Mark Zuckerberg’s 18th pick for his Year of Books is Daron Acemoglu and James Robinsons’ Why Nations Fail. Take a spin through to learn why some nations are economic powerhouses, why others tank, and how the authors’ new theory can divine the future of the US, China and the world.

Riddle me this: Why has Botswana, a landlocked country in the south of Africa, become one of the fastest-growing countries in the world, while other African nations — Zimbabwe, the Congo and Sierra Leone among them — remain caught in a miasma of violence and poverty? You might chalk it up to weather, like our friend Ibn Khaldun; you might call it the fault of culture, or maybe attribute it to simple ignorance of good policy.

And you’d be wrong on every count.

Pick number 18 in Mark Zuckerberg’s book club offers new factors in what defines success for a nation. Drawing upon fifteen years of original research, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson conjure examples from the Roman Empire, Mayan city-states, medieval Venice, the Soviet Union, Latin America, England, Europe, Africa, and the US, as they develop a new theory of why some nations founder where others thrive. The book illuminates what we can predict about China, how to move millions out of poverty, and whether the US’s glory days are over. Read on for its core principles.

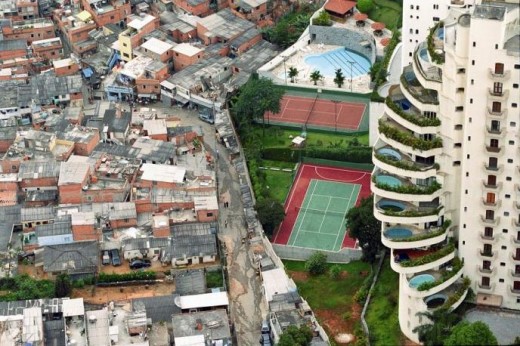

Why Nations Fail explores why even today some nations are trapped in what seems to be an immitigable vortex of poverty while others prosper — or at least appear on the way to prosperity. Acemoglu and Robinson believe that political and economic institutions are the keys to long-term prosperity and expose precisely how they can be the keys to breaking or perpetuating a nation’s cycle.

Who wrote it?

Daron Acemoglu is a professor of economics at MIT and ranks among the most highly respected economists in the world. He received the John Bates Clark Medal, which is regarded as the precursor to the Nobel Prize.

James A. Robinson is a political scientist, an economist and a professor at Harvard. He has done research in Latin America and Africa, and is widely considered an expert in foreign aid.

3 Things You Should Know from Why Nations Fail

1. “Integrative institutions” are what undergird nations with lasting economic success.

Nearly all nations that have achieved a high standard of living have what’s known as integrative institutions.

Integrative institutions — political and economic institutions that involve the entire society—are what enable wide democratic participation in politics and the economy. They’re characterized by a panoply of individual rights, such as the freedom to choose a profession and access to education. They set incentives for education, performance, and innovation, and create a wider income distribution, preventing small elite groups from abusing their power and any potential profit from unfair competition.

2. “Extractive institutions” — authoritarian regimes, for example — are the prevailing force in poorer countries.

Historically speaking, integrative institutions are an exception to the rule. Exploitative, so-called “extractive” institutions are unfortunately the norm.

This type of institution is designed to benefit only a small elite whose priority is to retain control over politics and the economy. Despite this common fundamental trait, the individual character of extractive institutions varies from country to country. In North Korea, for instance, citizens are not granted the right to own property. In the Congo, institutions are still set up the way they were in the days of colonialism: a small elite cashes in on the country’s resources, and raw materials are sent out of the country as quickly and cheaply as possible.

3. Political change always means institutional change, which takes time.

If it’s possible at all, institution swapping takes time. The authors explain that initiating political change is usually challenging and its consequences tend to be unpredictable, since many countries are stuck in a vicious cycle that is extremely challenging to break.

To cite a recent example, Hosni Mubarak’s downfall may have been a step towards democracy in Egypt but it also created the risk that a military regime operating the same sort of authoritarian institutions would fill the power vacuum. That’s because many people are afraid of instability, a state of affairs that would be characteristic of a true democracy in its beginnings.

And fear and uncertainty? It’s natural in these situations because it moves slowly and feels tenuous. Functioning democracy can’t happen overnight. Take France, for example: after the French Revolution ended in 1799, it took 80 years for a stable democracy to form! It’s unrealistic to assume that this sort of development could take place in just a few years in countries like Egypt, but the possibility isn’t off the table.

One interesting concept from Why Nations Fail:

Foreign aid should be targeted at institutional reforms, not at supporting authoritarian systems. Here’s a case in point: in Afghanistan, billions of dollars in foreign aid were squandered because they were being poured into the wrong projects. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Afghanistan had the opportunity to establish a democracy. But not much of the money it received from foreign aid was used for rebuilding — a large portion of it trickled away into administrative affairs.

One surprising idea from Why Nations Fail:

Authoritarian systems fail because they do not create the right kind of incentives. But the free market will. In a free market, incentive systems make an uptick in innovation and efficiency possible. In authoritarian systems, however, sustainable technological change and increased productivity aren’t usually at the forefront. In these systems, incentives for innovation and efficiency boosts are usually determined centrally, which rarely leads to satisfactory results.

Authoritarian institutions also frequently fall prey to the complexity of their own plans.

Under Stalin’s rule, for instance, Soviet laborers often received a good third of their wages as a bonus when certain production quotas were reached. However, this prevented innovation. Why? Because innovation causes short-term productivity loss — albeit loss that ends up creating long-term productivity increases. As a result of the regime’s bonus rule, laborers merely focused on working for their bonus money rather than working on new innovations.

If you remember only one thing, make it this:

Rich and poor countries differ, above all, in their political and economic institutions. In wealthy countries there are integrative institutions (i.e., democratic institutions that involve the whole society), whereas in poor countries there are extractive institutions (i.e., authoritarian and exploitative institutions that reinforce the power of an elite class).

Read the rest of Why Nations Fail in its entirety, or, read the book’s highlights in a 10-minute summary over on Blinkist — free!

➤ This post originally appeared on Page19

Read next: What TNW is reading

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.