It is a widely-known fact that censorship is rampant in China, as the government seeks to crack down on dissent within the massive country especially on social media websites.

Recently, after a former high-ranking official Bo Xilai was charged with bribery, embezzlement and power abuse, China’s censors went into overdrive on Twitter-like microblogging platform Sina Weibo, with comments that criticized the Communist Party or expressed sympathy for Bo being taken down.

Yet in some cases, social media users manage to get away with criticizing the government. How does this work?

China aims to block out collective talk

A research paper written by a group of students at Harvard University released yesterday gives more insight into the whole censorship process within China. It suggests that China could be censoring as many pro-government comments online as criticism.

Besically, Chinese censors allow for government criticism, but silence collective expression. Censorship in China is not only about weeding out anti-government sentiment — censors often also remove posts supportive of the government if they concern collective action events. The research paper notes:

Our results offer unambiguous support for, and clarification of, the emerging view that criticism of the state, its leaders, and their policies are routinely published whereas posts with collective action potential are much more likely to be censored… We are also able to clarify the internal mechanisms of the Chinese censorship apparatus and show that local social media sites have far more flexibility than was previously understood in how (but not what) they censor.

One particular example of how Chinese censorship works could be the June 4th incident aka the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 — when censors block out key words every year on the anniversary date. This means even if a social media user expresses support for the government, the post will still get deleted for simply mentioning the incident.

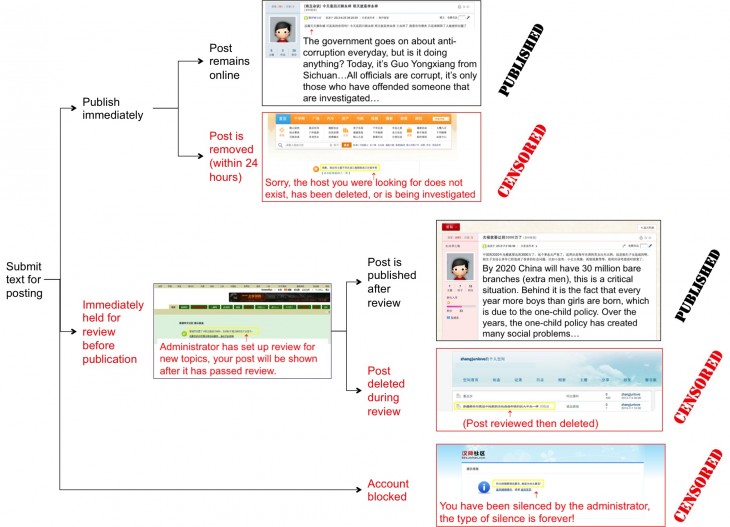

The research paper notes that Chinese Web policing is mainly carried out via two different methods: censorship and review. The former is a publish-first-censor-later process, while the latter involves a more careful (and less free) review-first-maybe-publish-later process.

First of all, the censorship process starts when you write and submit a blog or microblog post on a social media website. The post is then either published immediately or held for review. If it gets published straightaway, it will be manually read by a censor within about 24 hours and then either remains online or gets removed from the site.

The three authors — Gary King, Jennifer Pan and Margaret Roberts — selected 100 social media sites in their study, including 97 of the top blogging sites in the country, representing 87 percent of blog posts now on the web, as well as the top three Twitter-like microblogging platforms — Sina Weibo, Tencent Weibo and Sohu Weibo.

They found that “automated review affects a remarkably large portion of the social media landscape in China”. Out of the 100 sites, 66 reviewed at least some social media submissions, while 41 percent of all individual social media submissions from the 100 sites are put into review.

“Review therefore affects large component of intended speech in China and clearly deserves more systematic attention from researchers,” the paper notes.

In their study, the researchers were also surprised at the huge variety of technical methods by which review and censorship can be conducted:

We first notice that not all websites have automated review turned on, and that the method of censorship varies enormously by website. This is consistent with what we learned from creating our own social media site, where the software platform not only allows the option of whether to review, but also offers a large variety of choices of the criteria by which to review.

They note that it is likely because the government is (perhaps intentionally) promoting innovation and competition in the technologies of censorship, and it could also be a means of control as well — after all, it is easier to keep

people away from a fuzzy line than a clearly drawn one.

Pro-government posts also get censored sometimes

Interestingly enough, the research paper found that sometimes, more pro- than anti-government posts are reviewed in certain topics. Why does this happen?

Basically, government-controlled social media sites carry out the review process the most, followed by social media sites that state-owned enterprises control, and then privately-owned sites — which tend to publish first then make censorship decisions. The authors note that this is likely due to harsher penalties on government sites for letting offending posts go through.

However, with an automated review process, this means that posts with certain key words, whether pro- or anti-government, get deleted all the same despite the context. For example, the research paper noted that more pro- than anti-government posts were reviewed in the Corruption Policy topic, probably because the reviewed pro-government posts used the word corruption more frequently than anti-government posts — even though corruption was used in the context of praising how the new policy would strengthen anti-corruption efforts. The paper notes:

It thus appears that the workers in government-controlled web sites are so risk adverse that they have marshaled a highly error prone methodology to try to protect themselves. (However), they apparently know not to take this review methodology very seriously as, whether it is used or not, the manual process of review is still used widely and, our results show, do not affect the causal effect of collective action events on censorship decisions.

Ultimately, the paper notes that in China, regime stability is the assumed end goal. The government just does not want any mention of undesired political topics, no matter whether anti-government or supportive of the party.

Headline image via Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.