There’s two things you should know about Jupiter. First, it would be one helluva planet to live on if you were a werewolf. That’s because it has 79 moons. Second, one of those moons probably has life on it.

We say probably because, based on all the evidence, it would be weird if it didn’t.

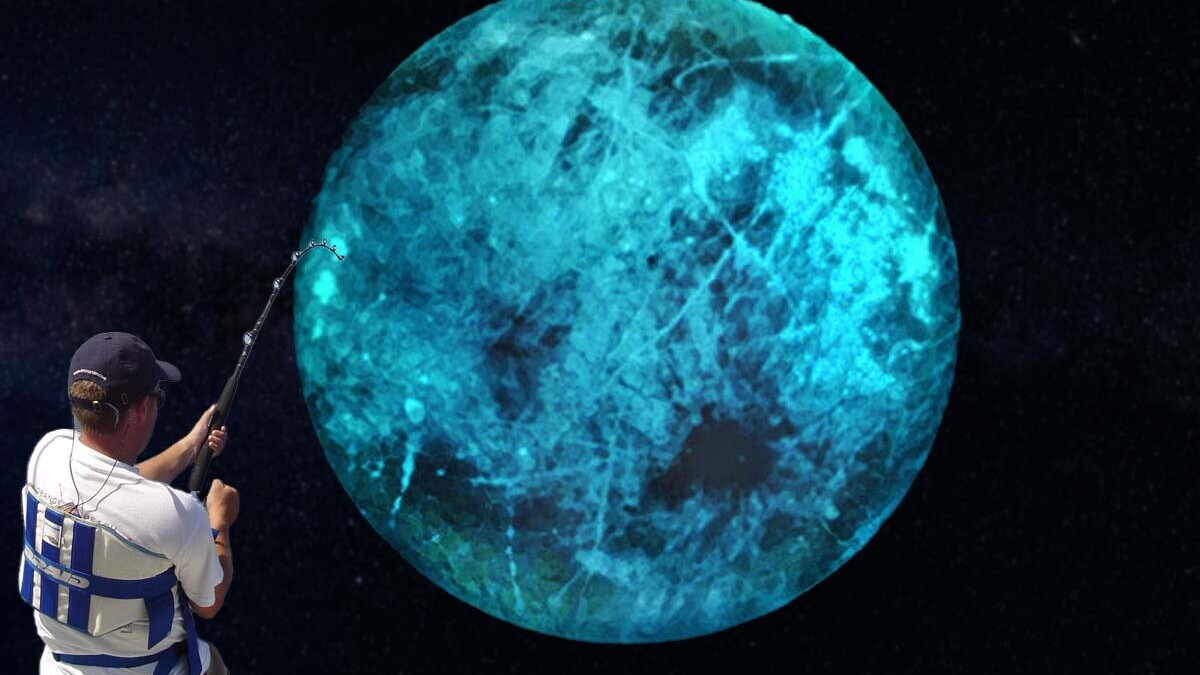

Scientists have long thought Europa, a small icy moon about a quarter the size of Earth, might contain life. After all, it’s supposedly got everything you need to sustain biology as we know it: oxygen, water, and nutrients.

But there’s always been one hitch: Europa’s oxygen and its water are separated by a thick sheet of ice. And, until now, nobody’s been able to hypothesize a way for that oxygen to supply any potential life in the watery parts of the moon’s oceans.

A team of scientists led by Mark Hesse of the University of Austin recently conducted simulations demonstrating a theoretical method by which oxygen could actually penetrate Europa’s ice shell and reach the water beneath.

According to the team’s research paper:

We propose that oxidants are transported through the ice shell by the drainage of near-surface brines formed concurrently with chaotic terrains. We estimate that Europa’s porous regolith contains 3.7 × 1014 to 5.6 × 1018 mol (1.2 × 1013 − 1.8 × 1017 kg) of trapped O2. Simulations of coupled melt-migration and eutectic phase behavior show that brines drain before they refreeze, delivering ∼85% of the surface oxidants to the ocean on timescales of 2 × 104 years.

In essence, the team asserts that salty brine could occasionally form rivulets of draining oxygen from the ice shelf that might allow a significant portion of Europa’s surface oxygen to escape into the under-ocean.

Whew, that seems like a lot of conjecture. But there’s good reason to be excited: if the scientists are right, then Europa is extremely well-suited as a candidate for alien life.

Despite the fact it’s a quarter the size of our planet, its oceans are suspected to be at least twice as big and many times deeper. In fact, many scientists believe they might extend all the way to the planet’s core.

In scientific terms, this is a jackpot. There should be plenty of cast-off molecules captured beneath the planet’s surface to serve as potential nutrients and the myriad chemical reactions that could occur at the seam between the moon’s core and its oceans could make for a perfect simmering pan for the primordial soup of life.

Toss in the fact that these oceans have a protective shell that, according to the new research, could keep harmful radiation out while still allowing oxygen to filter through, and it feels like a near-certainty we should find some signs of life on the planet.

Unfortunately, what we see in simulations is a lot harder to reproduce in the real world. In order to truly determine once-and-for-all whether Europa hosts life, we’ll need to drill at least a foot beneath the surface before we could hope to detect even the most ancient signs.

And, if life still exists on the moon, we’d likely have to go significantly deeper to observe a living specimen.

Currently, NASA has plans to send a vessel to Europa in 2024 to scout out spots for a potential drilling mission in the future.

In the meantime, the organization is busy scrambling to meet its self-inflicted deadlines for crewed missions to Earth’s moon and Mars.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.