Back in 2015, when the the world was just beginning to pay serious attention to virtual reality, Microsoft surprised everyone by announcing HoloLens. Instead of surrounding you with virtual imagery – like Oculus and every other VR company – HoloLens brought the digital world into the real. To date, it remains one of the coolest things Microsoft has ever made.

But along with HoloLens came Mixed Reality, a term that seemed to confuse pretty much everyone not working in Redmond. ‘Virtual’ and ‘augmented’ reality were the established lingo, and HoloLens seemed to be just a fancy form of the latter. ‘Mixed’ reality reeked of marketing buzzword, it sounded lame, and so I avoided it as much as possible.

Now I’m starting to budge. In the last two years – culminating in this week’s Build conference – Microsoft has laid out a foundation for its grand scheme to fundamentally change how we interact with our devices. Knowing why Microsoft so stubbornly adheres to mixed reality is crucial to understanding how it plans to get there.

HoloLens was just the start.

Mixed Reality includes AR, VR, and beyond

Over the past few months, I’ve had several discussions about mixed reality with Greg Sullivan, Director of Communications for Windows and Devices at Microsoft. In each, he’s repeatedly drilled into my head the idea that mixed reality is a spectrum – one that encompasses VR, AR, and everything in-between. In fact, the term has academic origins that long predates modern virtual experiences.

So no, you’re not wrong to call HoloLens an AR headset, it’s just that AR is but one part of the mixed reality spectrum. The term also encompasses a wealth of other device categories:

- Fully immersive VR headsets like Rift, Vive, and Microsoft’s offerings coming later this year.

- Camera-based AR, like Snapchat’s funky masks or games like Pokemon Go.

- Augmented virtuality experiences, whereby real-world elements are brought into a virtual experience.

- Potential future devices, that can do the best of both worlds, changing between being opaque like Rift, or transparent like HoloLens.

While HoloLens happens to be an AR device, Microsoft would be doing itself a disservice to limit its scope to that bit of spectrum. HoloLens was the first device in the Windows Mixed Reality platform, which seeks to enable immersive experiences in all the above form factors.

But why go with HoloLens first? After all, VR headsets seemed to have more immediate consumer applications for things like gaming, and are a lot less expensive to produce than HoloLens.

According to Sullivan, Microsoft wanted to start by solving the more difficult problem. VR headsets have the luxury of obscuring the real world. You can create more interesting experiences with some environmental interaction, but VR can be fun even while your feet are stationary.

HoloLens, on the other hand, required an understanding of the environment around the user. It was a deeper problem to solve, but one that would reap rewards; Sullivan says Microsoft used what it learned from HoloLens to create affordable VR headsets that beat the competition to the punch with inside-out tracking.

That means that, unlike Oculus and Vive, Microsoft’s partner VR headsets can map your movements in the real world without the need for messy external sensors. I’ve spent a fair amount with the Acer dev kit, and it works incredibly well.

Add the fact that they also require lower minimum specs, and are much cheaper than similarly spec’d competition, and it’s clear Microsoft was onto something. Here’s hoping those fancy new controllers work just as well.

Mixed reality is about shared experiences

There’s a second meaning to the ‘mixed’ part – Microsoft wants different device categories to not only coexist, but to seamlessly interact with one another.

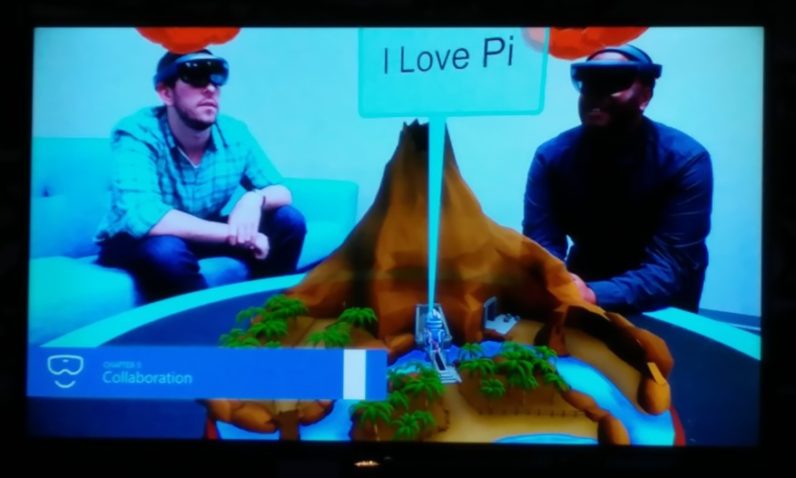

At Build 2017, I was able to participate in a multiplayer, mixed reality minigame where some players used HoloLens, and others used Acer’s VR headset. The combination of AR and VR was a pretty trippy experience.

Players with the VR headset inhabited a small virtual island, while players with HoloLens saw a birds-eye view of the action. The two had to work together to solve basic puzzles and navigate through the island.

I played the game from both perspectives, and rudimentary as it may have been, it was an enticing taste of the shared experiences to come. When I was using the VR headset, I was a tiny man on the island, and could look up to see my HoloLens-wearing overlord. While wearing HoloLens, I could shoot lightning bolts at the tiny people in the VR island – all by being aware the other players were right there in the same room with me. In the future, you might even be able to join in on such a game with a smartphone-based AR app.

It was here that it all really clicked. Here you have what seemed to be two completely different device categories seamlessly interacting with each other thanks to the shared Windows Mixed Reality platform. These devices are not so separate as they seem, and having them work together is critical as more mixed reality headsets arrive in the coming years.

Compare that to the walled garden of pretty much every other immersive platform right now. Vive, Oculus, and Sony only allow you to interact with specific VR headsets. Moreover, these companies have a financial incentive to keep things that way.

It’s the opposite with Microsoft. Microsoft is making Mixed Reality a core part of Windows, and Windows succeeds because of diversified hardware. We already know the company is partnering with six manufacturers so far for its VR headsets, and you can bet there will be third-party HoloLens devices once production costs come down.

Who needs monitors when you have holograms?

Microsoft needs to start developing those hardware partnerships now, because in the future, mixed reality wearables might be our primary way of interacting with Windows.

Think about it: once mixed reality headsets are both powerful and practical enough, we won’t need monitors. High-tech Glasses or contact lenses could contain virtual displays that we can resize and arrange to our choosing – Zuckerberg certainly thinks so. Holographic keyboards and trackpads might even someday become a thing.

When that time comes, we will have the portability of a smartphone with the versatility of a desktop. But laptops, desktops, and smartphones aren’t going away anytime soon, and VR and AR will remain roughly separate experiences at first. During that slow transition, we will need a way for all these different devices to live together and interact with one another.

That’s where Microsoft is trying to get a head start, by establishing mixed reality as an integral part of the Windows infrastructure and getting partners to sign up for the ride. The company essentially wants to do with mixed reality what Windows 95 did for the personal computer: make it accessible and affordable.

If that all sounds like far-fetched futurism, know that there’s some precedent – Sullivan tells me there’s at least one engineer at Microsoft who’s renounced physical monitors for a holographic multi-display array. It’s just a matter of time until that becomes a practical reality for everyone.

The long read ahead

All this isn’t to say mixed reality doesn’t still have its problems. Perhaps chief among them, Microsoft will need to make clear where products lie on the mixed reality spectrum.

That’s not a big issue right now. HoloLens is not yet a consumer product; it’s current iteration is built for devs and the enterprise, and it costs $3,000. But what happens if five years from now there are a myriad of AR-type and VR-type headsets being sold side-by-side in stores, all labeled ‘Mixed Reality’ devices?

Of course, anyone who follows a tech blog could tell AR and VR headsets apart at a glance, but the average consumer, not so much. At that point, Microsoft will have to either start using terms like AR and VR to differentiate the headsets, or come up with new buzzwords altogether.

Still, at least I now understand why Microsoft is so adamant on calling everything Mixed Reality. Since HoloLens was first announced, the company has put in more work to prepare for an expanded immersive ecosystem than pretty much anyone else. It wants everyone to know that.

Follow all our coverage of Microsoft’s Build conference here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.