Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse dream is giving investors nightmares. His $10 billion annual bet on an “embodied internet” preceded a plunge in Meta’s value, a first-ever quarterly revenue decline, and grim forecasts for growth. Horizon Worlds, his initial foray in the space, has only added to concerns. The social platform is regularly derided for slow uptake, persistent bugs, and risible avatars.

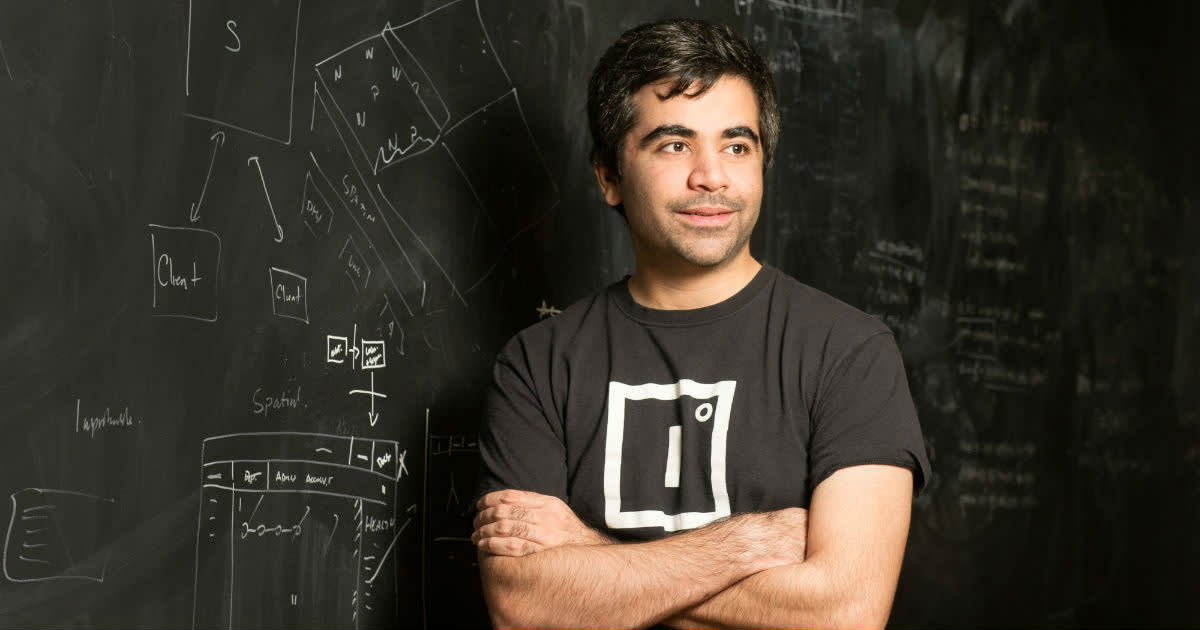

Despite the mounting criticisms, Zuckerberg remains bullish about making Facebook a “metaverse company.” But for Herman Narula, the CEO of UK unicorn Improbable, Meta’s vision overlooks a fundamental issue.

“The problem is VR,” Narula said last week at Stanford University. “The bet on the hardware is just so costly, so tangential to the main value proposition of the metaverse, and [it’s] so difficult to see how they claim that investment back.”

Narula has his own metaverse plans. His company has spent a decade building immersive virtual worlds, from wargaming simulations for the US Army to an interactive party for 1,450 K-pop fans. He’s also written a book, Virtual Society, which outlines a theoretical framework for the metaverse. In Narula’s mind, this comprises a network of digital experiences that people can traverse — without donning a headset. Instead, they can be entered with just a phone or PC.

Narula admits that VR offers impressive immersion. But he says the metaverse needs something more important: presence.

He describes immersion as “the feeling that the world is real.” Presence, in contrast, is “the feeling that the world thinks you are real.” To create this sensation, user actions must produce reactions and ripples throughout the virtual world.

Narula asserts that presence doesn’t need VR. As evidence, he points to the “proto-metaverses” Minecraft, Roblox, and Fortnite. Despite fairly rudimentary graphics, the games evoke a presence that’s put them among the most popular in the world.

According to Narula, Zuckerberg’s VR-based metaverse has several issues. One of them is cost: the new Quest Pro VR headset retails for a whopping $1,500. Technical improvements — including eye tracking and mixed reality capabilities — provide major upgrades, but the price tag puts them out of reach for most customers.

Zuckerberg has acknowledged this barrier. He describes the new headset as a “prosumer” device, and plans to launch a consumer-grade version next year. Research suggests the public won’t be flocking out to buy one.

Meta has also taken tentative steps to integrate mainstream devices. The company plans to launch both web and mobile versions of Horizon Worlds, which would enable access without a VR headset. Yet this risks creating a two-tiered experience.

Revving virtual engines

Naturally, Narula has his own plans for producing presence. He pitches Improbable as a peerless platform for a crucial component of the metaverse: capacity. To back up this claim, Narula points to a metric called communications operations (ops) per second.

“It’s the horsepower of the metaverse.

The number of ops per second reflects how many different things can simultaneously occur in the metaverse. Improbable’s cofounder, Rob Whitehead, describes it as “the ‘horsepower’ of a virtual world.”

Whitehead describes the rough formula for ops per second as follows: # of players in a space x player density x update rate. To demonstrate how it works, he refers to the arena shooter Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. If the game has 10 players who can all see each other, and the server sends player updates 64 times per second, the calculation would be 10 x 10 x 64 = 6,400 ops per second.

As the players, density, and fidelity are all scaled up, this number can rise dramatically. For instance, a battle between 8,000 players of EVE Online that sends player updates just 0.1 times per second would produce 6.4 million ops per second.

Improbable, meanwhile, claims it can now process 2 billion ops per second.

Operations per second is a critical metric to compare virtual worlds – you'll hear @HermanNarula , @MSquared_io and myself use it often. You can think of it like the "horsepower" of a virtual world – the raw connective capability it has. pic.twitter.com/nGLXWfKziH

— Rob Whitehead (@RJFWhite) September 10, 2022

To explain the computational complexity of virtual worlds, Whitehead evokes a dilemma called the “Metaverse Sniper Problem.”

“When you zoom in through the scope of a sniper rifle, you need to be able to see an area of the world far away in high-fidelity to be able to get an accurate shot,” he said.

“This is difficult in traditional games with 60-100 players as the networking requirements of the architecture scale quadratically: a 200-player game has 4x the networking requirements of a 100-player game. Therefore to power metaverse experiences with [tens of thousands] of players, you need a fundamental step change of technology.”

Interconnecting worlds

The dominance of VR isn’t Narula’s only issue with Meta. Like many critics, he’s concerned about the company — or, indeed, any single company — controlling the metaverse. To avoid this ghastly future, Narula wants to integrate another contentious technology: blockchain.

Backers of a blockchain-based metaverse point to two key benefits: decentralization and interoperability. The former derives from storing data on a distributed ledger, which isn’t controlled by any one company. Interoperability, meanwhile, is achieved by cryptographically securing data exchanges. Your avatar’s clothes, for example, could be safely ported between different virtual worlds.

“That’s what makes it more than a game.

Blockchain isn’t the only means to provide this portability. Alternatively, companies could agree on rules and systems for facilitating digital transfers across various platforms. Web3 advocates, however, warn this would tighten Big Tech’s stranglehold on our data.

Yet this is only one argument that they have to win. Blockchain boosters also have to address concerns about the tech’s scalability, environmental impact, and propensity for crypto cash grabs. Nonetheless, Narula appears confident that the benefits will outweigh the negatives.

The 34-year-old envisions blockchain enabling transfers between worlds. Companies would build metaverse businesses by sharing customers, while users would enjoy meaningful experiences across platforms. According to Narula, VR and AR are merely tangential to all these interactions.

“They can totally play into building more engaging experiences, but they’re not the disruption,” he said. “The disruption is that the events — the things that happen in these worlds — can suddenly start to matter a lot more. That’s what’s creating a different relationship between us and these experiences. That’s what makes it more than a game.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.