Technology has simplified the movement of money so much that people and businesses can send funds anywhere in the world, instantly, but tech’s rapid advance has also brought new ways to launder cash.

In fact, the United Nations warns this rise of “megabyte money” makes curbing the transfer of illicit funds more urgent than ever.

Globally, estimates suggest between $800 billion and $2 trillion in laundered money flows through the financial system every year, and an overwhelming majority of it goes undetected. The Netherlands alone sees $16 billion in criminal money flowing through its financial system.

Zooming out to Europe as a whole, the European Commission found just 1% of an estimated $190 billion in laundered funds were successfully confiscated between 2010 and 2014.

To help uncover money laundering across the EU, ABN AMRO teamed up with ING, Rabobank, Triodos Bank, and de Volksbank to share all of their customers’ payment transactions in an initiative creatively dubbed Transaction Monitoring Netherlands (TMNL).

Indeed, thanks to a new Dutch law allowing banks to share limited customer data, 12 billion transactions per year are now set to be trawled by algorithms built to detect suspicious financial activity, equating to 33 million per day.

Through TMNL, the five banks will look to jointly monitor their transactions for signals of money laundering and terrorist financing; ‘strength in numbers’ the rallying cry.

ABN AMRO takes a holistic approach to detecting laundered money

Analyzing financial data with AI, advanced analytics, and machine learning technologies plays a major role in that task, sure, but so do manual investigations and other forms of cooperation between banks.

“It’s not only about looking at information (transactions), it’s also about putting the right questions to customers,” said ABN AMRO’s managing director of financial crime detection Robin de Jongh at TNW2020.

“So, being curious, but also holding a neutral way of thinking towards the customer, and not assuming that everyone is a crook or criminal,” he added.

To stay ahead, ABN AMRO runs its own Detecting Financial Crime Academy to help investigators sharpen their skills.

De Jongh: “We employed 25 Sherlock Holmes-types to detect financial crime via intelligence-led analysis on money laundering schemes and modus operandi.”

Tech won’t stop, so staying ahead of the curve is crucial

On the other hand, ABN AMRO’s Ivich Hoffman likened her bank’s method of detecting laundered cash to making the perfect cocktail. Hoffman, Product Owner Connect for Detecting Financial Crime, was one of the panelists during TNW2020.

“In my opinion, there are three main ingredients: data, advanced analytics, and cooperation between banks,” said Hoffman, before adding that one of ABN AMRO’s slogans is “data is at the heart of everything.”

The three ingredients affect more change as the sum of their parts. Data, for one, needs to be as broad as possible. “If we only use our data for one bank, does the crime stop at the door of that bank? Or is it better to see data of all banks together?” asked Hoffman.

(We talked about this in more detail in the podcast ‘How banks detect money laundering.’ You can listen to it here.)

There’s also the need for targeted approaches when analyzing potentially suspicious data (this is the advanced analytics part). For example, if one investigates all “Politically Exposed Persons” for potential involvement in money laundering, many suspicions will be proven correct. But this isn’t always the case.

“Therefore, it’s much more effective to create models,” said Hoffman. “For example, within ABN AMRO, we have used a data science model to detect potential human trafficking, and we are using artificial intelligence and machine learning models to detect unknown unknowns.”

Banks are gate-keepers that must work together

In some sense, the third ingredient is the most crucial: co-operation between banks, and that’s exactly where TMNL comes in.

The way ABN AMRO sees it, banks are “gatekeepers of the financial system,” and so those institutions have a statutory duty to protect the integrity of that system.

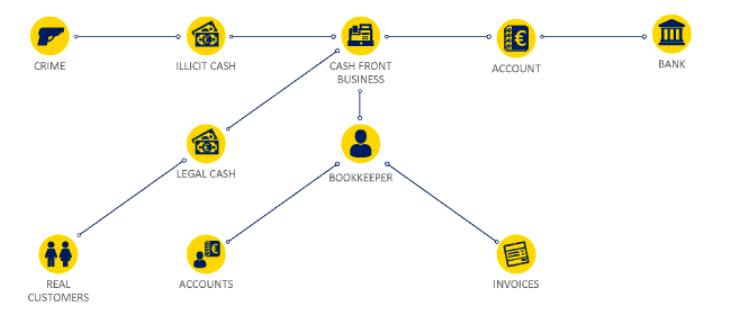

Criminals and their financial networks, however, are considerably complex. Those handling illicit funds often bank with a number of banks simultaneously, and may bounce between them in a bid to hide their dodgy dealings — making it even more critical for banks to share their algorithmic firepower.

“Do you think it’s effective for banks to develop all these models on their own? Or is it better to cooperate?” asked ABN AMRO’s Hoffman at TNW 2020. Personally, she’s leaning towards the latter. “In my opinion, the best way to detect financial crime is in cooperation with other banks. And that’s what we have started.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.

Whatever your specialism, with ABN AMRO your talent and creativity will help build the bank of the future. Learn more about their exciting tech job opportunities.