One of the pieces of advice I hear regularly for startup founders looking for a business idea is to find a problem they’re experiencing and set out to solve it. It’s excellent advice – some of the best companies have been built on that premise – but it also has an enormous blindspot.

If tech entrepreneurs come from similar economic backgrounds and demographics, then the solutions they come up with will cater primarily to the needs of their peers.

Take an app like Uber. When it first launched, it made on-demand car service more affordable. Its pricing, however, still meant that only upper-middle class folks could take advantage of it. To Uber’s credit, the company has since rolled out other offerings priced for a wider percentage of the population, and it has worked to ensure drivers make a living on the platform. But, Uber still has little impact on the large percentage of Americans that must rely on public transportation to get to work.

Even as the tech scene in Silicon Valley faces criticism for being insular and privileged, multiple factors have combined to make now a great time for technology to improve the lives of the traditionally “non-tech” crowd. For one, connected devices have reached a significant footprint in the US. In the early days of computing, startups were building for a limited audience. The first PCs were mostly used by scientists and engineers, but computing is now readily available.

The rise of mobile devices has piggybacked off the progress made with PCs to bring technology to a wider section of our society than ever before. Today, many low-income families use smartphones as their primary devices, often skipping a PC altogether.

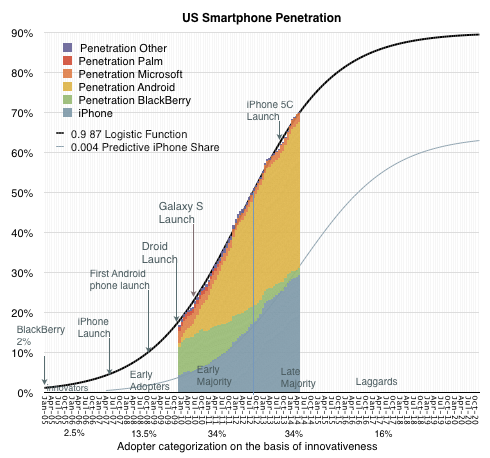

Asymco analyst Horace Dediu recently described the US smartphone market as in the “Late Majority phase” with roughly 70 percent market penetration. That figure is expected to approach 90 percent by 2020. As the smartphone reaches near-ubiquity, products that resonate with the lower segment of incomes will represent a sizable opportunity for new companies.

Touchscreens and mobile interfaces have also advanced enough to make it easier for people to start taking advantage of technology. Just about anyone, from children to the elderly, can get started on a smartphone or tablet. That’s an improvement from before, where folks who were starting out with a computer would need to take classes to learn.

Tech education is also much more readily available. Online courses offer affordable ways to learn to code, and access to devices isn’t limited to just top-tier universities with big computer science budgets. These shifts in education can make it possible for low-income Americans to build their own tech solutions to problems. They’ll also be best positioned to give back to their own community when they succeed.

We’re encouraged by the growing number of companies that are seeing beyond their own circle of friends to create technology that can help the underprivileged. Thankfully, there are more founders working toward a positive social impact than we have the space to highlight. For this article, we spoke to the teams behind Blue Ridge Foundation’s Significance Labs, mobile wallet app Wipit and international gift card service Quippi learn more about the joys and challenges of designing for America’s working class.

Next up: Significance Labs | View as one page

Image credits: Mark Wilson / Getty Images, Asymco

Significance Labs

For those trying to help the fortunes of the underprivileged from a position of relative privilege, one of the first problems they’ll run up against is understanding what the true needs of the community are. Without the necessary first-hand experience, there’s a risk of simply projecting problems and solutions onto the demographic.

Blue Ridge has been incubating tech ventures for 15 years, but it just launched Significance Labs’ Solve for {S}ignificance fellowship earlier this year. The program involved a 3-month fellowship for five entrepreneurs and teams that focuses on helping them to build empathy for their customer base before building their products.

Significance Labs aims to help American families that make less than $25,000 per year. By its count, there are roughly 25 million people who fall into that category.

“What we centered on…was this notion that a lot of the benefits of technology are primarily accruing to folks that were already well off. They’re not targeted at folks at the lower bracket,” Significance Labs co-founder Hannah Wright said. “Our hypothesis was that it’s really hard to design technology for people that you don’t know. With things that you’ve never experienced yourself, it’s harder to design well-fitting solutions for them.”

Significance Labs CTO Bill Cromie, who served as technical founder for two startups in New York before joining the program, put it this way:

If you have the ability to build something, anything – a cabinet, a chair, a boat or software – you build those things to solve your own problems, to scratch your own itch. Everyone is their own best and first customer. That’s not a moral fault by any stretch. It’s nobody’s fault that they build a chair and it’s really comfortable for them.

The fellowship’s mandate, then, is to counter startups’ natural tendencies to solve their own problems, by getting founders to first listen to underprivileged people talk about their obstacles.

After launching the program in March, the foundation received more than 150 applications. From those, Significance Labs chose six fellows to participate on five different teams. The group includes the former product lead for Facebook Groups, a journalist who previously worked as a product manager, a pair of founders from a digital strategy consultancy, a former product manager for Facebook’s Growth team and the founder of a startup focusing on college completion. Blue Ridge intentionally chose entrepreneurs that were mid-career, usually with 4-15 years of experience.

The first stage of the program involved sending the fellows out to conduct user research. The team went out and did in-home interviews with working moms, immigrants, and community college students.

“Significance Labs was born out of the idea that if we wanted to help technologists and designers and product managers build products for lower income and underserved communities in the US, [we needed to] find a way to build connections between those two populations,” Wright added.

After spending the first month learning about their target populations, the fellows then moved into building and testing cycles. At this point, the founders began working with teams of designers and engineers who had signed on to help with the project at reduced rates.

In the run-up to a demo day on August 12, the Significance Labs teams thought through next steps for their companies. Entrepreneurs had to decide whether to pursue a for-profit or a non-profit model and figure out how much funding they’ll need to move forward with their products.

Interestingly, Significance Labs operates with a “single mother clause,” which dictates that no one in or associated with the organization can get paid more per hour than the single mothers who come in to help with user research. That’s a bold policy, considering that the compensation rate is $25 an hour and the foundation is based in New York.

Building social enterprises is a tricky business for a foundation. Wright and the rest of the core team have to continually talk through “the tension between reach and importance, or reach and impact.”

“Part of what’s tough is that I think the social sector has historically said, ‘We want to maximize impact, figure out what’s the optimal behavior that people could be doing.’ They figure something out that’s got great impact but really hard to get it to scale,” she said.

Tech startups, on the other hand, are engineered for scale. However, many of them, such as the latest app fads, have massive reach with minimal impact.

“I’ve seen incredibly, incredibly smart people building things that will probably make them lots of money and lots of people will use, but don’t necessarily improve the lives or station of managing the human species in a way that I think is possible,” Cromie said. “Instead of trying to make better selfies, we could try to make a better world.”

Significance Labs includes both reach and impact as part of the discussion early on its process with entrepreneurs in order to aim for the ideal product.

Since products birthed out of the program don’t have to stay in the non-profit sector, there’s also the concern that a Significance Labs startup could go on to have an enormous exit without giving back to the low-income demographic it’s supposed to be serving. The foundation’s approach was to lean on a strict screening process for fellows to ensure they have the right motivation coming in. In short, Significance Labs is trusting its fellows to do the right thing once they graduate.

Significance Labs also counted on the fact that founders in it just for the money probably wouldn’t be drawn to the program.

“It’s a relatively large investment of time and opportunity cost for people who are mid-career and as successful as our five [teams] are,” Wright said. “We feel like they’re really committed so that’s been our internal screen.”

Fellows can take a small living cost from the fund if needed, but the program is otherwise unpaid.

The foundation operates under the assumption that, contrary to some expectations, under-privileged Americans are very strategic and savvy and can discern which products are helping them.

“We believe that, with the folks we’re working with and talking to, to the extent that there’s a product that’s wildly successful, it will be successful because it provides value in their lives,” Wright said.

Wright did say, however, that she’s worried that the startup community can sometimes approach technology as providing a “silver bullet” for low-income problems.

“I think that optimism is great, but the idea that we’re going to be able to build a phone app that triples graduation rates or puts kids in high quality day care – these are complicated problems in complex ecosystems with rules and regulations,” she said.

Significance Labs stresses that it’s important to keep our expectations realistic about what technology can do. For the team, tech is a tool that’s great for solving “small opportunistic problems.” Wright compared its role in alleviating poverty as helping to stave off the proverbial “death by a thousand cuts.”

“There are lots of small challenges. Tech could be a really good way to go after one, and another, and another. If we make lots of small improvements, the cumulative effect on people’s lives could be really positive,” she said.

Part of the importance in starting the fellows off with empathy and user research is to also identify which technologies are available to their demographics. It’s not enough to know that many low-income Americans have smartphones. User behavior has to be studied in order to decide cases like whether to deliver a service over an app or the Web and whether users will have access to data.

“It’s really helpful to understand the technical constraints with which you need to build those products compared to the types of technology solutions you build in comparatively higher-end [circumstances],” Wright said.

The fellowship program isn’t the only avenue that Blue Ridge and Significance Labs have taken to help foster better understanding between the tech community and underprivileged Americans. The foundation also runs other programs, such as a half-day of shadowing that brings tech workers to talk to and hang out with students and citizens.

The goal is to provide options for different levels of availability. Not everyone can take three to six months off to build a company from scratch, but some can help out for a weekend or an afternoon.

Still, when it comes to the fellowship program, Significance Labs is hoping to cycle of the fellowship process in order to show the importance of having authentic user conversations as you build a product.

“What I think the power of what we’re doing is giving opportunity for people who have a powerful skill set – a skill set of building tech and building solutions – and giving them an insight, a means and a method for helping a population that’s been traditionally underserved by the tech community. I think the desire is very much there, I think the path and the platform aren’t. That’s what we’re trying to provide: path, platform and the opportunity,” Cromie concluded.

The Fellows

To hear first-hand experience about how the program went, we spoke to two of the fellows, Jimmy Chen and Ciara Byrne, several weeks into the program.

Chen came to New York from Silicon Valley after spending two years at Facebook as a product manager and two years at LinkedIn as a junior product manager.

“One of the reasons I got interested in Significance Labs is the argument that a lot of the social good created by tech companies is unevenly distributed…a lot of low-income folks are being left out,” he said. “You could imagine a single mom with two kids trying to finish up at community college. She can find photo sharing apps and fun games, but there’s not a lot there that address her day-to-day needs directly.”

During the research phase, Chen conducted numerous in-person interviews and visited potential users in their homes to have frank conversations about their lives. In his view, taking the time to listen to the community provided context around who would be using his product.

A pattern that he noticed while meeting with folks was a general dissatisfaction with the process of enrolling for government benefits.

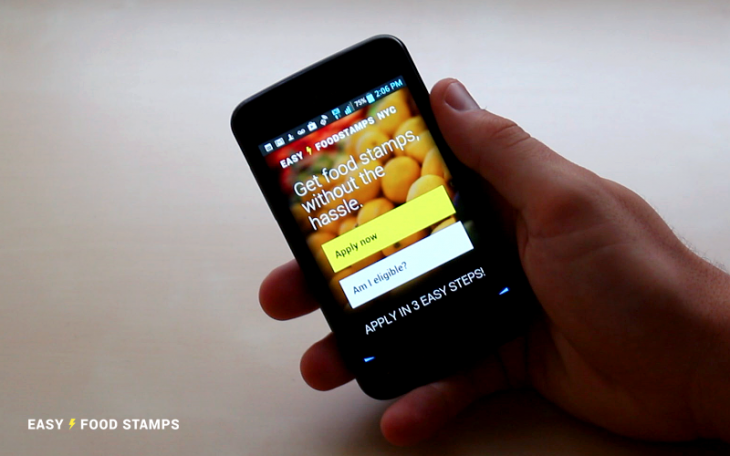

To that end, Chen is building Propel, a “mobile Turbo Tax” for applying for food stamps. In the same way that tax filing software sits on top of the tax code and ensure we’re getting the maximum refund, Chen’s product would serve as an unofficial API for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

“We can’t save the world with the program, we need to set our sights on something that’s feasible,” Chen said. “The way that I think about it is definitely not trying to parachute in and make an app that will change someone’s life, but we can provide a lot of utility.”

For her part, Ciara Byrne previously worked as a software developer before transitioning to writing about tech. Significance Labs co-founder Parker Mitchell originally pitched the program to Byrne for her to cover as a journalist, but she turned around and applied last minute for the fellowship instead.

“My thought process was: per the course of my tech career in startups and companies, I got to work on really interesting stuff, challenging stuff, sometimes fun stuff, but nothing I thought was really important,” she said.

Another factor in her decision was that her time as a journalist had her jumping from subject to subject and she wanted to take time to go more in depth in a field. Byrne came to Significance Labs without a specific idea in mind, so she went into the interview phase searching for a need to fill.

“One of the biggest problems for me has been narrowing it down and picking a focus area. This isn’t like a traditional accelerator where you have a product coming in. We just had a target population,” she said.

After a representative for the National Domestic Workers Alliance came to talk to the group, Byrne decided to build Neat Streak, a tool for helping housecleaners manage their client appointments. She was drawn to helping domestic workers because roughly 95 percent of them are female, they’re often undocumented immigrants, and wages tend to be low with few regulatory protections.

While on-demand cleaning startups, such as Homejoy, already exist, Byrne wanted to focus on creating a service from the cleaner’s point of view. Here’s her description of the product:

NeatStreak is a mobile tool which lets housecleaners create clear cleaning agreements with clients by selecting tasks from a cleaning menu, adding custom tasks and recording what the entire cleaning job will cost. Clients can use NeatStreak to review the cleaning agreement and give feedback after a cleaning appointment.Spanish-speaking cleaners can use NeatStreak in their native language while clients receive all communications in English or vice versa.

The first class of Solve for {S} fellows has cast a wide net when it comes to the demographics of their expected users. While we only talked to two of the participants from Significance Labs, the other products coming from the rest of the fellows include:

- ReBank, a service from Stephanie Raill Jayanandhan and Avi Karnani for helping underbanked populations find affordable banking services

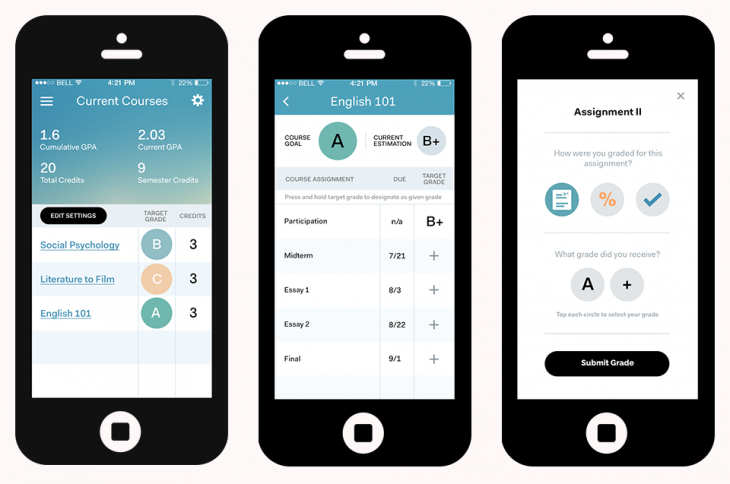

- OnTrack, a mobile dashboard by Margot Wright that helps students keep track of financial aid eligibility, academic performance and upcoming assignments

- EasyDroid, a launcher and screenshare app by Shazad Mohamed that helps elderly Android users get the most out of their phones

Many of these products aren’t a natural fit for the traditional Silicon Valley funding pipeline. In setting out to help unreached demographics, these startups will have a tougher time with user acquisition. The limited scope will also make it trickier to reach massive scale, and founders will have to get creative with their business models. Still, these are products that deserve to be built, and we’re eager to see how things progress. If successful, Significance Labs’ model could inspire new batches of community-driven tech products for underserved populations.

Next up: Reaching the Underbanked and Tech for Immigrants | View as one page

Image credits: Significance Labs, Oleksiy Mark / Shutterstock

Reaching the Underbanked

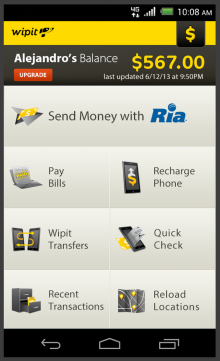

Plenty of companies are tackling the mobile wallet space, but most of them are focused on reaching customers who already have bank accounts. Wipit, however, sees an opportunity to build a mobile financial service that works for the same group of people who buy prepaid cellular service. The company provides the technology behind Boost Mobile’s Mobile Wallet service.

“We’re specifically targeting this underserved community of prepaid wireless customers, the unbanked and underbanked,” CEO Richard Kang said. “To move the needle that will make a positive difference, we need more than just philanthropy. We need a sustainable, profitable business model that does good as well.”

Wipit revolves around the same online-offline experience that prepaid mobile operators use. With Boost Wallet, you have the option to add cash to your account at retail stores. For Kang, the inclusion of the retail experience is core to Wipit, as it adds a familiar human interaction that helps customers make the jump to a mobile wallet. Alternatively, customers can set up direct deposit with payroll or government assistance checks.

Wipit revolves around the same online-offline experience that prepaid mobile operators use. With Boost Wallet, you have the option to add cash to your account at retail stores. For Kang, the inclusion of the retail experience is core to Wipit, as it adds a familiar human interaction that helps customers make the jump to a mobile wallet. Alternatively, customers can set up direct deposit with payroll or government assistance checks.

Reaching the underbanked comes with its own set of challenges. Kang described the current financial regulatory environment as “tumultuous,” noting that laws are changing to adjust to technology. Stricter identity verification requirements, for instance, make Wipit’s job harder.

Also, investor interest tends to be lower for companies targeting an unconventional demographic.

“A lot of the investment hype and energy goes into the cool First World services. People who are making the big decisions get those products because they can imagine using them,” Kang said.

When Wipit first started pitching its product, Kang had people tell him he was crazy. Some didn’t believe prepaid customers would upgrade to a smartphone, while others were incredulous that there were people who would choose not to have a bank account.

“It’s hard for the people who have power to relate, to see that there’s something valuable and interesting there,” Kang said, adding that he’d heard from a well-known VC that most Silicon Valley investment dollars go toward serving “the people who are on the Google bus.”

Wipit is backed by Core Innovation Capital, the investment arm of the Center for Financial Services Innovation, which is a network for companies building financial products for the underbanked.

Considering that most of Wipit’s team probably has bank accounts of their own, I was curious what steps the startup took to make sure that it’s actually meeting the needs of its user base instead of projecting them. Kang said that in addition to using Wipit, the team approaches the problem by getting in tune with the customer from a sales and marketing perspective.

“We have a long history of being able to sell and market services to the unbanked and underbanked. We’re relying on expertise in that particular area,” Kang said.

For instance, Boost Mobile’s network of independent dealers help validate whether Wipit’s products are really in touch with their user base.

“These store owners are really close to the consumer. They see them every day, in many cases they live in the same neighborhood. The rationality is that the dealer, just by saying, ‘Yes, I want to sell the product,’ is saying, ‘Yes, this product makes sense.’”

Wipit’s dealers also provide regular feedback about features and messaging that Wipit needs to fix.

Mobile wallet adoption among mainstream consumers has been slow, but Kang believes that Wipit’s target market can get more value out of the service than middle-class users who already take advantage of online banking.

“This idea of wallets has been long beaten to death because, for the most part, everybody says wallets have no value proposition,” he said. “I think in most cases that’s true. In our case, for our particular consumer, we’re not just another way to use your credit card, we’re the very first electronic payment mechanism in your life, the very first debit card period. We think we’re approaching and solving real needs.”

Still, Wipit is venturing into difficult territory where its demographic often views technology as scary. That’s why it combines the technological aspect with a human point of contact.

“Very fundamental to our DNA is that people are the things that solve these problems, at least at this point in time they’re the ones that are going to help cross the chasm,” Kang said.

Tech for Immigrants

New immigrants also represent an underserved segment of the American population. Quippi is doing its part with a cross-border gift card service designed to replace international money transfers.

The startup sells gift card codes in the US for top Mexican retailers. Customers purchase the cards at a retail store or on the Web and then share the required PIN code with their family members across the border.

Quippi CEO Michael Aleles started the company with the goal of providing a fee-free financial service for immigrants. The solution turned out to be a pretty simple one: have retailers pay the fees.

Recipients get the full face value of the cards that friends and family send over, while retailers get guaranteed business. Quippi estimates that it puts 5-15 percent more money in its customers pockets by removing fees.

In order to help senders have piece of mind about where their hard-earned money is being spent, Quippi limits its partnerships to basic goods and services, like grocery stores, pharmacies, department stores, electronics and medical services.

With roughly 1/3 of the money sent home by immigrants going to rent, Quippi is focusing on the other 2/3 that is spent at retail.

According to Aleles, US residents send $23 billion to Mexico every year, which would make it the second largest industry in Mexico, behind only the oil business.

While Quippi has set its sights first on reaching the US-Mexico audience, there’s no reason the business model couldn’t work for other communities.

“What we do really works between any two markets in the world where there’s a population in one market supporting families in another,” Aleles said.

Quippi takes pride in keeping its technology in the background so it can offer a “low-tech” solution to the consumer. While 90 percent of the startup’s Web traffic comes from mobile, customers can also order over the phone or purchase at a retail store.

The fact that Quippi is going after an under-acknowledged community gives it a competitive advantage. Aleles continued:

There are very few venture-backed startups that go after the underbanked, underserved. We’re fishing where nobody else is fishing. I spent my career in two places: Silicon Valley and Latin America. This is the blend of what I’ve done. I saw first hand how in Latin America, consumers really get abused by many different industries, but particularly financial services.

We’re offering a service which many others could go do but no one else is doing. The way we look at the world, wherever there are high fees, there’s an opportunity to turn the tables upside down.

Conclusion

Politicians like to lean on the phrase “A rising tide lifts all boats” when discussing economic progress, but the aphorism doesn’t always apply in the tech world. On one hand, low-income Americans have certainly benefitted from new mainstream technologies like the Android operating system and the app ecosystem, but on the other, they’ve also been neglected by the growing number of homogenized tech startups that build products to meet the demands of their own privileged and educated founders and employees.

The underprivileged and underbanked among us have unique needs that deserve their own solutions. Organizations and companies like Significance Labs, Wipit and Quippi are just a few of the endeavors that are working to make tech benefits more inclusive. At the same time, we need to remember the importance of empathy and the limitations of technology in order to build realistic problems that address actual needs instead of projected ones.

The root causes of poverty and lack of education are too systemic for any one startup to address on its own, but our society – press, investors, entrepreneurs, engineers and users alike – can do more to encourage companies to build meaningful products that offer help to the millions of Americans who are often forgotten by the latest trends.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.