your photos so that they can be searched more easily and send them in for approval which takes about 24 hours. Then the images go live for sale.

The peg? Foap screens images for quality. Sharpness or colour are welcomed and the company says that it has a team of experts working on approval for sale.

Foap also has a community element where other users can rate your images. You can follow each other and see which images are popular. It’s not a bad way to train people to select images that are more likely to sell.

Scoopshot is quite a different proposition. The company is based in Finland and works with user-generated content as well as professional freelancers.

It brokers deals in three different ways. Users can upload images for sale via an app – Android or iOS. Media companies such as news corporations, ad agencies and other publishers can sign up to view the images and select those they might want to buy.

Scoopshot also has a Pro service in the works. This part of the system will launch fully later this summer and revolves around tasks. Basically it is a pool of professional freelancers and media companies can task or commission work.

The pool of photographers is world-wide and so this can mean a lot of choices for getting a particular image organised. If there is more than one photographer available for the task, then pricing and portfolio come into play and the media company gets to choose which they might prefer based on past works or how much things might cost.

Interestingly some publications have started to mark images that have been sourced via Scoopshot and pointed to the price paid for the images. You can see an example in the picture below.

There are many other options for pro and pocket rocket photographers of course, but how and when is a good time to consider using them?

Choose your weapon

Paul Clarke is a professional photographer based in the UK. He prefers to use his own brand and means to get work and does very well from his own reputation and works consistently to earn his living.

“I think there are circumstances where by surprise you want a professional intermediary. The case that comes to mind for me is that of @RadioKate who took a photo of a fox on an escalator on the London Underground and she had a massively viral image on her hands and she used a professional picture agency there and it was a wise thing to do as she made a lot of money.”

“So there are cases where an intermediary can be very helpful. But you do have to question if there is substantial value coming back to the person who captured the image. I have no reason for these services I don’t see a value in it for me.”

Should people be paid for their images? Scoopshot have based its business values on this and Clarke says that this can be identified easily with a simple question when approached by a media company.

“I always ask them if they see value in it. If they are making money from the derived value of that image then I should get a part of it. Naturally they do value it if they want to use it.”

Making the news

In the field of news photography, user-generated content has become increasingly important. Eyewitnesses are often in places that would take reporters a day to get to and so it would be foolish not to encompass this area of news gathering into any modern operation.

Many news organisations have mechanisms for image and video contribution built into the applications they also broadcast through for mobile. Most news websites now also have a call for tips and other material. But how are rights negotiated and with a topic like news, can verification be assured?

Turi Munthe is the CEO and founder of Demotix, the online news agency with a pool of approved and reliable reporters that are both pro and semi professional. It has an outstanding reputation for the veracity of its works and relies upon that to strike deals with news outlets like the Guardian, the Wall Street Journal, Telegraph and Times newspapers.

“We’ve built a reputation on both sides so that we can sell on the part of our contributors and so that companies know they can rely on us,” says Munthe. “We’re not looking for the one break out image, though we do get one occasionally. What we are looking to do is provide broad daily coverage.”

The veracity of images not only concerns the location and time an image was taken. This metadata is often built into image files and is part of the verification process that Scoopshot uses to maintain its standards. Whether images are owned by the people who submit them is also a question that can be trickier to answer, but that is why these organisations tend to have a team to work on these problems.

So what of the large picture houses like Getty that have bought up past independent image brokers like Scoopt. Clarke feels that companies like Getty will reposition themselves, having been known for high quality photographs, that they may also shift to encompass user-generated content too.

Not if, but when

When you have a fox on an escalator yourself, this is when you might want to consider a broker. But making sure you know the difference is bound to need some practice. But it seems that the market is slowly moving toward a more savvy group of mobile photographers who are realising there is money to be made.

“If we are going to commercialize the phone in our pocket and change how we use it, we will change user habits because of the market driver of the image,” says Clarke. “If no one was willing to take that image from you then it would hold no value and that has changed and you might get fifty quid for it.”

Munthe concludes, “If you asked me two years ago, I’d have said most people would be thrilled to have their picture up on the BBC and that would outweigh compensation. The conversation about what things are worth on the web has seeped into everything from music, stories, news and images. That conversation about who owns what and what intellectual property means is part of common discourse now.”

Image Credit: Phillie Casablanca

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.