Kaspersky on Monday published an extensive report identifying and detailing a sophisticated espionage campaign pushing malware since May 2007. The spy operation targeted “several hundreds” of government and diplomatic organizations mainly in Eastern Europe (especially former USSR Republics) and Central Asia, but also in Western Europe and North America.

Among the victim organizations were embassies, consulates, trade centers, nuclear research centres, as well as oil and gas institutes. The vast majority of infections were based in Russia (Kaspersky identified 35), followed by 21 in Kazakhstan, 15 in Azerbaijan, 15 in Belgium, and 14 in India. Six infected machines were found in the US.

“During our investigation we’ve uncovered over 1000 unique files, belonging to about 30 different module categories,” Kaspersky’s report stated. “The attackers managed to stay in the game for over five years and evade detection of most antivirus products while continuing to exfiltrate what must be hundreds of terabytes by now.”

The malware the attackers use is highly modular and customized for each victim, who is assigned a unique ID so that each module he or she receives is tailored to them. Each module is designed to perform various tasks but the end goal is to steal a variety of documents, including PDF files, Excel spreadsheets, CSV files, and ACID files. The last one is key: the attackers engineered their malware to steal files encrypted with Acid Cryptofiler, an encryption program developed by the French military now used by several countries in the European Union and NATO to encrypt classified information.

The malware doesn’t just extract files (including those that have already been deleted), but also snatches emails, records passwords and keystrokes, takes screenshots, as well as steals browsing history on Chrome, Firefox, Internet Explorer, and Opera. The main objective is to gather as many sensitive documents as possible, and to do anything to make that easier. In fact, some of the modules are plugins for Microsoft Office and Adobe Reader that help the attackers re-infect a machine if the threat is detected and removed by antivirus scanners.

The threat also grabs contacts, call history, calendars, text messages, and browsing history from smartphones, including iPhones, Android phones, and Windows Mobile devices (specific manufacturers Nokia, Sony Ericsson, and HTC were also named). The attackers steal documents during specific timeframes, at the end of which a new module configured for the next timeframe is sent down from the attackers.

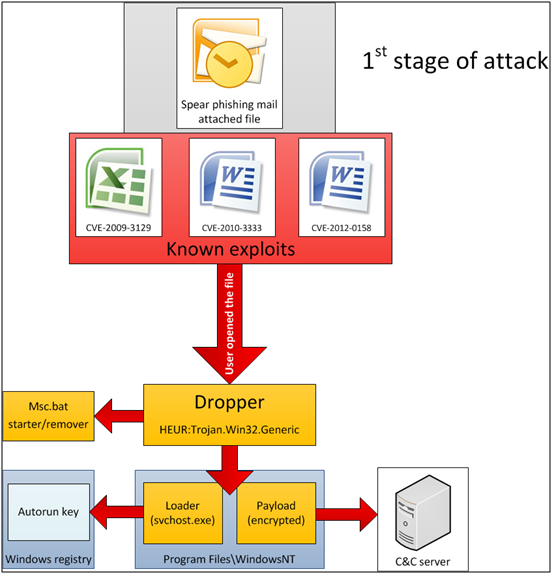

Despite the malware’s sophistication, Kaspersky said the attackers’ methods used to infect systems are very basic: they use a simple spearphishing attack, sending malicious emails to people within the targeted organizations containing malicious Microsoft Excel or Microsoft Word documents. Upon execution, the documents gave the attackers full access to victims’ machines through well-known security exploits; though it’s not clear if this was done out of laziness or in an effort to hide the bigger picture of the massive campaign.

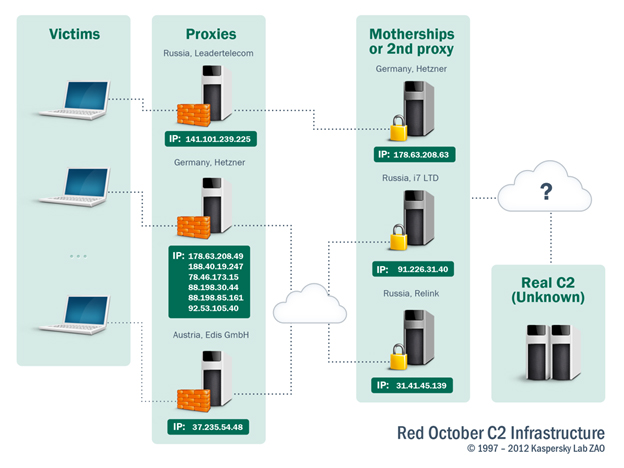

Kaspersky said the attackers used more than 60 domain names and several server locations (mainly in Germany, Russia, and Austria) to manage the network of infected machines. Yet all the command-and-control (C&C) servers are set up in a chain with three levels of proxies to hide the location of the “mothership” and prevent investigators from tracing back to the final collection point where all the stolen documents, keystrokes, and screenshots are processed:

The security firm said it believes the perpetrators were Russian-speaking, but that they likely were not supported by a state. Instead, the criminals are probably looking to sell the valuable intelligence to governments and others on the black market.

Researchers discovered several Russian words embedded in the malware’s code. For instance, the word “zakladka” which can mean “bookmark” in Russian (and Polish), but can also be a Russian slang term meaning “undeclared functionality” or a “microphone embedded in a brick of the embassy building,” appears multiple times. The word “proga,” another term common among Russians which means program or application was used frequently as well.

The company said it named the campaign “Operation Red October” (Rocra for short) after the Russian submarine featured in the Tom Clancy novel The Hunt For Red October, because one of its partners passed on a sample of the malware in question back in October. Since then, the security firm has been finding variations of the malware, with the earliest created in 2007 and the most recent component having put together as recently as last week.

Image credit: Srinivasan Murugesh

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.