Len Kendall is the founder of CentUp. Prior to starting a company, he worked in PR where he helped put out fires and manage digital communications.

“Software may be eating the world,” but there’s still something extremely rewarding about making a physical product. Like most of the people reading this blog post, I’ve spent most of my career on digital endeavors, from websites to words and PowerPoint decks.

Alongside those digital properties, I was also into games. I began to notice the zombification of smartphone users who constantly walk around with their heads down, glued to a screen. This summer, I felt inspired to design my own smartphone game and decided to create and sell something that was tangible – a geocashing game called Cartegram.

Except there was a serious problem ahead of me: I don’t know how to code, and I’ve never built a physical product. Here’s what I learned along the way.

Exploring existing frameworks

As much as I’d like to, I wasn’t going to learn to program mobile apps any time soon. I also didn’t want to deal with the App Store and potentially not have my app approved after all that work and/or investment.

The only thing I really needed for this exploration game to work was a photo network with tagging functionality. Instagram is a perfect place to house Cartegram because it’s simple, accessible, and already has millions of users.

While games like Ingress or Geocaching require you to download their own app, Instagram is something that’s already on countless devices. And half (most of) the battle with getting people to play your mobile game is convincing them to download it.

Learning a new language

If you wanted to actually program your first mobile app, you might need to learn Java, Objective C or Swift. When you want to build a physical product, you’ll likely need to learn a vernacular you’re completely unfamiliar with as well.

It may not be as complex as programming, but it’s a critical step in getting the materials you need from the vendors who can provide them for you.

Before Cartegram I had no idea that stickers were referred to as “labels,” nor had I any grasp on words like “die-cutting” or “glue fold process.” Having a conversation with printers was painful at first because I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

Thankfully, many of the specialists I spoke with were helpful about guiding me through it, but my project is small and relatively simple. If you’re launching a large scale business selling goods, you need to know the lingo before you start investing time and money into potential vendor.

The minimum in “Minimum Viable Product” is still big

Scaling a digital product is relatively easy. You write a few lines of code and it works for one user or a thousand. But with physical products, it’s tough to build just a few quality prototypes.

Sure you can 3D print and scrap stuff together, but it will never look as polished as the final assembly line output will. That means if you want to get into physical products you need to start producing not 10 or 20 units, but hundreds.

The cost of creating the template for a tangible product is a set cost, so there’s simply no economical reason to not produce a significant amount from day one. To give you a specific example, it costs me only 20 percent more to print 1,000 Cartegram books versus 250.

When it comes to an MVP, apps can be tough. There’s not a great solution right now for building a prototype game that people actually want to play. If you want to release a decent game on the iPhone or even Android, you’re plunking down a minimum of $10,000 in time or money (and that’s being extremely conservative).

I ended up putting together a humble Kickstarter to make sure I could pay for the first run of printing Cartegram.

User feedback is scarce

With tools like Mouseflow, Google Analytics and Optimizely it’s relatively easy to get insight into how your digital product is being embraced by your potential and current customers. Not so much with a physical product.

Thoughtful design has to happen pre-launch because once a large batch of units have been created, you can’t tweak a line of text, or move an icon, or change the order of flow. It’s done, and it’s not going to be fixed until your next batch.

If you’re used to the idea of operating lean and tweaking digital products in real-time, know that’s not a path that will work with a physical product. Study past products and communities as much as possible, and think empathetically about how your customers are going to use your product.

The design thinking you apply before releasing your product might make or break you.

Icons, strong copy, and illustrations work really well in games whether they’re digital or physical. I decided to use such common game elements in a small portable package (a notebook) that essentially rests next to your phone when you’re exploring your city.

Not only does this format work well because of size, but the physical notebook complements the very tangible experience the players have while exploring the world around them.

Creating “stuff” responsibly

Personally, I hate the amount of “stuff” our society produces today. Things like fashion, packaged goods and food containers produce an insane level of waste.

So when I decide to create yet one more physical item for the world to potentially buy, use, and throw away, it was important for me to understand the impact – especially because this involved paper products.

The biggest takeaway is that there’s a misconception that eco-friendly products cost more than “normal” counterparts. Plant-based inks and compostable stickers for example are essentially the same cost as normal ones, yet the former is vastly friendlier to the environment across the production lifecycle.

As sustainable materials get more and more popular, it’s important that all new hardware entrepreneurs explore their options for reducing the footprint their product leaves behind.

Platforms on top of platforms

Building a native iPhone or Android app gives you a lot of control over the experience. Because Cartegram relies heavily on Instagram, one tweak to their interface or change in how tagging works could really create some big challenges for the community I’m building.

That said, any time you’re building a platform on top of a platform, this risk will exist.

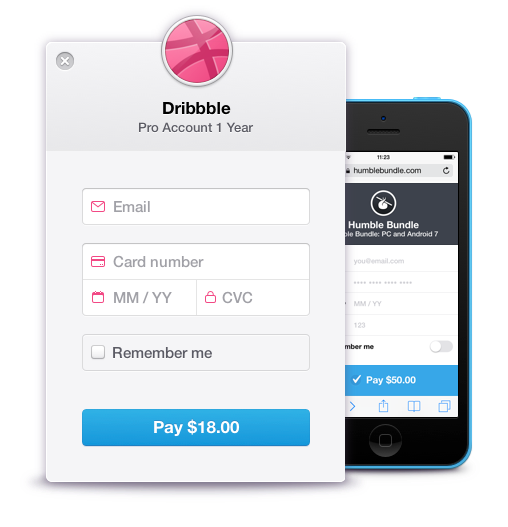

Even though the purchase process is going to be slightly more work for players than a screen tap, tools like Stripe make the process extremely easy. In other words, I’m sacrificing a bit of visibility for a hell of a lot more control over the experience.

Will it work?

Native apps do well because they’re customized to the exact specifications of a device. I’m creating a Frankenstein’s monster mobile app because it’s all I can do right now. I’m taking the non-technical hacking path to building a successful game and will continue developing it based on the needs of participating players.

Maybe someday Cartegram will push me to learn to build an actual mobile app, but for now, this game won’t have a single line of code written by me. But it will be environmentally conscious, with physical details and designs mostly under my control.

Read next: The ultimate guide to bootstrapping hardware startups

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.