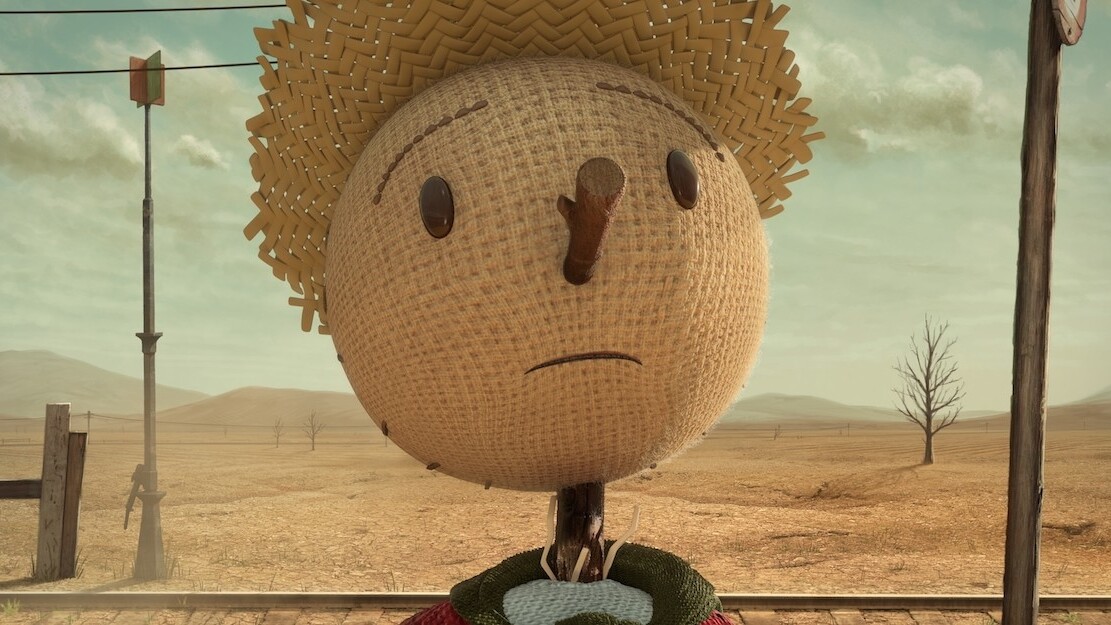

Last fall, we witnessed what select tech press called “one of the most successful marketing campaigns in history.” To promote its Food with Integrity campaign, Mexican fast food giant Chipotle developed an arcade-style mobile game that guided users through 4 worlds and 20 levels.

Users who unlocked all game worlds with at least one star at each level gained entry into Chipotle’s buy-one-get-one offer at one of 1500 international locations.

The Scarecrow film gained 6.5 million YouTube views in less than two weeks, and the chain saw its sales spike in Q1 2014. The game also took top honors at this year’s Cannes Lions festival, winning two Gold awards and one Grand Prix.

But some beyond the marketing realm remain less enchanted.

Advergames – electronic games used to advertise products, brands or organizations across social media, company websites and mobile apps – are growing across global markets. But scholars and policy makers question their role in pushing unhealthy food and drink products to unsuspecting audiences.

They argue that these games exploit a legal loophole that bans the advertisement of such products to children through traditional media, but fails to address more innovative tactics.

The effects on young gamers

This loophole made waves last month when Bath University’s Institute for Policy Research published a policy brief on the impact of advergaming on young audiences. The brief’s co-authors, Dr. Haiming Hang and Dr. Agnes Nairn, found that within the UK market, advergames are most likely to market high salt, sugar and fat (HSSF) food and drink products to young audiences.

Their research also found that kids as old as 15 were unaware that advergames serve as advertisements, or that their eating habits changed without conscious awareness.

These results confirm earlier research from their peers. A separate report released last December by Berkeley Studies Media Group found that advergames are frequently released by food companies to instill brand loyalty in children.

This, in an era where 38 percent of toddlers have used a tablet or smartphone before speaking in full sentences, and 75 percent of children under the age of eight have accessed these devices.

Dr. Emma Boyland, a researcher in appetite and obesity at the University of Liverpool, has seen the impact of HSSF product advertising on children firsthand. The results of her research leave her far from optimistic about the magnitude of mobile.

“Our studies here at the University of Liverpool have shown that television food advertising affects food preferences, choices and actual consumption,” Dr. Boyland explains. “Specifically, after exposure to television food advertising, children demonstrate an increased preference for fat and carbohydrate-rich items, and are more likely to choose such items from the range of foods available.

“They also will eat more, and these effects have been shown in all children, but the greatest magnitude of effect is seen in children who are already overweight or obese and children who habitually watch a lot of television. Also, importantly, these effects are seen not just for the foods being advertised, but for energy-dense (i.e. caloric) foods in general.”

Not their first instance

The exact moment when brands integrated into games is unknown, but advergames are far from new. The term was first used in 2000 by Anthony Giallourakis, although brands ranging from Samsung to Chef Boyardee had developed floppy disk advergames well before then.

In 2006, Burger King began offering one of three video games with its value meals for an extra $3.99; the King Games series helped BK see a 40 percent profit increase that year. The evolution towards iPhones and tablets has increased the attraction of this medium for marketers.

“Advergames are a marketing dream, due to the perfect storm of mobile, social and digital,” says Dan Sodergren, Founder and Leader Trainer of Great Marketing Works. “As the costs of simple game development have come down, [the number of] people who have consumed digital games from birth has increased.

“Such demographics are married to their smart phones, need instant gratification, desire graphically rich feedback and have a cultural belief system around the psychological interactions in games.”

The side effects of disguised advertising

Those interactions come with consequences. Today, more than a quarter of all UK children are overweight or obese, and talk of a sugar tax to combat the problem stands at odds with the lack of regulation on advergaming. The Bath University policy brief alleges that the UK government bans advertising of HSSF products to children on television, but even that is a blurred line.

Dr. Boyland clarifies that the UK government has seen some success in its efforts to limit advertising of HSSF foods during children’s programming, but argues that the law has minimal impact. Like advergames, prime time programming often advertises HSSF products – and young audience members see these ads in droves.

“[The UK regulations] have had some positive effect on dedicated children’s programming, but do not tackle the advertising around television programs that kids watch in greatest numbers,” Dr. Boyland explains. “[On] general entertainment/family programming such as soap operas and X-Factor, the majority of ads are still for unhealthy products.”

Even if children failed to watch such programming, not all are convinced that adults remain immune to the effects of HSSF advertising. Dr. Hang argues that the cognitive impact on eating behavior is more damaging for children.

But his co-author, Dr. Nairn, says that the integrated nature of advergaming means the medium in itself is a problem for all players.

“Advergames are processed by using our implicit processing functions, which means that older children and adults are not ‘protected’ by cognitive capabilities,” Dr. Nairn argues. “It is precisely because advergames, product placement and other immersive and non obvious advertising is processed implicitly that it affects people of all ages the same.

“Adults, of course, have a bit more savvy about the way the commercial world works – but this does not mean that they engage different methods of processing.”

Regulating advergames

As is often the case, mobile ad advancements are outpacing the law. Adventurize.com lets businesses place ads in online games including Minecraft, a popular game amongst the young.

LoopMe Media, a London-based startup, places ads into an inbox that users can then vote up or down. And Future Ad Labs works with clients including Nestle and Heinz to reform online captchas by playing branded games in lieu of typing hard-to-read text.

“It is hard to know if advergames per se have grown in popularity, as the market for them is not tracked,” Hairn tells The Next Web. “However, if you look at the IAB website, you will find reports which show that digital and mobile advertising has now outstripped TV ads. Mobile in particular is growing extremely fast, and this is a medium that lends itself to gaming.”

The IAB website boasts several research reports on the status of game advertising. But its mobile phone creative guidelines date back to 2012. A search for guidelines on gaming advertising leads to one report released in 2010, and their statement on Q1 2014 U.S. Internet ad revenue makes no explicit mention of revenue from advergames.

Startups and researchers alike are troubled by the lack of industry regulation. The Bath University policy brief questions the impact of self-regulation and argues that an independent council ought to oversee global marketing to children across all media platforms.

Howard Kingston, co-founder and CEO of Future Ad Labs, says his startup works with nine brands right now, four of which are food companies. He told me his team takes advertising regulation very seriously, and believes that brands have a duty to comply with regulations that promote positive public health (disclosure: Kingston is my former General Assembly London Digital Marketing instructor).

Stephen Upstone, CEO of LoopMe Media, concurs. He says the broad audience that plays mobile games means that advergaming is the future of advertising that brands should, and most likely will, embrace.

However, he also believes it is the duty of the trade bodies that regulate his business, such as the MMA and the IAB, to set forth clear guidelines for brands and businesses to comply with.

“The policy implications refer the the UK and our specific form of self and co-regulation, but the self regulatory framework which derives from the International Chamber of Commerce is followed in most developed markets even if the legislative framework is not the same,” Dr. Hairn clarifies.

“Given that the internet does not respect international boundaries, a major challenge is to have policies that are applied globally.”

No right answer… yet

With such laws yet to take effect, it is anyone’s guess when they will take hold. In the meantime, there are gaming opportunities beyond the HSSF space.

Years before “The Scarecrow” taught Chipotle fans about sustainable farming, the United Nations World Food Program developed its Food Force game to simulate food delivery in the event of an emergency. Sodergren cites it as a symbol for how advergaming itself isn’t the problem – and stifling ad startups isn’t the answer.

“Laws [and] governments have to catch up with today’s society and consumers,” Sodergren says. “When the [television advertising] law was made, there were no effective mobile games for marketing.

“However, advertising in games and the creation of advergames is one right of revenue that we cannot deny the army of creative and marketing people that produce such bodies of work. To do so stifles a whole industry and throws the baby out with the bath water.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.