What a nuisance is a faulty memory. How many times have you forgotten where you parked the car? A few years ago, probably as a sign that my retirement was overdue, I spent literally half a day trying to find my car at a major New York airport. Fortunately, I am not alone. When people find out I am an expert on memory, the first thing they ask me is normally whether I can help them be less forgetful.

Indeed, excessive forgetting is a major problem, but “normal” forgetting is actually necessary. After all, it is more crucial to remember what is important right now than to remember everything. There’s no point in remembering the phone number of the house you lived in 10 years ago – that may in fact block your memory for your current phone number.

But exactly how the brain forgets unnecessary memories has long been unclear. Now a beautiful and rather exhaustive series of studies, just published in Science, offers a clue.

Research does indeed show that, in order to remember what is important, we need to forget what isn’t important. This can happen at two levels in the brain, a “cleaning” of irrelevant information as we retain and consolidate our memories, and a “blocking” of irrelevant information when we try to retrieve a memory. The positive effect on memory of blocking irrelevant information has been known since the 1950s.

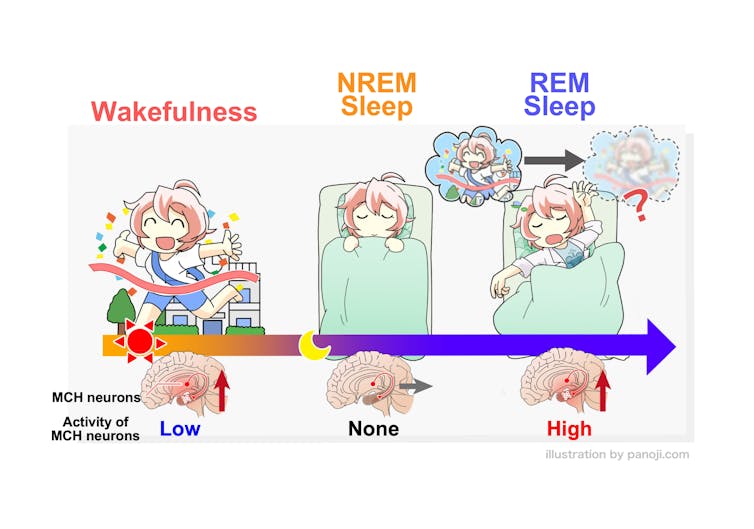

The new study, which was carried out in mice, seems to finally reveal the secret mechanisms of forgetting during retention of memory. The authors claim that forgetting is due to the activation of specific “melatonin-concentrating hormone (MCH) neurons” located in the brain’s hypothalamus, which is involved in releasing hormones. We know that melatonin affects sleep – and MCH neurons are indeed involved in the shift between the two main sleep cycles: NREM to REM (REM sleep commonly associated with dreaming).

The authors demonstrate that forgetting happens only during retention (not when we encode or retrieve memories), and that sleep is the period of the day when MCH neurons clean the memory of all the irrelevant clutter. They obtained the results by injecting chemicals into the brain of mice in order to inhibit these very neurons. Amazingly, the mice performed better on two specific memory tasks as a result – recognizing new objects and a fear conditioning test (this involves making association between stimuli and their adverse consequences).

What’s more, when the researchers completely removed these neurons from the brain, the mice’s memory also improved, over the long term. On the other hand, a boosted activity of these neurons instead hindered the mice’s memory performance. The researchers therefore argue that the neuronal process may one day be used to treat memory problems.

This finding, if true and confirmed by other studies, represents a major breakthrough in understanding a fundamental memory mechanism. The methodology is rigorous and results convincing. There are some caveats though. How can we be absolutely sure that these neurons are involved in cleaning out irrelevant information in particular, rather than just impairing memory performance?

It seems that MCH neurons, when activated, just impair memory – and not necessarily with a good effect. This is important: the results do not say much about the positive role of forgetting during retention. In addition, whose memory are we talking about here? Mice memory – and necessarily so, given the highly invasive nature of most of the reported experiments. While animal models are indispensable for memory studies, it is too early to extend these findings to human memory.

For example, in humans the role of sleep in memory is still unclear. Also, forgetting occurs during retrieval of memories too and that is not explained by this new research.

Nevertheless, the new study does show for the first time that MCH neurons are strongly involved in making memory worse. That said, while we are on an exciting track thanks to this research, it is highly unlikely that we can improve human memory for a parked car by simply inhibiting a few neurons.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Giuliana Mazzoni, Professor of Psychology, University of Hull under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.