This post originally appeared on the ooomf blog.

I have a pretty bad memory, it seems. I know people say that all the time, but here’s why I think it actually applies to me:

- In pretty much all of my childhood memories, I’m around 10 years old, as if nothing ever happened before that.

- My poor co-founder, Josh, has to replay almost entire conversations before I recall having had them. On a regular basis.

- Unless my high school was running way off the curriculum, I just don’t remember anything I learned there. Everytime someone asks me about a high-school level concept in science, or maths or even something I should know as a writer, like what a past participle is, I draw a blank.

It’s a bit of a struggle having a bad memory. It makes conversations frustrating (mostly for the other person), makes a lot of tasks take longer because I have to look up things I should remember, and it means I usually need some basic introduction to any topic before I can follow the latest news.

Since I’ve been reading and writing more about the brain, memory is one area that’s really fascinated me, because I’d like to improve mine. So today I had a look into the basics of memory: how it works, what types of memory there are and why our memories aren’t as reliable as we think.

How memory works

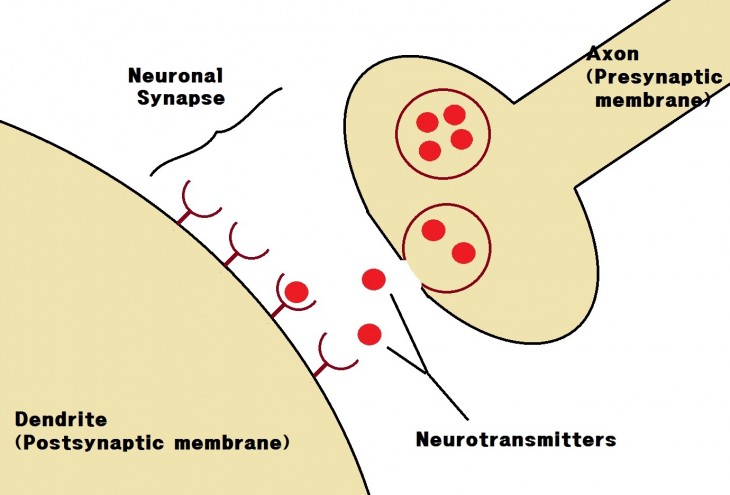

Creating memories, like learning new things, is all about creating and strengthening connections between the neurons in our brains (called synapses):

When we create a new memory, a pattern of brain activity occurs, and we store what’s called a memory trace. This is like the seed of the memory, before it gets strengthened and grows by connecting to other, related memories we have.

To make sure we hang on to that memory for the long-term, studies have shown that our brain recreates that exact same pattern of brain activity while we sleep. This is known as memory consolidation.

Obviously the last step, and the one we’re probably most familiar with, is recalling those memories. The way this happens is a reconstructive process. Rather than reproducing an event exactly as it happened, like a video camera might, our memories actually just offer up fragments.

Without realizing it, we stitch these fragments together into a narrative that helps us understand what happened.

The different types of memory

I always thought memory was memory, pretty much, but it turns out there are a bunch of different types:

- Declarative memory: Facts and knowledge, like the capital city or your birth date.

- Episodic memory: Memories about life events, like your last birthday party or your first day of school.

- Procedural memory: Your own how-to manual, essentially. Memories about how to ride a bike or cook your favorite meal.

- Semantic memory: Meanings and concepts that you’ve learned, especially useful for reading.

- Spatial memory: Your map of the world, inside your head. These cover your environment, landmarks and objects.

Each type of memory relies on a different area—or combination of areas—in the brain. There’s one more type of memory, though: working memory.

Working memory is kind of like the brain’s notepad. It’s the place we dump stuff while we’re using it, before either forgetting it or moving it to long-term memory. It’s main use is for temporarily storing small bits of information until we’ve used them up.

Because it’s like a workspace for the brain, working memory is limited in how much we can keep there. The general rule is that most adults can hold 3–5 pieces of information in working memory at a time.

If you’ve ever repeated a phone number to yourself over and over until you dial it, that’s your working memory at play. Once you dial the number, you don’t need to remember it anymore so you let go of it and it disappears.

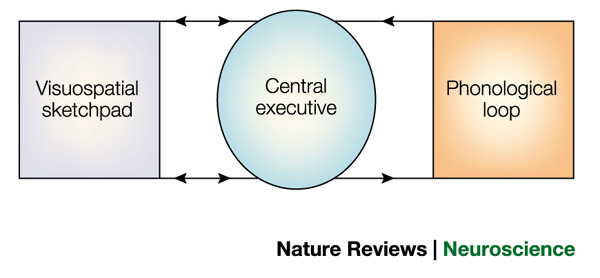

There are a few theories about how this really works in the brain. One of the most popular theories is the multi-component model, which was first proposed in the 1970s. This model breaks down working memory into three parts:

- The central executive, or control centre

- The phonological loop

- The visuo-spatial sketchpad

The central executive is in charge, so it monitors and coordinates the two other parts. The phonological loop processes words and speech-related sounds, like when you repeat the phone number, or if you try to remember a string of words.

The visuo-spatial sketchpad handles information about your environment and objects like size, shape, color and where things are around you. If you’re trying to remember a driving route for the first time, that’s when this part of your working memory would come in handy.

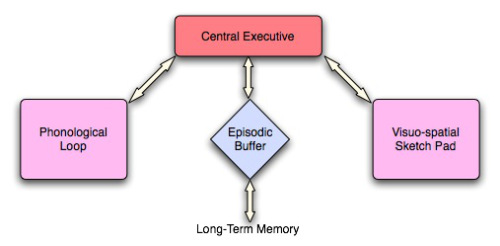

In 2000, the psychologist behind this model, Alan Baddeley, introduced another section that reports to the control centre: the episodic buffer. Theepisodic buffer connects information from the phonological loop and visuo-spatial sketchpad, and long-term memories.

It temporarily holds “episodes” of memories made up of bits of varied information, whereas the other two parts of the model only hold information specific to their related areas.

The last thing to remember about working memory is that it requires your attention. If you’re focused on something in front of you, your working memory won’t take in information about something happening nearby, even if your senses can pick it up.

Working memory is all about the things we want to hang on to, temporarily, and because it’s so limited, it can’t waste space on taking in everything around us.

Why our memories aren’t reliable

Funnily enough, our memories are nowhere near the reliable encyclopedia of life that we think they are. There are a few different ways they can be changed, and most of them happen without us even realizing.

Unstable memories

Remember how I said before that memory is reconstructive? And how we put together memory fragments into a narrative that makes sense to us? Well, this is kind of where our memory lets us down, in a way.

Because we don’t have an exact replica of the event we’re remembering, we’re prone to (subconsciously) add new information that we have now, when we recall the memory, or mix up the fragments we have.

If you’ve heard about people uncovering repressed childhood memories, this is often rebutted with research into how malleable our memories can be. The process of recalling our memories is tainted by our biases and our experiences, and we don’t even realize we’re altering our memories as we recall them.

A good example of this is an experiment done by psychologist Frederic Bartlett. He asked participants to read a story and then retell it. Later, he went back to the study participants and asked them to retell the story from memory at various points, even up to a year later.

What he found was really interesting: not only did the story change, as you might guess, but without realizing it, each person emphasized and removed different details, depending on which ones they thought were important, and they rationalized any parts of the story that had confused them originally. Each person had saved memory fragments about the story, and then stitched them back together into a narrative that made sense to them.

There is an upside to this, however. Some scientists have proposed that the reason we have a reconstructive memory, which requires this fragment stitching process, is because it helps us to predict the future.

Whereas a complete reproduction of a past event might help us to relive that event more clearly, little fragments help us focus on the parts of the past that had an effect on us and to use those to make decisions about events that haven’t taken place yet.

Changing memories

When we recall past memories, something strange happens: the original memory trace that we consolidated into our long-term memory during sleep quickly becomes unstable. This means it’s prone to alteration, and that’s when we tend to subconsciously change our memories during the recall process.

We can actually use this to our advantage in some ways. For instance,emotionally charged memories can be softened over time by recalling them in safe environments and removing the negative associations they bring.

One study on associative memories in drug addicts showed that when they were shown videos of drug use and paraphernalia, it often prompted a desire to use drugs. When participants watched the video ten minutes before an hour-long period of being exposed to those same images, their drug cravings were reduced, because they’d just had a new experience of seeing those images and then not taking drugs.

So over time, the association of seeing drug-related media and drug use could be replaced with new associative memories.

Sleeping on your memories

Sleep is obviously hugely important for a strong memory, since researchers have found that this is when the consolidation process happens. It follows, then, that sleep deprivation can be detrimental to the creation and strengthening of our memories.

Not only does sleep deprivation make it harder for us to consolidate new memories into long-term storage, it also makes it harder to recall the ones that are already there. In fact, after long periods of sleep deprivation, we become more prone to generating false memories—i.e. believing things that never happened are actually real memories.

Improving your memory

Now that I know a bit more about how memory works, I’ll be sure to focus on getting enough sleep. What about other ways to improve memory, though? There are a few things you can try, though research into how well these methods work is still in the early stages so there aren’t any guarantees. But if your memory is as bad as mine, they’re probably worth a try anyway.

- Drink coffee: though studies into the effects of caffeine on memory in the past have mostly shown no effect, one study found that taking a caffeine pill immediately after learning something new would help with the memory consolidation process. So instead of having your coffee first thing in the morning, try starting your day with some reading or a learning exercise (I’m going to try a quick French lesson) before your caffeine hit. This may help whatever you just read or learnt to stick.

- Keep some rosemary around: researchers have found in a couple of different studies that the scent of rosemary can improve cognitive abilities, particularly memory recall. It couldn’t hurt to have some fresh rosemary growing nearby your desk or home office.

- Eat blueberries: several studies have touted the memory-enhancing effects of blueberries and even just blueberry juice. One long-term study of nurses’ eating habits found that those who ate the most blueberries and strawberries delayed their memory decline up to 2.5 years compared to other nurses of the same age. The great thing about this research is that it showed just a couple of servings of berries per week were enough to make a difference.

- Meditate: It’s still fairly debatable whether we can seriously increase our working memory, but some studies have shown it’s possible. In particular, meditation and mindfulness-training (training to improve focusing abilities and attention span) have proven to increase working memory. Meditation appears to improve our abilities to block out external influences and ignore, or calm, the voices in our heads, which could leave room for greater working memory capacity.

I still have a bad memory. But at least I have some ideas for how I can improve it, now. I’ve just finished stocking up my fridge with berries, so it must be time for another coffee.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.