It is widely agreed that the African e-commerce market presents a huge opportunity for entrepreneurs and investors alike.

Frost & Sullivan estimates the market will be worth $50 billion by 2018, compared to $8 billion in 2013. E-commerce businesses of various persuasions and sizes are springing up across the continent, and investment money is flowing into the sector.

Yet the truth is more nuanced. Though e-commerce is undoubtedly a long-term opportunity, and investors have not been slow to spot this, at the moment the market faces severe limitations.

The primary issue is that the market is just too small. Only 26.5 per cent of Africa’s over one billion people are connected to the internet, with a recent United Nations report saying eight of the 10 countries with the lowest levels of internet availability in the world are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Those that are online are still wary of shopping on the internet. If we take South Africa as an example, e-commerce accounts for only 1.3 per cent of the total consumer goods market, compared to 14 percent in the likes of the United States and United Kingdom. Africans are still generally wary of buying online, and remain more inclined to use cash.

Scale or die

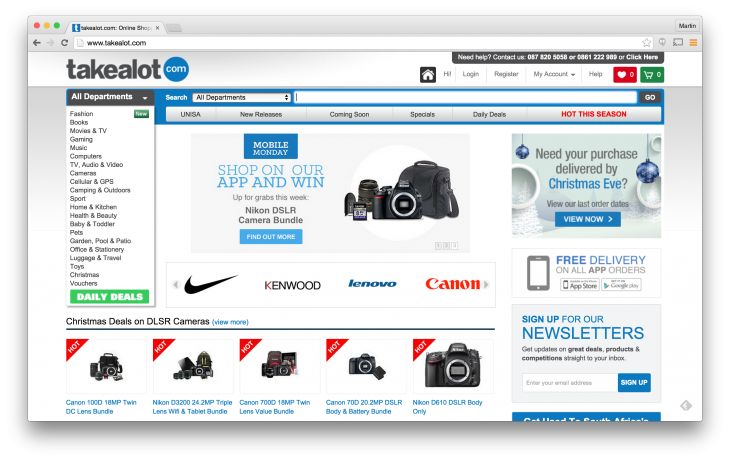

In spite of the well-established long-term opportunities, African e-commerce has been forced to adapt to this current climate. The major example of this again comes from South Africa, where e-commerce platform Takealot had a 2014 that pretty much sums up the state of the market thus far. Despite raising $100 million in funding from Tiger Global, the company was also forced to admit defeat in its efforts to win market share alone and merge with its biggest rival, Kalahari.

“The move was driven by the fact that, without scale, South African e-tailers simply can’t compete successfully against the local brick and mortar retailers and foreign companies such as Amazon and Alibaba,” Takealot said.

Naspers, which owns Kalahari, has itself had a tough year, realizing the need to remove some competition from the market when it closed e-commerce sites SACamera, 5rooms, Kinderelo, Style 36 and 5Ounces in February.

It is not just South Africa where companies are facing these issues. Given the size of its population and growing middle class, Nigeria is generally deemed as one of the most lucrative e-commerce markets in Africa, and has seen a number of major players launch online stores.

But Sim Shagaya, chief executive officer (CEO) of Konga.com, which itself is partly funded by Naspers, said there is still a long way to go to make e-commerce a truly profitable business on the continent.

Building the infrastructure for success

“The biggest challenge to the growth of e-commerce in Africa is the lack of a proper operating systems to coordinate the vast resources the continent has to offer,” he said. “For example lack of robust and scalable logistics infrastructure, particularly small-parcel and final mile to consumer – both of which are essential prerequisites for any retail e-commerce business.”

Shagaya said Konga.com was acting to overcome these issues itself, not least by building its own delivery fleet to overcome the logistics problems that hindered its growth. The main way to help grow the sector, he said, was to focus on delivering exceptional customer service.

Shagaya said Konga.com was acting to overcome these issues itself, not least by building its own delivery fleet to overcome the logistics problems that hindered its growth. The main way to help grow the sector, he said, was to focus on delivering exceptional customer service.

“This is what would make customers come back the next time they need to purchase an item, we must show how e-commerce is value added for them,” he said. “For us at Konga, growth came on the back of us listening to the customer.”

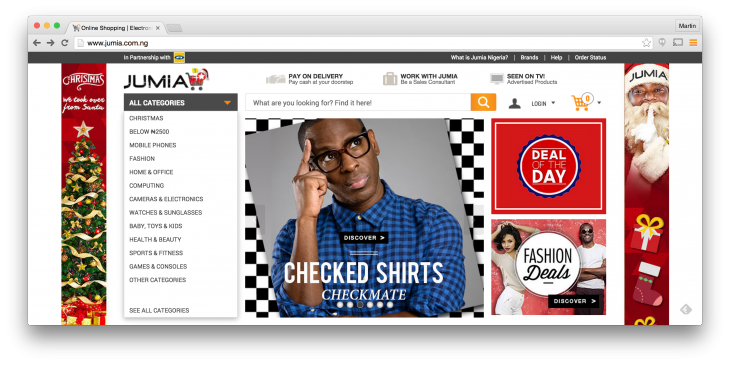

Jeremy Hodara, co-CEO Africa Internet Group (AIG), which owns Konga.com’s main rival Jumia, said his company was convinced of the long-term potential of e-commerce, having created a number of online shops, hotel booking platforms and food delivery services in Africa. But he agreed with Shagaya that there were obstacles that needed to be overcome for this potential to be realised.

“Creating an internet business is easy on paper, one can simply buy a domain and set up a website,” he said. “People are skeptical and predict failure for e-commerce businesses in Africa for several reasons, such as the undeveloped e-payment methods, the lacking delivery system infrastructure and the relatively low internet penetration across Africa.”

The long game

He said for the meantime Jumia had a deliberate policy to focus on customer acquisition and expansion to new territories rather than short-term profitability.

“Companies often struggle between focusing on profitability or further investing. It is crucial to decide if it’s time to make the company profitable or time to invest. If you stop investing too early you will miss part of the opportunity,” Hodara said.

By this token, then, e-commerce companies in Africa are advised to focus as much as they can on obtaining new customers and investing in new markets to make themselves more profitable later on. This explains why Jumia has thrown so much money at expanding across Africa, and why Takealot and Kalahari have decided that together they are stronger in terms of the market share they control.

But some investors are put off by the need for deep pockets and long-term thinking. Paul Cook, founding partner of South African investment firm Silvertree Capital, says his company is invested in many e-commerce businesses but wishes it wasn’t.

“It is definitely the way that retail will be moving, but it is not necessarily the most attractive investment area,” Cook said, saying so many companies were throwing around so much money that it was difficult to go head-to-head.

Though Cook advises focusing on niche e-commerce in order to build a successful business without the need for billions of dollars, this advice is being disregarded by the likes of Jumia and Naspers. For the time being, Africa’s e-commerce giants are involved in an expensive land-grab, and must hope the projections of long-term riches are correct.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.