The humble honeybee can use symbols to perform basic maths including addition and subtraction, shows new research published today in the journal Science Advances.

Despite having a brain containing less than one million neurons, the honeybee has recently shown it can manage complex problems – like understanding the concept of zero.

Honeybees are a high value model for exploring questions about neuroscience. In our latest study we decided to test if they could learn to perform simple arithmetical operations such as addition and subtraction.

Addition and subtraction operations

As children, we learn that a plus symbol (+) means we have to add two or more quantities, while a minus symbol (-) means we have to subtract quantities from each other.

To solve these problems, we need both long-term and short-term memory. We use working (short-term) memory to manage the numerical values while performing the operation, and we store the rules for adding or subtracting in long-term memory.

Although the ability to perform arithmetic like adding and subtracting is not simple, it is vital in human societies. The Egyptians and Babylonians show evidence of using arithmetic around 2000BCE, which would have been useful – for example – to count live stock and calculate new numbers when cattle were sold off.

But does the development of arithmetical thinking require a large primate brain, or do other animals face similar problems that enable them to process arithmetic operations? We explored this using the honeybee.

How to train a bee

Honeybees are central place foragers – which means that a forager bee will return to a place if the location provides a good source of food.

We provide bees with a high concentration of sugar water during experiments, so individual bees (all female) continue to return to the experiment to collect nutrition for the hive.

In our setup, when a bee chooses a correct number (see below) she receives a reward of sugar water. If she makes an incorrect choice, she will receive a bitter tasting quinine solution.

We use this method to teach individual bees to learn the task of addition or subtraction over four to seven hours. Each time the bee became full she returned to the hive, then came back to the experiment to continue learning.

Addition and subtraction in bees

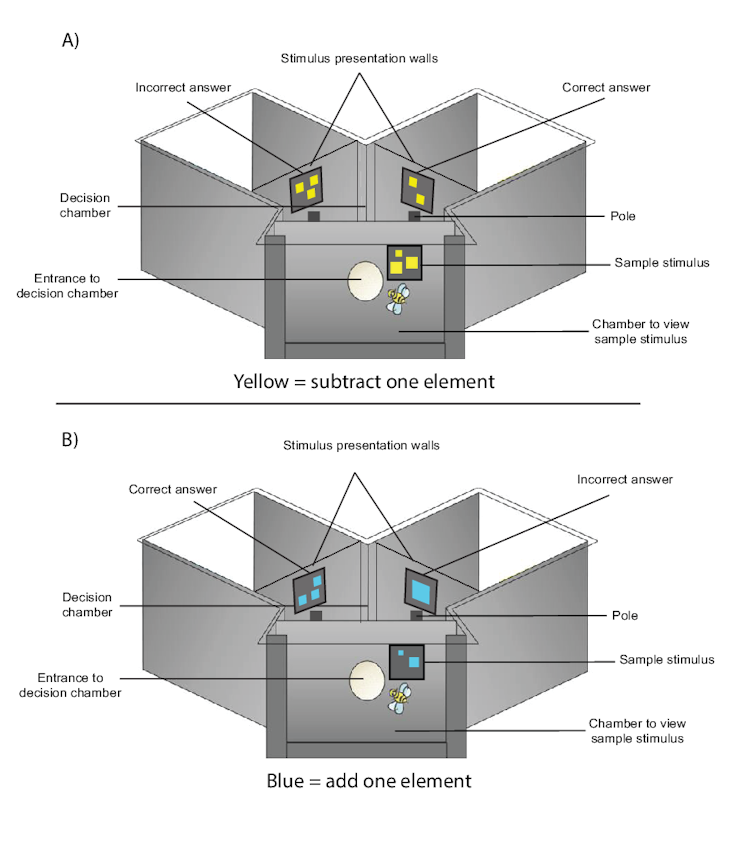

Honeybees were individually trained to visit a Y-maze shaped apparatus.

The bee would fly into the entrance of the Y-maze and view an array of elements consisting of between one to five shapes. The shapes (for example: square shapes, but many shape options were employed in actual experiments) would be one of two colors. Blue meant the bee had to perform an addition operation (+ 1). If the shapes were yellow, the bee would have to perform a subtraction operation (- 1).

For the task of either plus or minus one, one side would contain an incorrect answer and the other side would contain the correct answer. The side of stimuli was changed randomly throughout the experiment, so that the bee would not learn to only visit one side of the Y-maze.

After viewing the initial number, each bee would fly through a hole into a decision chamber where it could either choose to fly to the left or right side of the Y-maze depending on operation to which she had been trained for.

At the beginning of the experiment, bees made random choices until they could work out how to solve the problem. Eventually, over 100 learning trials, bees learnt that blue meant +1 while yellow meant -1. Bees could then apply the rules to new numbers.

During testing with a novel number, bees were correct in addition and subtraction of one element 64-72 percent of the time. The bee’s performance on tests was significantly different than what we would expect if bees were choosing randomly, called chance level performance (50 percent correct/incorrect)

Thus, our “bee school” within the Y-maze allowed the bees to learn how to use arithmetic operators to add or subtract.

Why is this a complex question for bees?

Numerical operations such as addition and subtraction are complex questions because they require two levels of processing. The first level requires a bee to comprehend the value of numerical attributes. The second level requires the bee to mentally manipulate numerical attributes in working memory.

In addition to these two processes, bees also had to perform the arithmetic operations in working memory – the number “one” to be added or subtracted was not visually present. Rather, the idea of plus one or minus “one” was an abstract concept which bees had to resolve over the course of the training.

Showing that a bee can combine simple arithmetic and symbolic learning has identified numerous areas of research to expand into, such as whether other animals can add and subtract.

Implications for AI and neurobiology

There is a lot of interest in AI, and how well computers can enable self learning of novel problems.

Our new findings show that learning symbolic arithmetic operators to enable addition and subtraction is possible with a miniature brain. This suggests there may be new ways to incorporate interactions of both long-term rules and working memory into designs to improve rapid AI learning of new problems.

Also, our findings show that the understanding of maths symbols as a language with operators is something that many brains can probably achieve, and helps explain how many human cultures independently developed numeracy skills.

This article is republished from The Conversation by Scarlett Howard, PhD candidate, RMIT University; Adrian Dyer, Associate Professor, RMIT University, and Jair Garcia, Research fellow, RMIT University under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.