“My name is Simon Wheatcroft, I’m an ultramarathon runner, father, and Glass Explorer,” explained the 30-something man on stage at Wired’s annual London conference.

Anyone who’s ever taken on the momentous challenge of running a marathon will know that the 26.2 miles of exertion on race-day is only a small part of the achievement. The months of (blood), sweat and tears that go into training for the occasion is where the real hard work lies.

Now, imagine the final distance you’re training for isn’t 26.2 miles. Imagine it’s 100 miles or more. And imagine having to pound the pavements on your own, without the benefit of vision. Only then can you appreciate what Wheatcroft has achieved in the past few years.

Wheatcroft was diagnosed with a degenerative eye disease at 13 that led to him becoming legally blind by the time he was 17. Around 10 years later, he took up running, a hobby that has blossomed with a little help from mobile technology.

Here’s his story.

Running man

“I started running because I was broke, and needed something to do,” explained Wheatcroft, somewhat matter-of-factly. “I figured running could be cheap, so I went out with an old pair of shoes I owned, and started running.”

Behind his house lay a football (soccer) pitch, and he would position himself between the goalposts and run up and down the field. “Around the same time, I was using an app on my phone called Runkeeper, which gave audio feedback, so for the first time ever I could know things like distance and pace,” he explained. “I managed to run one mile, but there was a problem – it was starting to get a little bit dangerous because of dog-walkers. They assumed I could see, I assumed they would move. It was time to find somewhere new to run.”

Wheatcroft’s wife then drove him to a closed road near his home to run. “So my wife dropped me off, and there was double-yellow lines – that was quite easy as I could feel them under foot and make sure I was running along the lines.”

This basically helped him keep on the straight – if he started to drift, he could ‘feel’ his way back on to the edge of the road. “I was doing this in Runkeeper, and it was around this time that whenever I ran over some (steel) grates, Runkeeper would say I’d run 0.3 miles. So I thought maybe I could pair what it feels like underfoot, with the distance markers from Runkeeper, and learn to run.”

This is exactly what Wheatcroft did. Over the past four years or so, Wheatcroft has run solo by learning the environment around him, aided by audio cues from Runkeeper on his phone, and in more recent times, through strapping Google Glass to his face.

One day, his wife dropped him off, and he ran up and down the closed road as usual, but took things a step further by moving out onto the dual carriageway, guided in part by the yellow lines along the side. “I got to the bottom, and I burst into tears – I couldn’t believe I’d achieved this. I was running on the open road, it was no longer the football pitch, it wasn’t a closed road – this was a real road with traffic,” he said. “I knew one thing though – I needed to get back to the closed road before my wife found out.”

So for the next while, slightly deceptively, he began to learn to run the open road. He learnt what it felt like underfoot, and paired that with the distance on Runkeeper.

Grass, bushes and other environmental objects were used by Wheatcroft to help him navigate, but obviously things like road signs and lampposts were problems – “you have to learn where they are by running into them. You don’t make that mistake a second time,” he adds.

Things progressed, and after telling his wife what he’d been doing, she eventually got on board with the idea and Wheatcroft started to reach distances of 10 miles. He then entered a 100 mile race, one of a number of distances that fall under the ‘ultramarathon’ banner, for which he had six months to train.

He decided that a team of guides on bikes would be of use for the route, but all his friends who had agreed to help out became injured six weeks from the race start. “I went on Twitter and asked if anyone was willing to help,” he said. “I put out one tweet, and within three days I had 20 strangers willing to help me run 100 miles.”

Six weeks later, he turned out for the race in the hilly Cotswolds. He got to 50 miles and broke down, but didn’t quit. He pushed himself on to 83 miles until he could no longer stand, and was pulled from the race.

Boston to New York

While he has run all sorts of official races, from 5km to half-marathons and beyond, he has never run an actual organized 26.2 mile marathon. “There was only one marathon I ever wanted to run – and that was New York,” he explained.

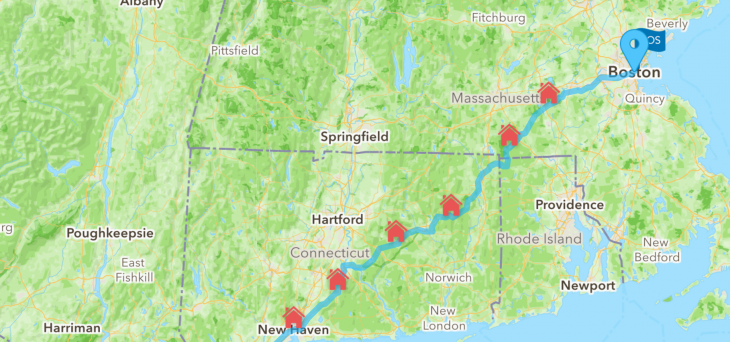

In a couple of weeks time, Wheatcroft will compete in the New York Marathon. But before that, he’ll run from Boston to New York – 206 miles – documenting every step of his journey with Google Glass.

“Boston is the home of Runkeeper, which is what made this possible – if it wasn’t for them, I’d never have started to run,” he explained.

To make things even more interesting, Wheatcroft isn’t even taking a guide. He’s going to navigate from Boston to New York with just his phone and social media, and Airbnb hosts helping out along the way for accommodation. “The idea is this – on the Saturday I fly to the US, I’ll use Twitter to get from Boston to New York, and everyone can follow along online.”

He’ll use Google Glass to stream and document the endeavor, and there will be live GPS tracking.

‘Glass’ ceilings

The use of Google Glass is interesting on many levels. Yes, it opens things up to broadcasting to the world, but on a practical level it gives Wheatcroft easy access to his phone’s functionality, which means he can keep both his hands free.

“Glass can see. And I can’t,” he says. “I thought, ‘maybe this technology can fill in the gaps’. Now I can just ask Glass directions to where I want to go, and receive audio feedback. It’s not a replacement for my eyes, but it’s something that can assist.”

This is what’s possible now, and when he runs more than 230 miles in early November. “What really interest’s me is what’s possible next year, or what’s possible the year after,” says Wheatcroft. “Hopefully, new technology will arrive and I will be able to use Glass in unique ways. And do even greater things.”

Google Glass is still an early-stage product in many respects, with limited global availability and a price-point that would preclude many from buying one. But it’s clear that it’s more than a novelty wearable for those with cash to splash. It’s a useful tool for the visually impaired, as Wheatcroft has previously explained:

“….using a phone with a guide dog or cane is impossible. Gestures often require two hands, so I need to drop the dogs harness, stand still and begin the process of multiple taps and gestures to find the app and input the location. With Glass however, I have hands-free operation, I can control Glass while continuing my walk down the street.”

Even beyond navigating, Wheatcroft envisages a future where “Glass can read a menu to me in a restaurant […] or perhaps opening a book and have it read aloud, reading a book – that is something I have not been able to do in a long time.”

While Wheatcroft may not be able to see the screen, Glass can provide vital audio cues that serve many purposes.

The one thing that’s on Wheatcroft’s radar for the next 12-18 months, is to compete solo – having only trained solo previously. “I feel there is a place on Earth where a blind man can run alone – and that place is the desert,” he says. “So the idea is to run across the Sahara in a race, to see if I can beat them (other runners) using technology.”

All he needs is the GPS coordinates, to keep on running, and beat everyone else. Sounds easy, right? “I often see technology as an opportunity, a new piece of technology always opens up a new possibility,” he says.

Meanwhile, be sure to track Wheatcroft’s progress from Boston to New York here.

Related read: Meet Joseph Tame: Marathon runner, art runner, iRunner

Thumbnail image credit – Runkeeper

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.