Sifting through the cacophonous crackle of the white-noise Web is becoming an increasingly laborious affair.

It may be something of a truism, but the amount of information and content at our disposal online can be overwhelming at times. 20 million-plus songs on Spotify? Awesome. But I rarely listen to a new album more than thrice these days before I’m being pulled in another direction. This is why Spotify Radio can be appealing, leaving the decision on what music is played to someone (something) else.

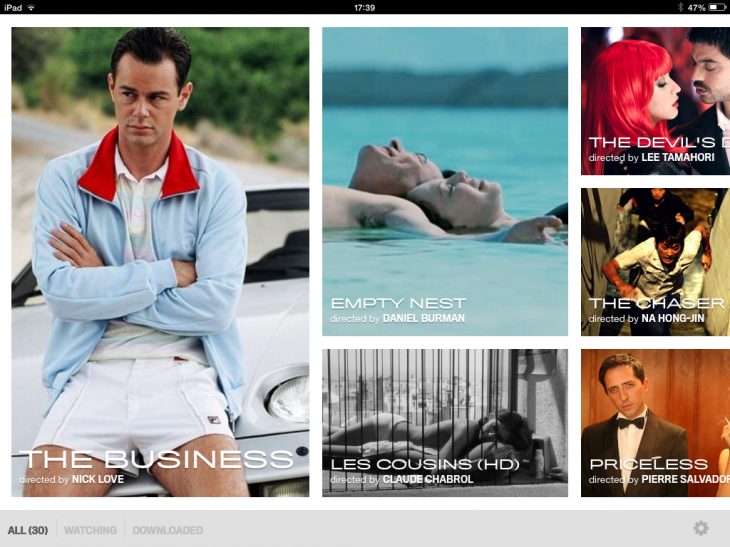

A similar principle applies to video-streaming. Netflix has so many TV shows and movies, it can be difficult deciding what to watch sometimes. I discovered Mubi last year, which is a sort of Netflix for cult, classic and indie movies.

Not only is Mubi great for finding little-known gems from around the world, but it’s highly curated too. Only 30 flicks are available at any given time. There’s enough choice to make it interesting, but only one new film is added a day (with one removed) so it makes the choosing just that little bit easier.

This semi-replicates one of the benefits of traditional linear broadcast TV – you have to watch what the broadcasters decide to broadcast. Choices are limited, sure, but you end up watching stuff you’d otherwise never have seen. And ultimately, it’s devoid of hassle.

We’re now seeing more and more companies tackling this ‘choice overload’ conundrum with their own solutions.

Choosing choices

A new social link-sharing service called ‘This‘ emerged last week, which features a desktop bookmarklet that lets you share only one link each day – basically the antithesis of Twitter.

Then there’s This is My Jam, a music-based social network of sorts that lets you share a single song each day.

It’s all ultimately about encouraging people to really think about what they’re sharing, thereby reducing the noise online and making the Web a (slightly) better place.

Though there are many glorious TED talks out there, one in particular has stuck with me due to its resonance with this information overload situation. Sheena Iyengar is a professor who specializes in research around ‘choice’ – she’s even written a book called the art of choosing.

During her TED talk, Iyengar presented some findings around consumer research they’d carried out around choice overload.

With specific reference to a local grocery store that evidently prided itself on its choice – including more than 75 different kinds of olive oil – Iyengar pondered why she never actually bought anything. After asking the manager if this model worked, they pointed to a bus-load of tourists that would routinely show up to take photos of the store.

But did that mean they spent money, or simply gawped at aisle-upon-aisle of slight variations of the same basic product?

To test a theory, Iyengar and her team used jam, of which the store in question had 348 different kinds. They set up a tasting booth near the entrance, and alternated between offering 6 different kinds of jam and 24 different kinds. It turns out that more (60 percent vs. 40 percent) people actually stopped to engage with the booth when there were more jams available. However, only 3 percent of those who stopped actually bought a jar of jam – but of those who stopped when there were only 6 jars on display, 30 percent went on to buy a jar.

“It turns out that this choice overload problem affects us even in very consequential situations,” says Iyengar. “We choose not to choose, even when it goes against our best self-interests.” Indeed, further studies involving retirement saving plans also showed that the more funds offered, the lower the participation rate.

The psychology of consumption makes for interesting reading, and the basic principles behind many of the theories relating to choice can be applied across many industries.

Prior to the completion of the Microsoft deal, I previously argued that Nokia launched way too many different handsets in a relatively short period of time.

“While Nokia has a bunch of other devices under its Asha label, it’s clear Lumia has emerged as its flagship brand. But it’s a brand that spans so many different devices, features, form factors, and unmemorable version numbers that don’t make any kind of chronological sense to the general consumer. It’s become increasingly difficult for even the most watchful of technophiles to remember exactly what’s what.”

Juxtaposed against the singularity of Apple’s iPhone, which is traditionally launched in batches of one or two devices each year, it’s clear to see why simplicity works. It’s not a debate about what are the best devices, it’s that marketing one or two phones at a time is much easier than marketing 10, and makes it easier to communicate a message.

Faced with so many choices, consumers can get stressed to the point that they simply don’t make a decision.

Many of the big tech companies recognize this too, as content discovery becomes increasingly difficult. This year alone, Google snapped up curated playlists platform Songza, Samsung acquired curated video service Shelby.tv, and Warner bought Spotify playlists-sharing platform ShareMyPlaylists.

It’s not just about digital content either. Many bespoke delivery services promise to take the hassle out of deciding what to buy by deciding for you – just look at Flaviar’s booze subscription offering.

What all the aforementioned services do is strive to make decisions easier for the end-user. They cut through the noise and promise to surface the best articles to read, songs to hear, movies to watch or rum to drink. Sometimes it’s peer-to-peer, sometimes it’s actual ‘experts’ at the helm – but the goal is the same.

It may be a cliché, but sometimes less really is more.

Read next: Why we crave human-curated playlists

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.