Microsoft Research and UN scientists have teamed up to build the first general-purpose computer model of whole ecosystems across the entire world. The project was detailed in a recent Nature article titled “Ecosystems: Time to model all life on Earth,” which unfortunately requires a subscription. Thankfully, details have started to leak out to more public sources of information.

The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), a collaboration between the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organization, and WCMC, a UK-based charity. Scientists from the group specialize in biodiversity assessment, and according to the site, the authors of the Nature paper believe the type of model they are developing “could radically improve our understanding of the biosphere and inform policy decisions about biodiversity and conservation.”

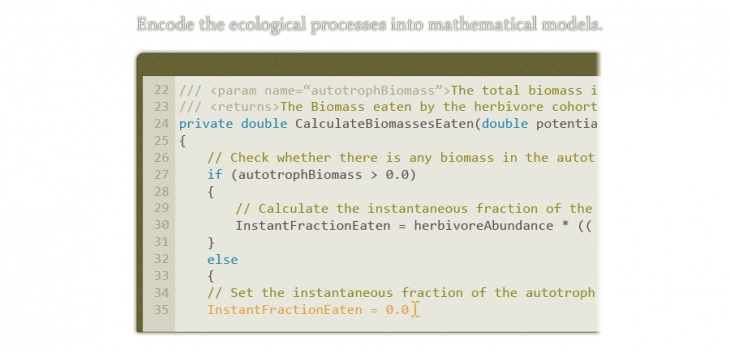

The vision is to build General Ecosystem Models (GEMs), the ecological equivalent of General Circulation models (GCMs), which are used in climate change science to simulate the physics and chemistry of the Earth’s atmosphere. The point of GEMs is to capture the complete structure of an ecosystem in the world by simulating processes such as feeding, reproduction, migration, and death, in order to help design future conservation policy.

By mapping the flows of energy and nutrients within the food chain over time, organisms could be grouped not by species but by their key functional characteristics: plants, birds, mammals, warm blooded, nocturnal and so on. From there, ecologists could assess a given ecosystem’s health, model what happens to the various groups over time as well as how it might change to a natural or human disturbance.

Over the past two years, the two groups have built a prototype GEM, the Madingley Model, for terrestrial and marine ecosystems that uses real data on carbon flows as a starting point. It’s nowhere near as comprehensive as a full GEM is supposed to be, but it’s the most ambitious attempt yet. The ultimate goal, according to the team, is not to develop a perfect model – but rather to trigger the creation of a set of competing models as other ecologists become encouraged to suggest improvements, adaptations, or complete replacements.

Image credit: Roberto Ribeiro

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.