Two years ago, I discovered that I was on the autism spectrum. As I learned more about myself and the way my brain worked, I started to look at past experiences through the lens of this newly-found aspect. In this essay, I share some of what I’ve learned along the way about my successes, my failures, and many things that confused me in the past, notably in my experiences in the Wikimedia movement.

This is a picture of me taken when I was 4, in nursery school, the French equivalent of Kindergarten.

I don’t have many memories about that time, but my parents remember that, while I wasn’t usually enthused about going to school during the week, I would often ask to go on Saturdays, because most of the other kids weren’t there.

It wasn’t that I didn’t like them; it was because the school was much quieter than during weekdays, and I had all the toys to myself. I didn’t have to interact with other children, or share the pencils, or the room. I could do whatever I wanted without worrying about the other kids.

I didn’t know it at the time, but it would take me nearly 30 years to look back at this story and understand how it made complete sense.

Today

I’m now 32 years old, and a lot has changed. Two years ago, after some difficulties at work, my partner decided to share his suspicions that I might be on the autism spectrum. I knew little about it at the time, but it was a hypothesis that seemed to explain a lot, and seemed worth exploring.

Sure, the subject had come up before a few times, but it was always as a joke, an exaggeration of my behavior. I never thought that label applied to me. One problem is that autism is usually represented in a very uniform manner in popular culture. Movies like Rain Man feature autistic savants who, although they have extraordinary abilities, live in a completely different world, and sometimes aren’t verbal. The autism spectrum is much more diverse than those stereotypical examples.

After I started researching the topic, and reading books on autism or autobiographies by autistic people, I realized how much of it applied to me.

It took a bit longer (and a few tests) to get a confirmation from experts, and when it came, many people still had doubts. The question that came up the most often was, “But how was this never detected before?” Autism is generally noticed at a much younger age, and it seemed that for most of my life, I had managed to disguise myself as “neurotypical”, meaning someone whose brain works similarly to most people.

The current prevailing hypothesis to explain this, based on an IQ test taken as part of the evaluation process, is that I am privileged to have higher-than-average intellectual capacities, which has allowed me to partly compensate for the different wiring of my brain. One way to illustrate this is to use a computer analogy: in a way, my CPU runs at a higher frequency, which has allowed me to emulate with software the hardware that I’m missing. What this also means is that it can be exhausting to run this software all the time, so sometimes I need to be by myself.

As you can imagine, realizing at 31 that you are on the autism spectrum changes your perception dramatically; everything suddenly starts to make sense. I’ve learned a lot over the past two years, and this increased metacognition has allowed me to look at past events through a new lens.

In this essay, I want to share with you some of what I’ve learned, and share my current understanding of how my brain works, notably through my experience as a Wikimedian.

One caveat I want to start with is that autism is a spectrum. There’s a popular saying among online autistic communities that says: “You’ve met an autist, you’ve met one autist.” Just keep this in mind: What I’m presenting here is based on my personal experience, and isn’t going to apply equally to all autistic people.

The picture above was taken during Wikimania 2007 in Taipei. I was exploring the city with Cary Bass (User:Bastique) and a few other people. Looking back at this picture now, there are a few things I notice today:

- I’m wearing simple clothes, because I have absolutely no sense of fashion, and those are “safe” colors.

- I’m carrying two bags (a backpack and a photo bag), because I always want to be prepared for almost anything, so I carry a lot of stuff around.

- I’m sitting down to change a lens on my camera, because it’s a more stable position to avoid dropping and breaking expensive gear. I’ve learned that this habit of using very stable positions is actually a mitigating strategy that I developed over the years without realizing it, to compensate for problems with balance and motor coordination.

Spock

A good analogy to help understand what it’s like to be autistic in a neurotypical society is to look at Mr. Spock, in the Star Trek Original Series. The son of a Vulcan father and a human mother, Spock is technically half-human, but it is his Vulcan side that shows the most in its interactions with the crew of the Enterprise.

Spock and Kirk. “Leonard Nimoy William Shatner Star Trek 1968“, by NBC Television, in the public domain, from Wikimedia Commons.

Some of the funniest moments of the show are his arguments with the irascible Dr. McCoy, who calls him an “unfeeling automaton” and “the most cold-blooded man [he’s] ever known”. To which Spock responds: “Why, thank you, Doctor.“

As a Vulcan, Spock’s life is ruled by logic. Although he does feel emotions, they are deeply repressed. His speech pattern is very detached, almost clinical. Because of his logical and utilitarian perspective, Spock often appears dismissive, cold-hearted, or just plain rude to his fellow shipmates.

In many ways, Spock’s traits are similar to autism, and many autistic people identify with him. For example, in her book Thinking in Pictures, Temple Grandin, a renowned autistic scientist and author, recounts how she related to Spock from a young age:

Many people with autism are fans of the television show Star Trek. […] I strongly identified with the logical Mr. Spock, since I completely related to his way of thinking.

I vividly remember one old episode because it portrayed a conflict between logic and emotion in a manner I could understand. A monster was attempting to smash the shuttle craft with rocks. A crew member had been killed. Logical Mr. Spock wanted to take off and escape before the monster wrecked the craft. The other crew members refused to leave until they had retrieved the body of the dead crew member. […]

I agreed with Spock, but I learned that emotions will often overpower logical thinking, even if these decisions prove hazardous.

In this example, and in many others, Spock’s perception filter prevents him from understanding human decisions mainly driven by emotion. Those actions appear foolish or nonsensical, because Spock interprets them through his own lens of logic. He lacks the cultural background, social norms and unspoken assumptions unconsciously shared by humans.

The reverse is also true: whenever humans are puzzled or annoyed by Spock, it is because they expect him to behave like a human; they are often confronted with a harsher truth than they would like. Humans interpret Spock’s behavior through their own emotional perception filter. They often misunderstand his motives, assume malice and superimpose intents that change the meaning of his original words and actions.

Autism

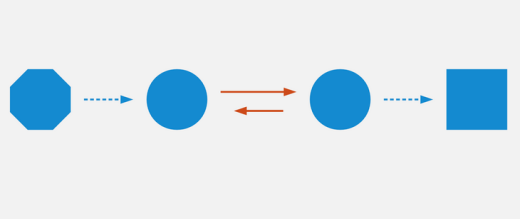

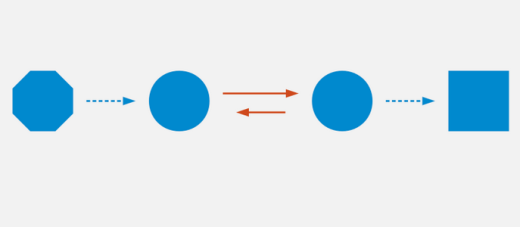

You’re probably familiar with the conceptual models of communication. In many of those models, communication is represented as the transmission of a message between a sender and a receiver.

In a basic communication model, the sender formulates the message, and transmits it to the receiver, who interprets it. The receiver also provides some feedback.

If you apply this model to an oral conversation, you quickly see all the opportunities for miscommunication: From what the sender means, to what they actually say, to what the receiver hears, to what they understand, information can change radically, especially when you consider nonverbal communication. It’s like a two-person variation of the telephone game. In the words of psychologist Tony Attwood:

Every day people make intuitive guesses regarding what someone may be thinking or feeling. Most of the time we are right but the system is not faultless. We are not perfect mind readers. Social interactions would be so much easier if typical people said exactly what they mean with no assumptions or ambiguity.

If this is the case for neurotypical people, meaning people with a “typical” brain, imagine how challenging it can be for autists like me. A great analogy is given in the movie The Imitation Game, inspired by the life of Alan Turing, who is portrayed in the film as being on the autism spectrum.

Still from The Imitation Game. © 2014 The Weinstein Company. All rights reserved.

Historical accuracy aside, one of my favorite moments in the movie is when a young Alan is talking to his friend Christopher about coded messages. Christopher explains cryptography as “messages that anyone can see, but no one knows what they mean, unless you have the key.”

A very puzzled Alan replies:

How is that different from talking? […] When people talk to each other, they never say what they mean, they say something else. And you’re expected to just know what they mean. Only I never do.

Autistic people are characterized by many different traits, but one of the most prevalent is social blindness: We have trouble reading the emotions of others. We lack the “Theory of mind” used by neurotypical people to attribute mental states (like beliefs and intents) to others. We often take things literally because we’re missing the subtext: it’s difficult for us to read between the lines.

Liane Holliday Willey, an autistic author and speaker, once summarized it this way:

You wouldn’t need a Theory of Mind if everyone spoke their mind.

How are you?

Many languages have a common phrase to ask someone how they’re doing, whether it’s the French Comment ça va ?, the English How are you? or the German Wie geht’s?

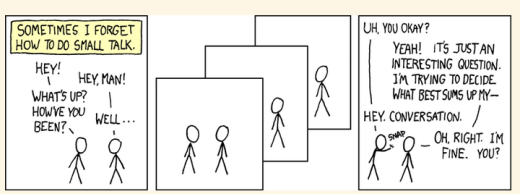

When I first moved to the US, every time someone asked me “How are you?”, I would pause to consider the question. Now, I’ve learned that it’s a greeting, not an actual question, and I’ve mostly automated the response to the expected “Great, how are you?”. It only takes a few milliseconds to switch to that path and short-circuit the question-answering process. But if people deviate from that usual greeting, then that mental shortcut doesn’t work any more.

A few weeks ago, someone in the Wikimedia Foundation office asked me “How is your world?”, and I froze for a few seconds. In order to answer that question, my brain was reviewing everything that was happening in “my world” (and “my world” is big!), before I realized that I just needed to say “Great! Thanks!”.

“Small talk” by Randall Munroe, under CC-BY-NC 2.5, from xkcd.com.

Privilege and pointed ears

This is only one of the challenges faced by autistic people, and I would now like to talk about neurotypical privilege. I’m a cis white male, and I was raised in a loving middle-class family in an industrialized country. By many standards, I’m very privileged. But, despite my superpowers, being autistic in a predominantly neurotypical society does bring its challenges.

The most common consequence I’ve noticed in my experience, and in accounts from other autistic people, is a feeling of profound isolation. The lack of theory of mind and the constant risk of miscommunication make it difficult to build relationships. It’s not anyone’s fault in particular; it’s due to a general lack of awareness.

Wikimania 2014 welcome reception. “Wikimania 2014 welcome reception 02“, by Chris McKenna, underCC-BY-SA 4.0 International, from Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine that you’re talking to me face-to-face. You don’t really know me, but I seem nice so you start making small talk. I’m not saying much, and you need to carry the discussion over those awkward silences. When I do speak, it’s in a very monotone manner, like I don’t really care. You try harder, and ask me questions, but I hesitate, I struggle to maintain eye contact, and I keep looking away, as if I’m making stuff up as I go.

Now this is what’s happening from my perspective: I’m talking to someone I don’t really know well, but you seem nice. I don’t know what to talk about, so I keep quiet at first. Silences aren’t a problem: I’m just happy to be in your company. I don’t have very strong feelings about what we’re talking about, so I’m speaking very calmly. You’re asking me questions, and of course it takes a while to think about the correct answer. All this “eye contact” thing that I learned in school is taking a lot of mental resources that would be better used to compute the answer to your question, so I sometimes need to look away to better focus.

This illustrates one of many situations in which each person’s perception filter caused a complete disconnect between how the situation was perceived on each side.

There are also many professional hurdles associated with being on the autism spectrum, and autists are more affected by unemployment than neurotypicals. I’m privileged in that I’ve been able to find an environment in which I’m able to work, but many autists aren’t so lucky. It’s been well documented that people in higher-up positions aren’t necessarily the best performers, but often people with the best social skills.

With that in mind, imagine what the career opportunities (or lack thereof) can be for someone who is a terrible liar, who has a lot of interest in doing great work, but less interest in taking credit for it, who doesn’t understand office politics, who not only makes social missteps and angers their colleagues, but doesn’t even know about it, someone who’s unable to make small talk around the office. Imagine that person, and what kind of a career they can have even if they’re very good at their job.

Casual relationships with colleagues and acquaintances are usually superficial; the stakes of the water cooler discussions are low, so people are more inclined to forgive missteps. However, friendship is another matter, and for most of my life, I have hardly had any friends, unless you use Facebook’s definition of the term. Awkwardness is generally tolerated, but rarely sought after. It’s not “cool”.

Most of those issues arise because you don’t have a way of knowing that the person in front of you is different. At least Spock had his pointed ears to signal that he wasn’t human. His acceptance by the crew of the Enterprise was in large part due to the relationships he was able to develop with his shipmates. Those relationships would arguably not have been possible if they had not known how he was different.

Computer-mediated communication

Let me go back to that conceptual model of face-to-face communication. Now imagine how this model changes if you’re communicating online, by email, on wiki, or on IRC. All those communication channels, that Wikimedians are all too familiar with, are based on text, and most of them are asynchronous. For many neurotypicals, these are frustrating modes of communication, because they’re losing most of their usual nonverbal signals like tone, facial expressions, and body language.

However, this model of computer-mediated communication is much closer to the communication model of autists like me. There is no nonverbal communication to decrypt; less interaction and social anxiety; and usually, no unfamiliar environment either. There are much fewer signals, and those that remain are just words; their meaning still varies, but it’s much more codified and reliable than nonverbal signals.

What there is online, instead, is plenty of time, time that we can use to collect our thoughts and formulate a carefully crafted answer. Whereas voice is synchronous and mostly irreversible, text can be edited, crafted, deleted, reworded, or rewritten until it’s exactly what we want it to be; then we can send it. This is true of asynchronous channels like email and wikis, but it also extends to semi-synchronous tools like instant messaging or IRC.

It’s not all rainbows and unicorns, though. For example, autists like me are still very much clueless about politics and reading between the lines. We tend to be radically honest, which doesn’t fly very well, whether online or offline. Autists are also more susceptible to trolling, and may not always realize that the way people act online isn’t the same as the way they act in the physical world. The Internet medium tends to desensitize people, and autists might emulate behavior that isn’t actually acceptable, regardless of the venue.

Autism in the Wikimedia community

Of course, one major example of wide-scale online communication is the Wikimedia movement. And at first glance, Wikimedia sites, and Wikipedia in particular, offer a platform where one can meticulously compile facts about their favorite obsession, or methodically fix the same grammatical error over and over, all of that with limited human interaction; if this sounds like a great place for autists (and a perfect honey trap) well, it is to some extent.

The “Wikipedians with autism” category on the English Wikipedia.

For example, my first edit ten years ago was to fix a spelling error. My second edit was to fix a conjugation error. My third edit was to fix both a spelling and a conjugation error. That’s how my journey as a Wikipedian started ten years ago.

Wikipedians are obsessed with citations, references, and verifiability; fact is king, and interpretation is taboo. As long as you stay in the main namespace, that is. As soon as you step out of article pages and venture into talk pages and community spaces like the “Village Pump”, those high standards don’t apply any more. There are plenty of unsourced, exaggerated and biased statements in Wikipedia discussions.

That’s in addition to the problems I mentioned earlier. As an autist, it can be hard to let go of arguments about things or people you care about. It’s often said that autistic people lack empathy, which basically makes us look like cold-hearted robots. However, there is a distinction between being able to read the feelings of other people, and feeling compassion for other people.

Neurotypical people have mirror neurons that make you feel what the person in front of you is feeling; autistic people have a lot fewer of those, which means they need to scrutinize your signals and try to understand what you’re feeling. But they’re still people with feelings.

If you’re interested in learning more about autism in the Wikimedia community, there’s a great essay on the English Wikipedia, which I highly recommend. One thing it does really well is avoiding the pathologization of autism, and instead insisting on neurodiversity, meaning autism as a difference, not a disease.

Conclusion

Steve Silberman, who wrote a book on the history of autism, presented it this way:

One way to understand neurodiversity is to think in terms of human operating systems: Just because a PC is not running Windows doesn’t mean that it’s broken.

By autistic standards, the normal human brain is easily distractible, obsessively social, and suffers from a deficit of attention to detail.

But still, neurodiversity has a cost. Sometimes, you’ll be offended; sometimes, you’ll be frustrated; and sometimes, you’ll think “Wow, I would never have thought of that in a million years”.

As I mentioned earlier, I believe Spock was only able to build those relationships over time because people were aware of his difference, and learned to understand and embrace it. Spock also learned a lot from humans along the way.

My goals here were to raise awareness of this difference that exists in our community, to encourage us to discuss our differences more openly, and to improve our understanding of each other.

There is a lot I didn’t get into in this essay, and I might expand on specific points later. In the meantime, I’m available if you’re interested in continuing this discussion, and you should feel free to reach out to me, whether in person or online.

Live long and prosper.

Read Next: How to beat anxiety without medication

Image credit: Shutterstock

An edited version of this post first appeared on Guillaume Paumier, CC-BY

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.