A team of scientists from the University of Washington and Carnegie Mellon University have developed a method by which three people can play a Tetris-like multiplayer decision-making game together using only their minds.

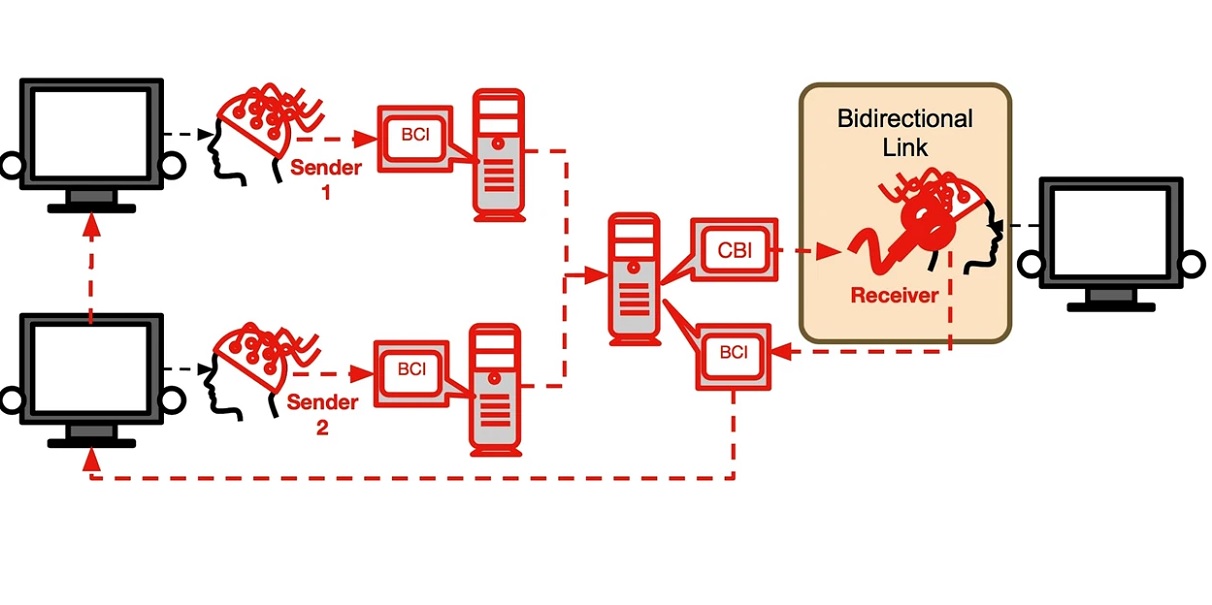

Researchers, Linxing Jiang, Andrea Stocco, Darby Losey, Justin Abernethy, Chantel Prat, and Rajesh Rao, created the interface, dubbed BrainNet. It’s “the first multi-person non-invasive direct brain-to-brain interface for collaborative problem solving,” according to their reseasrch paper. It allows three people in separate rooms to, essentially, network their brains and work together.

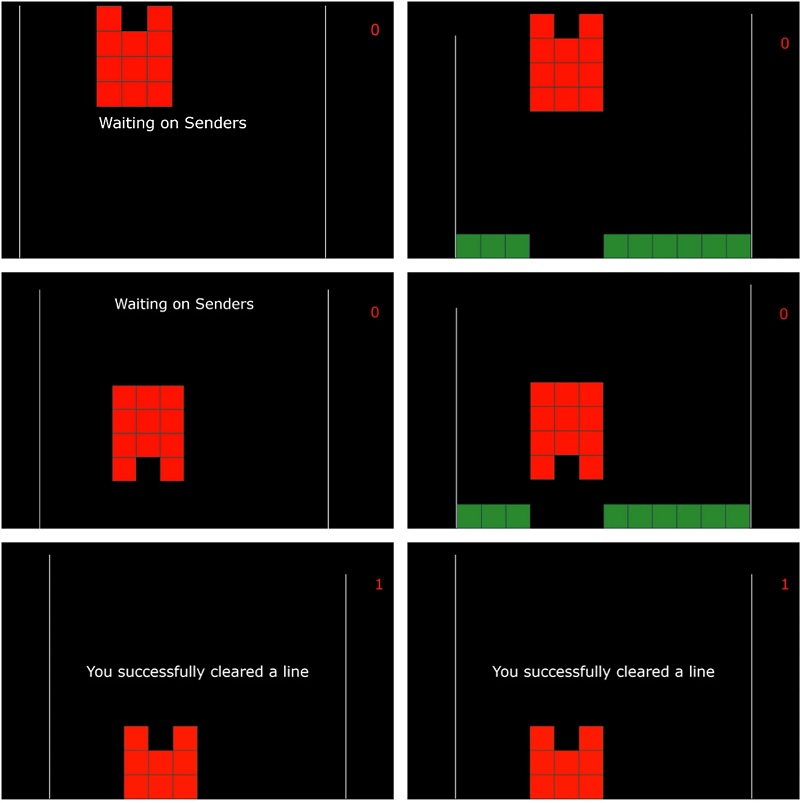

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the interface, the team came up with a new twist on the old Tetris game. Players in Tetris are tasked with manipulating falling blocks in order to form lines at the bottom of their screens. In the scientist’s version, three players are split into two senders and one receiver.

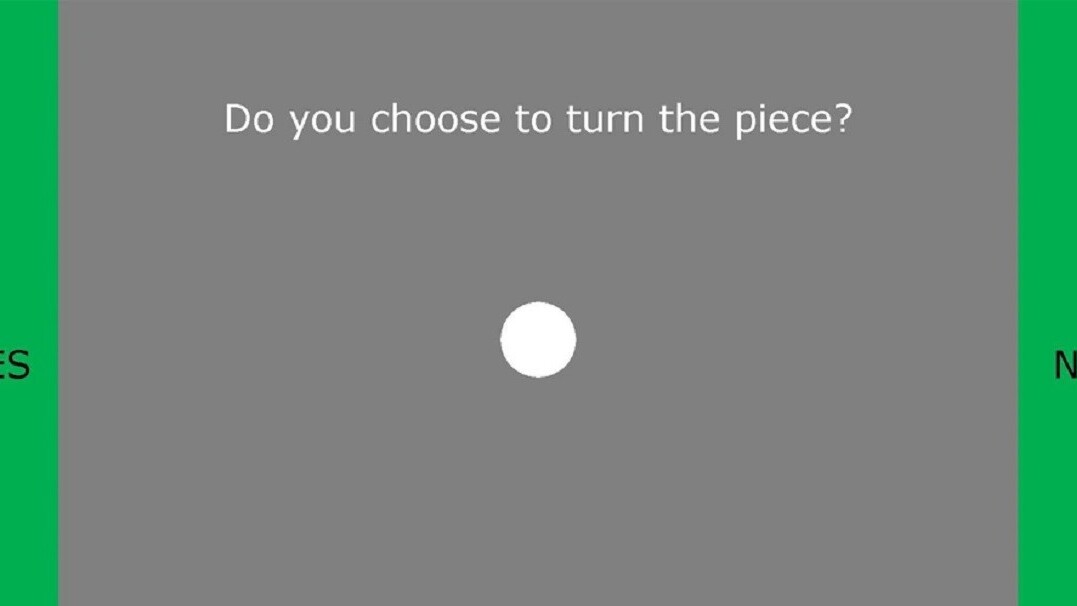

The receiver is the only player that can actually manipulate the falling blocks, but they can’t see the bottom of the screen to tell whether the pieces need to be rotated. The senders can see the bottom of the screen, but they can’t manipulate the blocks. Thus, the senders are tasked with observing each piece and then answering the question “should this block be rotated?”

Since humans don’t have the inherit ability to transmit their thoughts to one another, the researchers got creative. They presented the senders with the options for “yes” and “no” on the screen and asked them to concentrate on the correct answer. The options on the screen pulsed with light at different frequencies. This allowed an EEG headset device to determine which answer the sender was concentrating on by measuring their brain response.

The system then transmitted that information over the internet to a device that flashed a light in the receiver’s eye indicating which answer had been chosen. Finally, the receiver chooses a final answer by concentrating on “yes” or “no” in the same way the senders did.

The researchers then fudged the experiment a bit by flipping one of the sender’s answers to see if the receiver would catch on and become savvy to the fact that one of the senders was getting things wrong.

According to the paper:

Specifically, for each session, one Sender was randomly chosen as the “Bad” Sender and, in 10 out of sixteen trials, this Sender’s decision when sent to the Receiver was forced to be incorrect, both in the first and second round of each trial … We found that like conventional social networks, BrainNet allows Receivers to learn to trust the Sender who is more reliable, in this case, based solely on the information transmitted directly to their brains.

There’s a veritable cornucopia of implications for this technology. The researchers posit that BrainNet could scale to enable a global brain-to-brain network. This could lead to nearly frictionless collaboration between humans – like a social network for brains.

The team also hypothesizes humans using these kinds of interfaces could learn to filter out mental “noise” from bad actors — possibly by developing an instinctual method for detecting that something’s off when people intentionally concentrate on an incorrect answer.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.