These days it’s common for most Web firms to be focused on mobile. Facebook, Twitter, Google, you name it, they’re all building their smartphone (and feature phone offerings) in a bid to better position themselves and their user experience to take advantage of the growth of the mobile as a Web and entertainment device.

While Facebook and its ilk are focused on making themselves the center of the mobile messaging experience, or at least becoming the most used channel on devices, another genre of communications apps is gathering speed, and fast becoming a strong, alternative point of messaging from phones: mobile messaging apps.

The revolution is coming to mobile

While Skype led the charge to revolutionise long-distance calling on the PC, WhatsApp and a number of Asia-based messaging services have taken that principle to mobile with dedicated smartphone apps that connect people with free text messages and voice calls.

Building on the success of RIM’s BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) service (yes I just paired the words ‘RIM’ and ‘success’ together’) mobile messaging apps are cross-platform, but predominantly Android and iOS focused, and the field include services from Samsung, ChatON, and other handset makers.

And they’re popular too. Japan-headquartered Line has broken 45 million users in less than a year, Korea’s Kakao Talk is at 52 million worldwide (and a staggering 30 million, 90 percent of smartphone owners in its native market). Even Taiwan-based Cubie, a niche app that is barely three months old, has racked up 2 million downloads, demonstrating the size of the captive market.

WhatsApp is probably the best known service and, as of February, it was seeing 2 billion messages pass across its platform per day. For the sake of comparison, Kakao Talk is at 1.3 billion messages per day while Line’s figure is not disclosed.

Despite the initial feeling that free messaging might ‘kill’ operators’ SMS revenues, a good deal of carriers in Asia — and particularly Korea and Japan — have embraced apps as an opportunity to upsell smartphones and data tariffs to subscribers.

Operator relationships

While carriers have partnered with Facebook, Twitter and others, the coming together has been aimed at the opposite end of the scale, allowing low-end, pre-paid users to enjoy free access to Facebook’s free mobile platform — such as Facebook Zero — which is an entirely different angle to the premium appeal of messaging apps.

However, a number of those apps have introduced free calls services — such as Kakao Talk and Line — and seen operators back off and become more hostile, as is demonstrated by the throttling that Kakao Talk is suffering in Korea.

That caution is exactly why these apps can and will (and even do in some parts of the world) rival Facebook, as they offer a platform where users can easily text and (voice) talk to friends for free and, best of all, they are designed for mobile, so there’s no loss of features or issues with the performance of the apps.

While it may be naive to say that one particular communications medium will win out on mobile, an issue TechCrunch’s Josh Constine explores (even though there’s never been the case that one single medium has ‘won’ a platform), it is clear that mobile messaging apps should be written off at your peril.

More than just messaging

Not only are they gaining significant traction in Asia and other emerging markets that Facebook is looking to grow within, but they have relationships with operators and offer more functionality than social networks, albeit without the same context of Facebook and others.

Facebook’s mobile ‘messenger’ is essentially a stripped down version of the private messages side of its app. Compared to the dedicated mobile messaging apps, the Facebook offering feels heavy, taking longer to load and with more information than is often needed.

While many may value the fact that it shows older messages, they are not especially relevant to quick-fire instant messages and the app lacks the mobile-centric chat- like approach of WhatsApp and others.

There is a crossing of sorts in progress as, in contrast to Facebook, Japan’s Line is moving into app and content hosting (as below) with the impending launch of an API and platform for developers, as well as image sharing and profile pages. While it remains to be seen if its transition can be successful, the app has grown massively and is even turning in revenues – with the sale of its premium stickers netting $4.4 million in just two months.

Monetisation is a difficult issue, however, and while selling virtual goods has potential in Asia, a more robust approach to generating revenue may be necessary in the US and other Western markets.

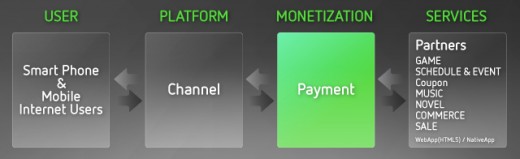

Other business model ideas include links to gaming sites, opt-in advertising, location-based services, e-commerce and premium content; such as images and videos from celebrities or brands. While it is interesting to note that WhatsApp is firmly against ads and monetises as a paid-for app after the first year – which helps it gain strong traction.

Certainly, with social networks increasingly focused on diversifying mobile revenues beyond advertising — which is a tricky approach to do well on mobile, given the limited space and more personal Web experience — these alternative approaches are interesting theories.

Facebook snapped up Instagram when it realised that it had become a focal point for social network users, and it is not outside the realms of possibility that the firm might consider a mobile messaging app acquisition, if it hasn’t already.

Kakao Talk (backed by China’s Tencent, among others) and Line (owned by Korea’s NHN) already have the backing off sizeable Web companies, but with a tonne of competitors cropping up, it remains to be seen how this growth and influence will affect the Menlo Park firm’s strategy, and its potential on mobile.

Update: I left out mentioning China’s 100 million plus user-strong Weixin as, though it is making moves overseas, China is a black spot for most Western social networks, and things in the country are on a different scale, as our recent QQ-Skype comparison showed. Nonetheless, Weixin (and its global ‘WeChat’ version) are further proof of the rise of mobile messaging apps.

In the US, Viber, Kik and others are also operating in the space, but I believe that Asia is where the real momentum is growing, thanks to a strong culture of instant messenger chat, which began with PC-based services like MSN.

I’ve also updated Kakao Talk’s user data, after the company told me it has 52 million users, rather than 40 million – which was the most recent figure we’d be provided with.

Feature image via Shutterstock / Tanewpix

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.