Anthony Rose is co-founder and CTO of Beamly, the social and content network for television. Before Beamly, he headed up BBC iPlayer from 2007 to 2010.

The UK Government’s creation of a set of local television stations can now be considered a failure.

The source of the failure is a lack of understanding of how people find and consume local media in the age of global websites and online personalization. Even the forced insertion of local TV channels at the top of the TV guide to attract drive-by traffic from users browsing the guide could not generate viewers. The rigid rules that govern local television prevent the adoption of alternate approaches, leaving local television in a no-win position under the current license terms.

Way back at school you may remember studying Walter Christaller’s theory of the Hierarchical Patterns of Urbanization, which explains how small shops flourish in local villages despite their small range and higher prices, while larger supermarkets with greater product range make their appearance in larger towns. For someone living in a small town, the convenience of a short trip to the local store justifies the higher pricing and limited range – that is why small local shops can exist.

But on the internet – or indeed on TV – that model is inverted. It’s actually easier to go to a global website such as Google, BBC, Yahoo, YouTube, etc, to find a combination of local and global news, weather and entertainment than it is to ‘drive’ to a local website that delivers, inevitably with poorer production values and a lower budget, just a local slice of that content.

Personalization and the old media mentality

In the future, the rise of personalization technology means that you’ll go to one of a small number of global sites, which will deliver a tailored set of news and entertainment just for you, often combining global news with local stories. This will happen seamlessly and automatically based on knowledge of your location from your IP address, social network profile, mobile phone number, and more.

I first realized this some years ago when I met with local radio teams to discuss incorporating local radio content into BBC iPlayer – i.e., iPlayer would be a global destination that would create a “channel me” that included Doctor Who and your local news, in one unified interface.

I was struck by how the local radio teams opposed this idea, wanting to maintain the presence of their local channel, while simultaneously lamenting the decline in user numbers to local stations.

The internet thus inverts the physical laws of locality – it takes more effort to find a local station or web site than it takes to get a mix of global and local content delivered to you in the big global sites.

Unfortunately this realisation seems to have been lost on the Government, which decided to recreate the TV equivalent of those small local shops that have no future in a world of global online properties.

‘Hijacking’ the program guide

The Government then sought to create an uneven playing field to drive traffic to those local stations by placing them at the top of the Electronic Program Guide. For those who don’t know the term, an Electronic Program Guide (or EPG as it’s known to those in the trade) is the quaint late 20th century / early 21st century anachronism that is the on-screen channel list you scroll through to find a program to watch.

The Electronic Program Guide is arranged in numerical order – e.g.,

- Channel 1 is BBC 1 (unless it’s BBC 1 HD, which is Channel 101)

- Channel 2 is BBC 2 (unless it’s BBC 2 HD, which is Channel 102)

- ….

- Channel 18 is 4Music

etc.

Arranging television channels in numerical order makes about as much sense as arranging the telephone directory in numerical order – i.e. it works really well when you dialled 1 for Police, 2 for Fire, 3 for the Foreign Office. But after a few dozen entries the system begins to break down, and as we enter a world where cable and satellite TV viewers receive 500+ channels, it’s clear that the EPG’s days are short-lived, to be replaced by recommendation engines and personal ‘channel me’ guides that build a personal list of shows that are, or may be, of interest to you.

By the way, TV manufacturers know this well – all major TV producers are working on new models that downplay the numerical program guide in favour of new forms of program discovery based on showing you what’s popular, what’s trending, shows you’ve favourited, shows recommended for you based on your prior viewing.

In order to drive traffic to the local TV stations that it created, the Government sought to hijack the natural ordering of the TV guide (where the oldest and generally most viewed TV channels occupy the top slots, the ones with the lowest channel numbers) by forcing the insertion of local TV into Channel 8 in the Freeview guide, between ITV2 and ITV3.

The hope was thus that the millions of viewers flipping from ITV2 to ITV3 looking for something to watch would ‘drive by’ their local TV station and be lured to stay by the captivating local programming.

An analogy is a shopping mall placing the shoe resoling stand near the main entrance in the hope that some fraction of the thousands of people passing by on their way to Tesco would be compelled to want their shoes resoled. But times have changed, we don’t get shoes resoled any more.

It was a clever idea, and a brave experiment. But the numbers are in from the first few channels to launch – almost nobody watches local television – and on any measure the experiment must be declared a failure.

No room for experimentation

Now it should be said that the tech world is driven by innovation and experimentation, and in that sense the Government’s plan is to be applauded.

The crucial difference, however, is that in the tech world the outcome of an experiment is used to rapidly and iteratively lead to design changes. For example, Facebook, Google, Twitter and indeed my own company, Beamly, all do user-driven product development where we try something new, look at audience engagement, and then quickly iterate based on the results.

If you think of an Electronic Program Guide as being the TV equivalent of a Facebook feed – a big list of content that you scroll through – then any tech company would experiment with putting different content in the feed. At Beamly, we may try inserting a For You content recommendation into your feed, or perhaps even some local TV programming. We’d then measure the engagement rate and, well, if few people clicked on that content we’d ditch the idea and try something else.

The problem is that unlike tech companies that use experiments to drive innovation, experiments set up by legislation are doomed because there is no room for feedback, no ability to apply learnings, no ability to innovate. If the rule says that local TV stations must be at Channel 8 to trick people switching from ITV2 to ITV3 to stay and watch, but still they don’t, then the Freeview TV guide implementers, local stations and TV viewers are stuck with that.

But it gets worse.

Not only is the Government trying to legislate for a known current implementation, it’s trying to burden future innovation with an already failed proposition [PDF link]:

Licensed local TV services will gain appropriate prominence in electronic programme guide (EPG) listings enforceable through Ofcom‘s statutory code… The Government anticipates that all local TV services, whether they are licensed under this scheme or carried separately on internet protocol television or video on demand, will have the opportunity of discoverability on the front page of all EPGs.

So let’s see… will YouTube be forced to feature Estuary TV, devoted to covering life around the east coast town of Grimsby? Where? How? Will YouTube really be forced to feature ‘Discover Our Coastline‘, “An exploration of our local coastline and it’s (sic) fascinating story” on the YouTube front page?

That’s just it – in the new world of personalization there is no front page, the existing rules don’t apply, and the players are global sites, making news, content, social and entertainment available in fabulous new ways that the law cannot possibly anticipate.

I should be clear that there’s nothing wrong with local programming – we all want to know the local weather, find local movie listings, read about the changes to local bus routes, watch videos filmed in our suburb, and feel part of a local community. All good on that. But the way we’ll discover and engage with that content in the future won’t be by going to small isolated web sites or TV channels, it will be by finding and viewing that content within global sites and channels.

And there lies the opportunity for local programming: syndication. Instead of trying to model user behaviour based on reduced travel time to the local greengrocer, companies creating local programming should be looking to syndicate it into properties that users in that area are already visiting, where thanks to localization and personalization technology viewers or site visitors in that area will see it, share it with friends on social networks, etc.

An alternative is for local TV channels to take advantage of their privileged position in the TV guide to reinvent themselves, dot-com startup style, to offer programming that people might want to watch. Unfortunately, the same Government rules that granted them a free but commercially valuable and privileged position at the top of the TV guide also prevents them innovating in their content offering [PDF link]:

(5) Services shall be taken for the purposes of subsection (4) to meet the needs of an area or locality if, and only if—

(a) their provision brings social or economic benefits to the area or locality, or to different categories of persons living or working in that area or locality; or

(b) they cater for the tastes, interests and needs of some or all of the different descriptions of people living or working in the area or locality (including, in particular, tastes, interests and needs that are of special relevance in the light of the descriptions of people who do so live and work).

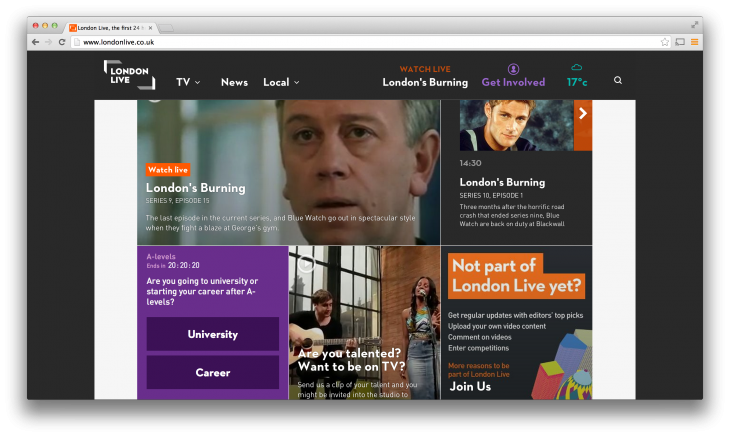

For London’s local TV channel, London Live, that’s a pretty wide loophole – there’s an unlimited set of things happening in London or made in London (much of the UK’s TV is made in London). So for London Live this sounds like a dream – a free slot at the top of the TV guide, you get to run the same shows as BBC, ITV and Channel 4, later. Just like Dave, but at the top of the guide. And yet they still don’t come…

But what about Estuary TV? The law that puts them at the top of the guide in Grimsby also takes away their ability to find a new business model when it turns out that the guide doesn’t bring traffic, and isn’t the future.

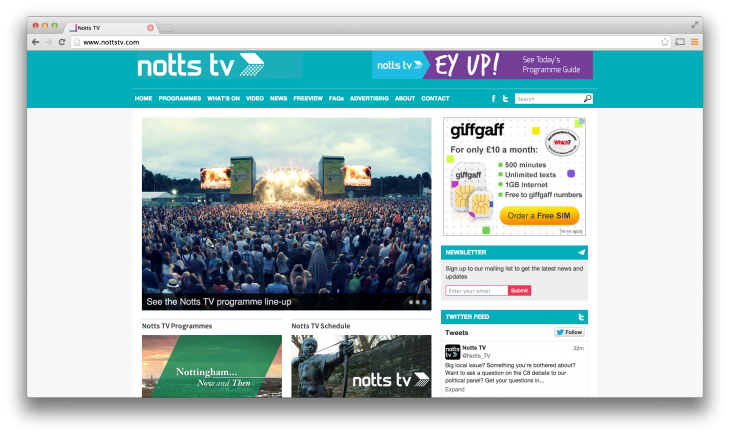

It’s worth pointing out another huge problem with the Government’s plan to deliver local TV in the form of TV channels: Because all local channels share the same single TV channel number, each local channel is available on TV only in its home town or region. This means that Nottingham’s Notts TV is viewable by the million or so people in the Nottingham catchment area, and *not* viewable by the 7 billion people *not* in Nottingham.

That makes local TV useless for local advertisers and businesses included hotels, travel, tourism and anyone with a service to offer to people outside the region. Want to watch a F-Stop, a film “showcasing the very best of Notts’ filmmaking talent”. You can’t. Only people in Nottingham can view it. That’s about as sensible as building a website that only people in your town are able to view.

If instead the Government had helped foster local film making and then worked with local companies to syndicate those shows into global sites where they will be viewed by a global audience in a local context, well, now that’s a model that could be economically sustainable. Sites from the BBC to Trip Advisor, from Google Maps to YouTube, all are high-volume outlets that bring a targeted audience of people not just in that local area, but from around the world.

I don’t know the answer for local TV, but one thing is clear: Government meddling in the incredibly fast moving, innovative tech / media space is bound to end in failure. This new world of innovation is driven by users, by experimentation, by rapid product and business model changes based on analytics and data. Not by legislation.

Also by Anthony Rose: UX designers: Side drawer navigation could be costing you half your user engagement

Image credit: Shutterstock, James Cridland/Flickr

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.