The Internet of Trucks is here.

Or, to be, more specific: the internet of tarpaulins. Industrial textile company Sioen is currently developing smart truck tarpaulins that notify security when someone tries to cut through it.

It’s one of three new innovations created for the project PASSAnT, a Dutch-Belgian initiative by Interreg to deal with crime in Dutch and Belgian harbors. With an increasing number of illegal immigrants trying to make their way to the UK, people smuggling has drastically increased in harbors near the Dutch-Belgian border.

New Calais

The Dutch city of Moerdijk, already dubbed “the new Calais” by some, particularly struggles with stowaways. Dutch police caught 500 people in 2015, and in 2016 this number had more than doubled to 1280.

This year’s statistics have not yet been published but according to Leon Verver, the number is still growing. Verver is policeman and director of the Dutch Institute for Technology, Safety & Security (DITSS).

“Apparently, these people — most of them Albanians — still believe the UK is their best bet. So they wait until nightfall to climb into parked trucks near the harbors.”

It’s not just an issue of illegal transport immigration; Dutch and Belgian harbors also deal with smuggling of drugs and explosives, as well as theft of goods.

Smart fences

PASSAnT aims to tackle each of these crimes, using new technologies. Besides intrusion-proof tarpaulins, interactive fences and smart camera software are also in the making. By the end of next year, the pilot should be up and running.

“The fence contains sensors that are similar to microphones; they don’t just detect vibrations but also analyze them,” explains Verver.

“So when someone accidentally touches the fence, the system won’t notify the alarm room. But when this happens three times in a row, it does. The same goes for weather conditions: the sensors ‘understand’ the difference between a stormy day and someone climbing the fence.”

While climbing fences and cutting through tarpaulins are pretty obvious indicators of crime, other behaviors are more difficult to identify. That’s where image analysis software comes in.

“Suppose you’re walking along the fence and stop a few times. That behavior makes sense if you’re walking your dog. If you’re by yourself and carry a large backpack, on the other hand, it’s more suspicious.”

The image analysis software is based on an algorithm that makes sense of such behaviors (like stopping a few times) and visual clues (like wearing a backpack). Think of it as a point system: each suspicious element earn a point. When a certain threshold is reached, the system will notify security.

“When that happens we question this person over the audio system or send someone by to check it out,” Verver continues.

Backpacks yes, skin color no

What does the algorithm look for? Verver can name a few ‘suspicious’ elements but doesn’t know the entire list. He ensures me visual features like skin color are not used for analysis — which would also be illegal — but as mentioned before, specific types of clothing do serve as markers.

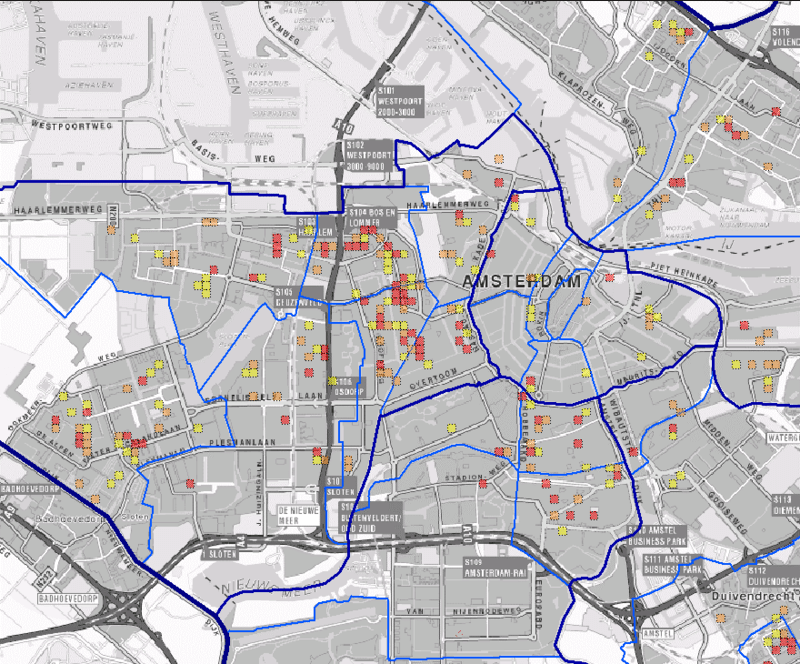

The Dutch government is betting big on data science to predict crime. Several cities make use of CAS (Criminal Anticipation System), a “heat mapping” system that identifies criminal hotspots based on previous crimes and demographic data.

At the same time, the police are running big data pilots to decrease nightlife violence in Eindhoven, curb burglaries in Rotterdam, and catch pickpockets in Roermond.

Thieving gangs

That last project, called “Sensing,” uses similar smart camera software but looks for different ‘suspicious’ aspects, mostly targeting Eastern European criminals. The city of Roermond, close to the Dutch-German border, struggles with thieving gangs from that region.

The system combines wifi-tracking (for example, to detect Romanian phone numbers), number plate analysis (German rental cars are suspicious), and behavioral image analysis (someone lingering at a street corner) to provide notifications to police officers in the area: This person or group of people might be up to no good.

“In that case, police officers can ask for their ID and check their bags,” says Verver.

Of course, if this group turns out to be a bunch of Romanian tourists enjoying a day of shopping, the conversation will be a short one. But still, the fact that someone is more likely to be flagged because they happen to be Eastern-European raises eyebrows.

Verver understands these concerns but adds that it’s not just the Romanian phone number or car plate that sets off the system — there are a lot of different signals.

“So the chance that an innocent person accidentally ticks all or at least many of these boxes is rather small,” he continues.

Does it work?

What doesn’t help when addressing privacy concerns, is that’s it’s still too early to measure the effectiveness of predictive policing. In many countries besides the Netherlands, the jury’s still out on whether it works. In the US, studies exploring “PredPol”, one of the main providers of predictive policing software, show varying results.

And even if predictive policing is proven to be effective, tech optimists like Verver will still need to conquer the hearts and minds of police officers in the street.

A Dutch study exploring how police officers feel about using predictive software CAS shows the response is lukewarm at best. The interviewees said the software “didn’t tell them anything they didn’t already know” and that “it’s a waste of resources to mainly focus on CAS areas.”

To be fair, some of these concerns can probably be tackled with more education. One of the interviewed officers mentioned they “simply did not believe predicting crime was possible” without offering any valid arguments as to why not.

The Dutch government recently announced their plans to spend an extra annual €64 million on big data training for police, so in the future, they might have a better understanding of what to expect from data analysis.

Verver isn’t worried. Give these officers some time to get used to this new reality, he says. “Policing will become increasingly tech-based and right now, not everyone is ready for that change. But once we can show them this will make their jobs easier and the streets a safer place, I’m positive they’ll come around.”

Now that much crime has gone digital, the Dutch police need tech talent more than ever. Check out the various tech jobs they have to offer.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.