As a former writer at VentureBeat, the state of media industry in the U.S. has always been important to me. Since the internet boom took momentum, even the world’s most established publications have been forced into a downturn, as they struggle to adapt to monetizing in the new digital landscape. For journalists this has meant less job security due to the constant threat of newsroom cuts and redundancies.

It would be easy to assume after such a tough decade, when American and European media such as the New York Times and The Guardian are having to battle to grow, that this must be happening in other countries all over the world. However, I recently discovered that this was not always the case.

In India, the country with the second largest English speaking population outside of the U.S., the media is evolving in a very different manner than seen in the west. A recent Forbes article by Freddie Dawson cites an official study which shows that the value of the newspaper industry in India has in fact increased by two-thirds since 2010, and according to KPMG is predicted to fluctuate comfortably between 12 and 14 percent for the next few years.

The media industry in India is enormous. There are more than 82,000 newspapers in publication in 22 different languages, catering to more than 1.2 billion people, along with a whole new range of digital offerings which have emerged over the last decade.

Here are three other things you may not know about the media market in India:

Media is driven by the expanding middle class – but the middle class is very different

Up until last year India was the world’s fastest growing economy, and it has a rapidly growing middle class. Coupled with a low internet penetration across the country, this is keeping newspapers relevant and profitable.

A recent study estimates that the Indian middle class doubled in size over a twelve year period, from 300 million in 2004 to 600 million in 2016, and that it now accounts for nearly half of India’s 1.2-billion population.

While literacy rates and the national GDP per capita are rising, the group considered middle class in India is still lagging behind the socio-economic status of those living in more developed economies. Middle class professions include carpenters, street vendors, wall painters and drivers, with lower middle class surviving on between $4 and $6 per capita per day, and upper middle class between $6 and $10.

Rising literacy rates in India –currently sitting at around 75 percent– and an increase in government funded literacy programs for under-25s are playing a big part in bolstering the media industry in the country. When young people learn to read one of the first things they do is pick up affordable newspapers in their own regional languages. The annual subscription for a local paper in India costs just 399 rupees, or approximately $5.80.

The reach of these local language vernacular newspapers is quite astonishing. According to the 2014 Indian Readership survey results, a regional Hindi newspaper Dainik Jagran is the most popular with over 16.6 million readers. Times of India — which has been estimated to be the world’s most widely circulated English newspaper — is the only English newspaper to feature in the top ten.

Media is evolving at different speeds in India

Due to the vast socio-economic differences between classes, different consumption trends within groups in society, and the fact that as many as 22 languages are spoken throughout the country, a unique situation has developed in which television, digital and newspapers are all developing side by side at different speeds within different demographics.

In a recent Techcrunch article Indian media mogul Raghav Bahl, founder of Quintillion Media and board member at digital media platform Quintype, outlines three distinct media groups within the country:

1) Traditional vernacular publications, such as the best selling Dainik Jagran, catering to regional districts. The effect of the digital revolution has been minimal on these publications due to the low internet saturation in the areas where they are popular. However, it should be noted that even some of these publications are having to cut costs to stay profitable. Lokmat, a top-selling Marathi newspaper, uses its factory in Maharashtra to print Maharashtra Times, a regional competitor.

2) More than 20 larger media companies which cover news from the whole country such as the Times of India, Indian express and Hindu. These publications are adapting to the media downturn similar to publications in the US and Europe and are looking to pivot towards digital. However unlike in the west, there is less pressure as these publications still have huge readerships and profitable business models.

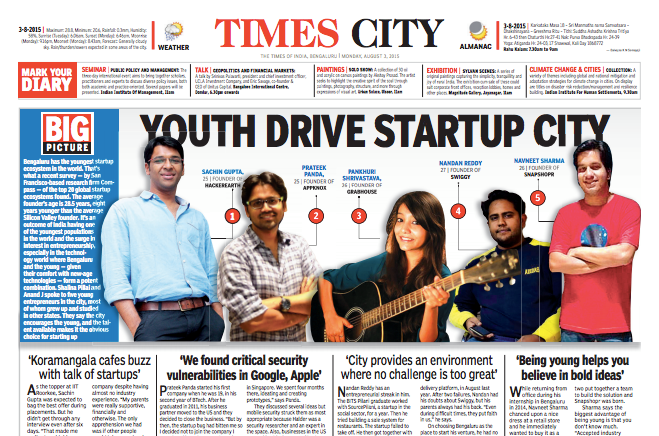

3) There is the new emerging generation of media startups with their eyes set on disruption. These media companies are targeting middle and upper class Millennials. They are technologically agile and cover a wide range of topics such as technology, sports, and business, but have no footprint, and reach small audiences compares to print media.

In a starkly different situation to the US and Europe, where digital publications are coming out swinging, and traditional publications are being pushed against the ropes and being forced to adapt, or simply disappear in India, disruption is gently nudging rather than forcing change. A recent Forbes article shows TV and print media still account for more than two thirds of advertising spending in 2017, but that digital advertising is growing rapidly, and is forecasted to to double to 24 percent by 2020.

In the west, media publications have been forced to experiment rapidly over a range of channels to reach audiences on a range of devices. But in comparison Indian media companies have the luxury of time on their side. Raghav Bahl predicts that digital media is going to grow steadily over the next decade, and enter the mainstream as the expanding middle class adopts smartphones and digital technology.

In India experts have noted a technological ‘leapfrog’ as seen in many Sub Saharan African countries in which many people are accessing the internet for the first time via mobile devices.

India has the world’s second largest smartphone market, with the most popular sales being Android devices costing less than $150. With literacy and GDP levels rising rapidly, and smartphone prices dropping steadily, it looks like within a decade the emerging middle class could soon be picking up smartphones instead of local papers.

Digital and television channels are still considered lower quality by many

In the west, the success of new digital media companies has been pushed by their technological agility, and the fact that innovative millennial directors are creating exactly the right type of content, for the right type of consumer, on the right channels. These companies are new, and not held back by any old mindsets or legacy systems. With plenty of financial backing, they have handcrafted their platforms and content to exactly fit the needs and wishes of modern media consumers.

However, in India despite increased access to affordable smartphones, digital media is yet to become mainstream across other socio-economic groups, due to a general lack in faith in the quality and reliability of news platforms in languages other than English. Broken links, clickbait adverts disguised as news, and poorly designed and maintained platforms, are sending people back to the medium they know and trust, print newspapers.

The same goes for TV news channels. As quoted in The Economist, Arun Jaitley, India’s finance minister recently stated “Newspapers give more clarity to readers who are ‘confused and looking for the facts’ after watching ‘shrill debates’ on TV news channels”.

However, the upper classes in India, who live in high rise luxury apartments, study abroad in expensive western schools and colleges, and are on top of the digital and technological curve, enjoy access to all the same technology and media used in New York or London.

This wealthier socio-economic group has taken to digital media in a big way, and consume their news on apps and local and foreign digital sites across a range of devices and platforms. For early stage digital media companies in India, the challenge is to create content which resonates with different groups in society, and maintains a level of quality and reporting which is on par if not higher than that of mainstream print publications.

In the world of startup news, companies such as Yourstory, Bizztor, The Tech Panda, The Startup Journal and Inc42 are run by forward thinking entrepreneurs who are modeling their platforms and content strategies not on local publications, but rather on the world’s leading publications in the US and Europe. India is now ranked as one of the most active startup countries in the world after the U.S. and the UK, and as such needs high quality news outlets to share its successes within its own community and the rest of the world.

India’s prime minister Narendra Modihas has been outspoken in his support for boosting entrepreneurship and innovation across the country. Mohidas is famous for his slogan “Startup India, Standup India” and launched a government funded initiative for early stage startups called Startup India in 2016, as well as a government supported fund SIDBI Startup Mitra.

This week our media incubator ESPACIO announced the acquisition of The Tech Panda. Since being founded by Prateek Panda in 2012, who is also the Co-Founder of Appknox, The Tech Panda has grown to become one of the country’s most respected sites covering technology, startup news and innovation in English. Other than placing the spotlight on amazing companies and ideas coming out of India, the site provides a space where local entrepreneurs and leaders can share their opinions on a range of topics.

In the same way as the most established and respected tech publications of today, such as TechCrunch and The Next Web, started off as smaller publications run by entrepreneurs, we will surely see players today grow into established names in the future.

The same media downturn which has challenged leading publications across the world will come to India eventually, as literacy rates, GDP levels, and smartphone and internet access continue to grow. However, unlike the tornado which hit the western media ten years ago, the winds of change have been much softer on the other side of the world. Disruption opens the door to opportunity for those who stay one step ahead of change, and with more than 1.2 billion potential media consumers in India, many companies will be competing to be at the head of the pack.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.