Microsoft recently taught its XiaoIce chatbot, a Chinese language conversational AI, how to interpret pictures as poems. We’re not sure if that counts as inspired writing, but it’s an interesting step toward better mimicking humans.

It’s not the first AI to write poetry, but it’s the first we’ve seen that can generate Chinese language poems inspired by images. There may be a little bit lost in translation, but some of the bot’s bars aren’t too shabby:

Wings hold rocks and water lightly

in the loneliness

Stroll the empty

The land becomes soft

The problem of teaching AI how to generate text descriptions or captions for images is a popular one among machine learning researchers. If an AI can eventually be taught to see the world the same way we do, starting with one image at a time, eventually we can teach it to see things our way all the time.

As humans, we can look at a picture and make inferences, point out objects, describe people’s facial features, and more – this is all based on our ability to draw upon context. Computer vision and deep learning artificial neural networks make it possible for machines to do this as well, but so far they’re nowhere near as good at it as an average human child.

One of the paths to creating a better autonomous image description AI is to keep tweaking a machine learning model until its output is indistinguishable from the work done by humans. But, at some point, simple descriptions like “I see a red apple on a brown table” are good enough to fool everyone. It’s pointless to try and figure out if a machine or a human wrote that, because it could obviously be either.

To further their work researchers have to find ways to make machines better at mimicking us, which means trying more difficult natural language processing tasks. And poetry is obviously more complex than simple captions.

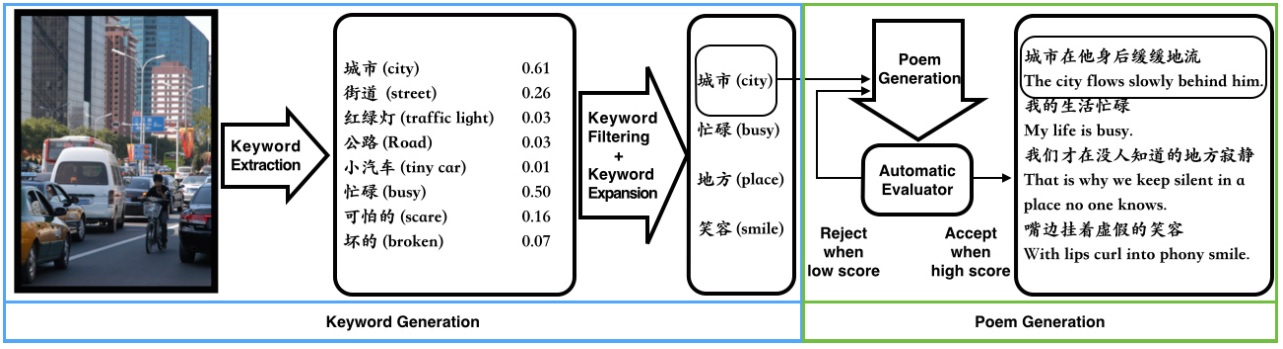

So how does it work? Scientists input some rules and then make a neural network split itself into a side that generates a poem, and a side that judges a poem. If the judge side thinks the rules have been met and particular poem is good enough for human eyes, it lets it through. A human then checks the results. If it’s not good enough, they go back to tweaking the parameters until its spitting out good stuff.

Microsoft has actually been working on this problem for awhile, having created an AI recently that generates English language poetry from images. But, writing Chinese poetry involves a different set of rules and parameters, even for humans. Chutian Xiao, a researcher studying English poetry at Durham University, says “it is a tricky thing to learn poetry and write poems in different languages.” and he’s just talking about humans.

When it comes to Chinese poetry, the rules have actually changed over the years. It’s harder, according to the Microsoft researchers working on the Chinese language bot, to write modern poetry:

While traditional Chinese poetry is constructed with strict rules and patterns (e.g., five-word quatrains are required to contain four sentences and each sentence has five Chinese characters, also words need rhymes in specific positions), modern Chinese poetry is unstructured in vernacular Chinese. Compared to traditional Chinese poetry, although the readability of vernacular Chinese makes modern Chinese poetry easier to strike a chord, errors in words or grammar can more easily be criticized by users. Good modern poetry also requires more imagination and creative uses of language. From these perspectives, it may be more difficult to generate a good modern poem than a classic poem.

So how good is Microsoft’s AI at writing poetry? Well, that’s entirely subjective. Futurism writer Dan Robitzki said its English language poet bot was as good as an angsty teenager. I, by contrast, rather liked some its stuff. But I’m more interested in LeCun than Longfellow, so I tend to lean in support of the machines.

To scientifically determine the efficacy of their poetry bot, the researchers conducted experiments where, according to them, people overwhelmingly chose the results from their bot over results from similar neural networks:

A large scale user study indicates that our generated modern poems earn much more favor than the generated captions. The reasons are that our generated poems are more imaginative, touching and impressive.

While a rose by any other name would surely smell as sweetly – to paraphrase The Bard – whether or not a machine can actually create art, much less poetry, is still up for debate.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.