It’s been a big month for DNA profiling.

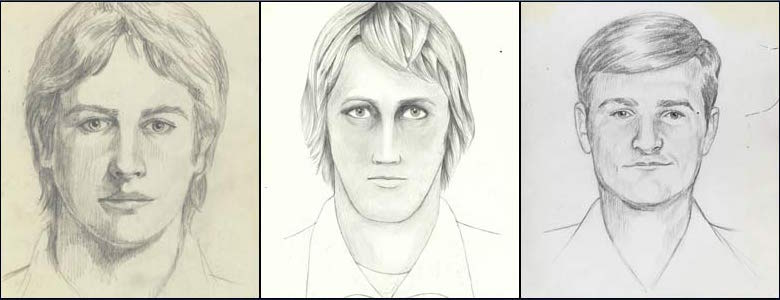

A few weeks ago, after over 30 years, the American police finally arrested the “Golden State Killer.” The suspect, now 72 years old, allegedly committed a series of horrific murders and rapes in California in the 1970s and ’80s.

How they caught him? By checking crime scene DNA against a public genealogy website.

Dutch Detective Chief Superintendent Mark Wiebes read the story, obviously. But, he quickly adds: This would not have been legally possible in the Netherlands.

“In long-drawn, heart-wrenching cases like this, it’s tempting to collect and analyze as many DNA samples as possible. But that doesn’t make it right.”

To quickly explain the privacy concerns at hand: The American police officers involved used DNA samples from the website GEDmatch, a website that lets users look up information about their genetic background by matching their DNA against publicly available DNA profiles. The Golden State Killer’s DNA partially matched one profile in the database — which belongs to a relative of the killer — and led the police to the suspect.

Wiebes has always been opposed to the installment of a national DNA database that contains samples of the whole Dutch population, for which several bills were proposed in the past decade.

“We don’t need a bigger net to become better at catching criminals. We need to become better at interpreting the data we already have.”

Ruling out who didn’t do it

The answer to becoming better, faster, and more efficient lies in technology, according to Wiebes. Besides Detective Chief Superintendent, he’s also Deputy Chief Innovation Officer, which means he closely follows technical developments within forensic science.

“There is so much information that can be derived from DNA now”, says Wiebes. “Skin color, hair color, the color of someone’ eyes. The shape of their skull. Whether or not they have freckles. Where their ancestors are from.”

To be clear: It’s not as if forensic scientists analyze DNA samples, create physical profiles and then use those profiles to prove that someone is guilty. DNA evidence can never be used to convict a perpetrator unless there’s a full match with someone in the Dutch forensic DNA database — which contains DNA from people previously convicted — and even in those cases, other evidence is needed as well.

What it can do is rule out suspects who didn’t do it, preferably in an early stage of the investigation, which obviously saves time, money and resources.

This approach to DNA-profiling — excluding suspects instead of including them — helped to reopen a Dutch cold case that had been on the shelves since the early 90s: the rape and murder of then 19-year old Milica van Doorn. Using new forensic technology that pinpoints someone’s ancestry, the crime scene DNA sample revealed that it belonged to someone of Turkish descent.

This new information allowed the police to set up a small-scale kinship research in the area where Van Doorn was found; only men with Turkish roots were asked to participate. Although the man who’s currently the main suspect refused to offer a DNA sample, he was identified because one of his relatives did participate in the study.

In addition to the various traits that can be identified using DNA analysis, the process will soon be less time-consuming. Normally, it takes the Dutch Forensics Institute (NFI) at least six hours to analyze a sample.

Now, the Dutch police is looking into ways to analyze DNA themselves, using a new technology that lets them identify certain traits within two hours. “Quick DNA determination,” as Wiebes calls it, could help filter out certain suspects straight away.

Matching profiles on the go

One possible scenario where this could be useful, is when detectives are shadowing a certain suspect.

“By secretly collecting some of his DNA — he throws out a cigarette bud, or plastic cup — we could match profiles on the go.”

Quick DNA determination will also advance large-scale kinship studies such as the one currently being conducted in an attempt to solve the murder of 11-year old Nicky Verstappen, killed in 1998. Twenty thousand men were asked to donate a DNA sample.

“Right now, we need about a year to collect and analyze all the samples manually. If we could outsource all of this to computers, we could process more samples in a shorter timespan. And if we find a match in, let’s say, the fifth batch of 200 samples, we can immediately call off the search and don’t need to burden other men with donating their DNA.”

Less DNA, more contamination

In addition to DNA-analysis becoming less time-consuming, scientific developments have made it possible to identify very small quantities of DNA. Someone touching a door handle while leaving some skin cells can be enough to identify someone’s genetic fingerprint.

But there’s a downside: The door handle probably contains the skin cells of many different hands — and people. Even worse, the second hand touching the handle might collect skin cells by the first person and spread them somewhere else.

The smaller the DNA sample, the higher the chance of contamination, says Wiebes.

“Look: if we find your skin cells underneath the victim’s fingernails, you’d better have a good alibi. If we find it on a table or door handle, however, it’s far less certain you are the one we’re looking for.”

Something similar happened during a recent murder case in Amsterdam, according to local newspaper Het Parool (in Dutch). During the investigation, the police collected several weapons by the suspected killer, Shurandy S. One of these guns contained the DNA of someone else: a 31-year old plant nursery owner who, as soon became clear, had nothing to do with the case. How his DNA ended up on the gun remains unclear, but he did spend five days in custody before his innocence was proven.

Solving this problem — establishing which DNA is relevant to a case and which isn’t — is one of the big challenges the police faces today. There are some promising research projects, however, that may fix this.

Currently, researchers at the NFI are looking into the chemical compound of fingerprints to determine when someone left it. Proteins tend to change under the influence of temperature changes or light. By interpreting these changes correctly, the researchers can determine how old these traces are. Although it will take five more years before this can be put to use, being able to establish when traces were left at the crime scene is obviously of great value for investigators.

Focusing on what we can see

Although not perfect, Wiebes firmly believes DNA forensics should play an even bigger role during investigations.

“Right now, our modus operandi is to first focus on tactics whenever we enter a crime scene: what has happened here? I think — and please note this is my personal opinion, I’m not speaking for the whole force here — we should start with focusing all our attention on traces of evidence: what do we see?”

Of course, knowing what to look for also doesn’t hurt in these cases. Another element that can still be improved, Wiebes says.

“In many cases, we already have the information we need — we just have trouble finding it. This is exactly why I’m pushing for the use of new technologies. Even with the best will in the world, my brain can’t compare 1500 cold cases containing 200 files each. A machine can. So it’s time we start harnessing those capabilities to our benefit.”

As much crime has gone digital, the Dutch police now needs tech talent more than ever. Would you like to fight crime with code? Then find your future job here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.