The prevailing view of artificial intelligence is that some day machines will help us reach better decisions than we can make on our own, improving our lives.

This view presumes that we trust the organizations that use AI to provide us with products and services. But that is a faulty assumption, because most will not have our best interests in mind.

Some scientists, many science fiction buffs, and a lot of the public believe perfect forms of AI — machines in likeness of humans that can actually understand the world, reason about it, and make perfect decisions — are just around the corner. Others, including me, believe it will take decades to achieve. And some scientists believe we will never achieve strong AI.

Those who believe in the wonders of a lofty kind of AI are eagerly awaiting its arrival, but in the meantime what we have is an interim step called machine learning algorithms, or weak AI, a seemingly intelligent machine that can perform a narrow task as well or better than humans, but is incapable of going beyond the rules that govern it. And they, in particular, pose a threat to our interests.

We have all heard of these algorithms, because they have been a key to the success of such tech giants like Google and Facebook.

In their simplest form, they are sets of instructions that a computer uses to solve a problem. As any of us who use Facebook know, they can be refined again and again to yield a better solution. But for whom?

The threat from algorithms boils down to a simple question: Do they benefit the organizations that develop them, those who use the organizations’ products and services, or — as the organizations contend — both parties?

More and more of us believe the answer is: The main beneficiaries of these algorithms and services are the organizations that develop them.

But the issue goes beyond algorithms’ main beneficiaries. Another question to ask is: Are they causing harm? And many would say yes.

Those who are salivating for perfect AI believe it will give them a range of choices they could not get otherwise — and that additional choices are a good deal because they will increase their ability to achieve a better life.

But more people who use the products and services of algorithm-based Internet companies are coming to the realization that instead of increasing our choices, algorithms narrow them.

Take online news feeds, for example.

Most journalists have an insatiable curiosity and want a broad range of news each day.

But an elderly journalist with whom I am acquainted has come into contact in quite a real way with the so-called filter bubble, realizing that both his Yahoo and his Google news feeds are giving him a very narrow menu of stories each day. He feels as though they are censoring him.

Like many people, he cannot wait to learn about the latest Trump administration outrage. He also has a keen interest in renewable energy, reading every new wrinkle he can find about it.

He discovered a couple of years ago that Yahoo in particular was filling his news wall with stories about Trump, renewable energy, a few other topics — and nothing else.

It was obviously where this was coming from, he said. Yahoo’s algorithm identified the subjects that he was most interested in by his reading habits, and gave him more of the same instead of the broad range that he wanted, a self-reinforcing spiral until his feed was reduced to just a few topics.

He is frustrated because he is wondering what news he is missing that is not on his Yahoo wall — stories about business, culture, art, travel and other topics that he wants to know about.

This inadvertent narrowing of this journalist’s worldview not only fails to quench his thirst for news beyond Trump and renewables, but it may also be impacting his career. What subjects besides American politics and alternative energy might he be covering if he knew about them?

This journalist’s story is a simple example of algorithms narrowing people’s choices instead of broadening them. If those narrowed choices are impacting his career, then algorithms are not neutral information facilitators, but rather causing harm.

This particular journalist knew algorithms were narrowing his choices, although he did not know specifically what to do about it. But what about the millions of people who do not know?

Consider this scenario:

You are having a bad day. You had a fight with your boss, your wife is grumpy, and the starter in your car conked out.

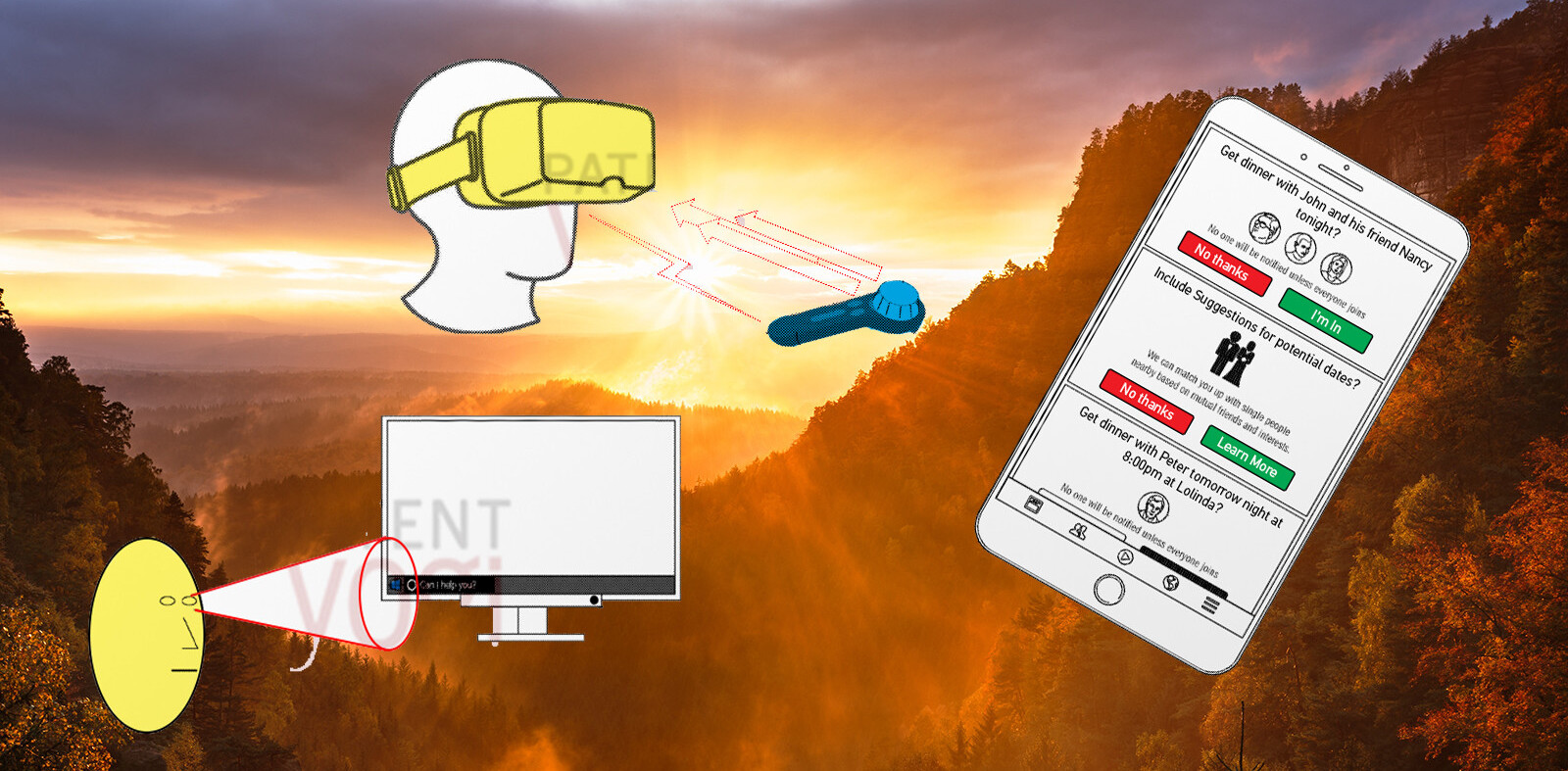

Google has been reading your online communications and monitoring your vital signs and stress levels during the day, and knows that you are out of sorts. When you come home, it changes the smart lighting in the house to something that is soothing and turns on some calming music for you.

Naturally you start to feel better. Is it because you have returned to the comfort of your home, because your wife just kissed you, because you popped open a beer, or because of the different background that Google has created for you?

The moment we are unable to recognize whether we feel better because of pleasantries arising from the decisions we made ourselves or because of an artificial environment that an algorithm has created, we are in big trouble. Because at that moment, instead of technology working for us by expanding our world, it has exerted its control to narrow it.

Machine learning on the Web potentially manipulates and constricts our worldview. In the real world, though, it manipulates our bodies and physicality, narrowing the boundaries of our world.

Right now, we may need some kind of filtering on the Internet, because there would simply be too much information for a human to process otherwise and our journalist might be a mere victim of a necessity. But now we are entering a new area where all objects around us are also becoming more and more connected and digital. If we start unnecessarily applying the same design principles and algorithms to the real world, then we start seeing much broader and dangerous effects.

How do we prevent algorithms from exerting such potentially harmful control over us?

We can start by understanding how they work so that we can ward off their negative effects.

About three decades ago, people alarmed about the negative effect that slanted news could have on us started what is called the media literacy movement. The idea was to educate people about who was creating news stories and how the stories could be slanted to create impressions that the authors wanted. That movement is continuing — and given the surge in today’s unbalanced and fake news, it is needed more than ever.

We need to start a similar educational effort to let people know how algorithms impact their thinking, their habits — and basically, their lives. A key thrust of this effort would be encouraging people to question the notifications, suggestions and other algorithm-generated information they receive online. Who is sending the messages, why, and what negative impact could they have on me?

What causes algorithms to send these messages is usually very simple, and people could understand easily if they are educated about it properly.

Although this effort should cover all ages, it is important that it start with even very young children.

In conjunction with this educational effort, we should press tech companies to formulate codes of ethics governing their algorithm-related activities.

It might even be wise to consider rules governing the intersection of technology products and society. Some of you may think that is far-fetched. I am not saying I do not trust the individuals behind such algorithms. These programmers are trying to do good to improve people’s lives. The problem is that there is a fallacy here, whereby attempting to improve people’s lives through machine learning actually leads to the opposite. We cannot blame these individuals as, to them, it might well appear as though their algorithms are enhancing our lives – and the metrics might even look that way (i.e. 30 percent of our users are now using feature X, saving them Y time!). So instead of blaming them, I believe that we must start a discourse with them, and I would like to see a wide-ranging discussion of this issue – an algorithm-literacy effort.

Machine-learning algorithms will become more refined as time goes by. In my book, this means they will become an increasingly unrecognized threat to our ability to make our own choices.

For this reason, the sooner we start educating the public and the people who create these algorithms about these issues, the better.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.