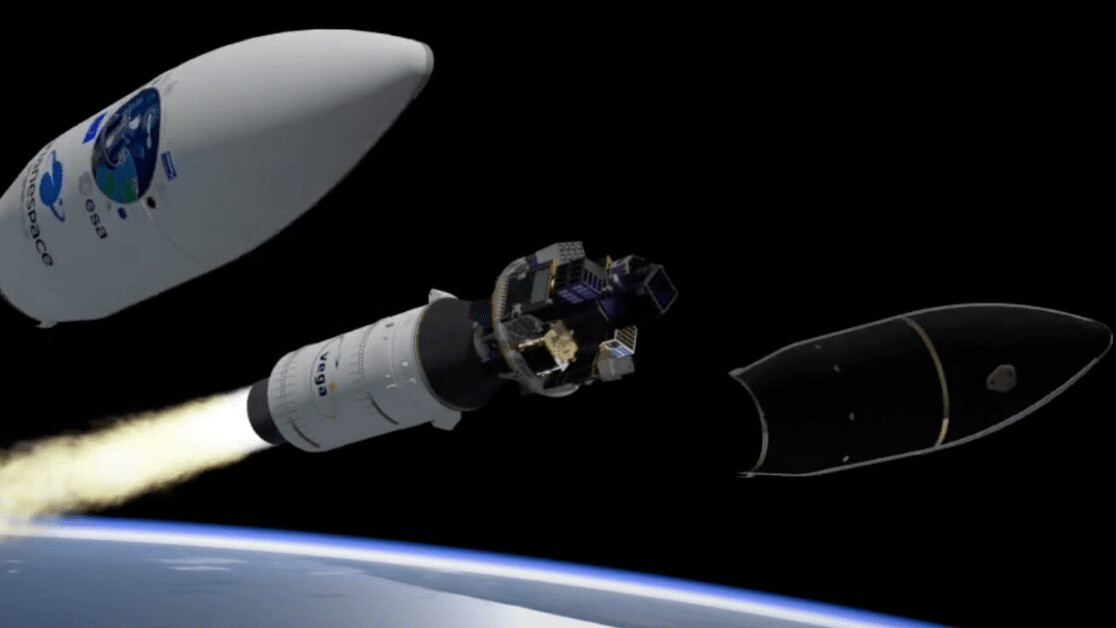

On September 2 in French Guiana, an AI satellite was launched into the Earth’s orbit for the first time in history.

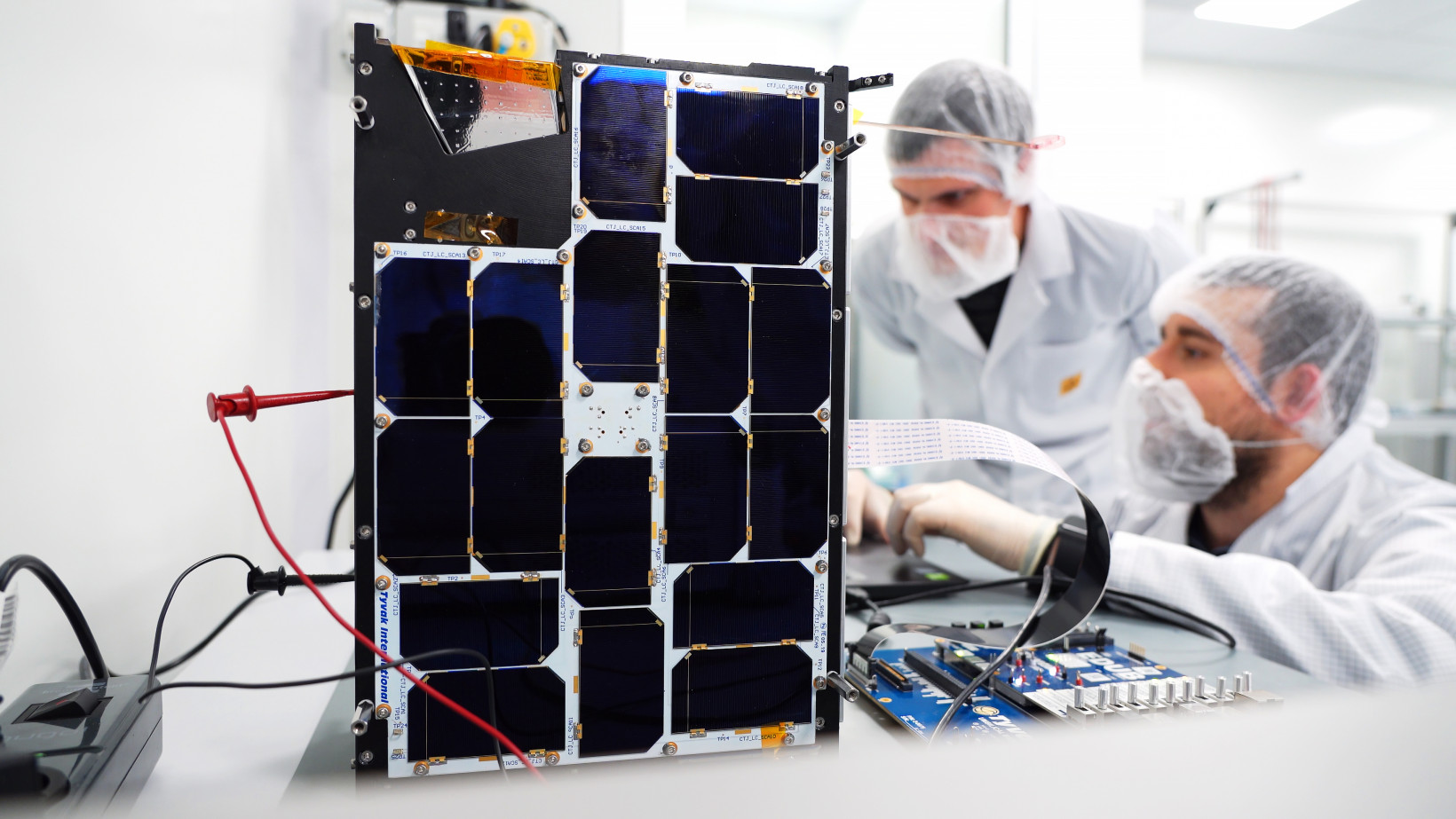

PhiSat-1 is now soaring at over 17,000 mph about 329 miles above us, monitoring polar ice and soil moisture through a hyperspectral-thermal camera, while also testing inter-satellite communication systems.

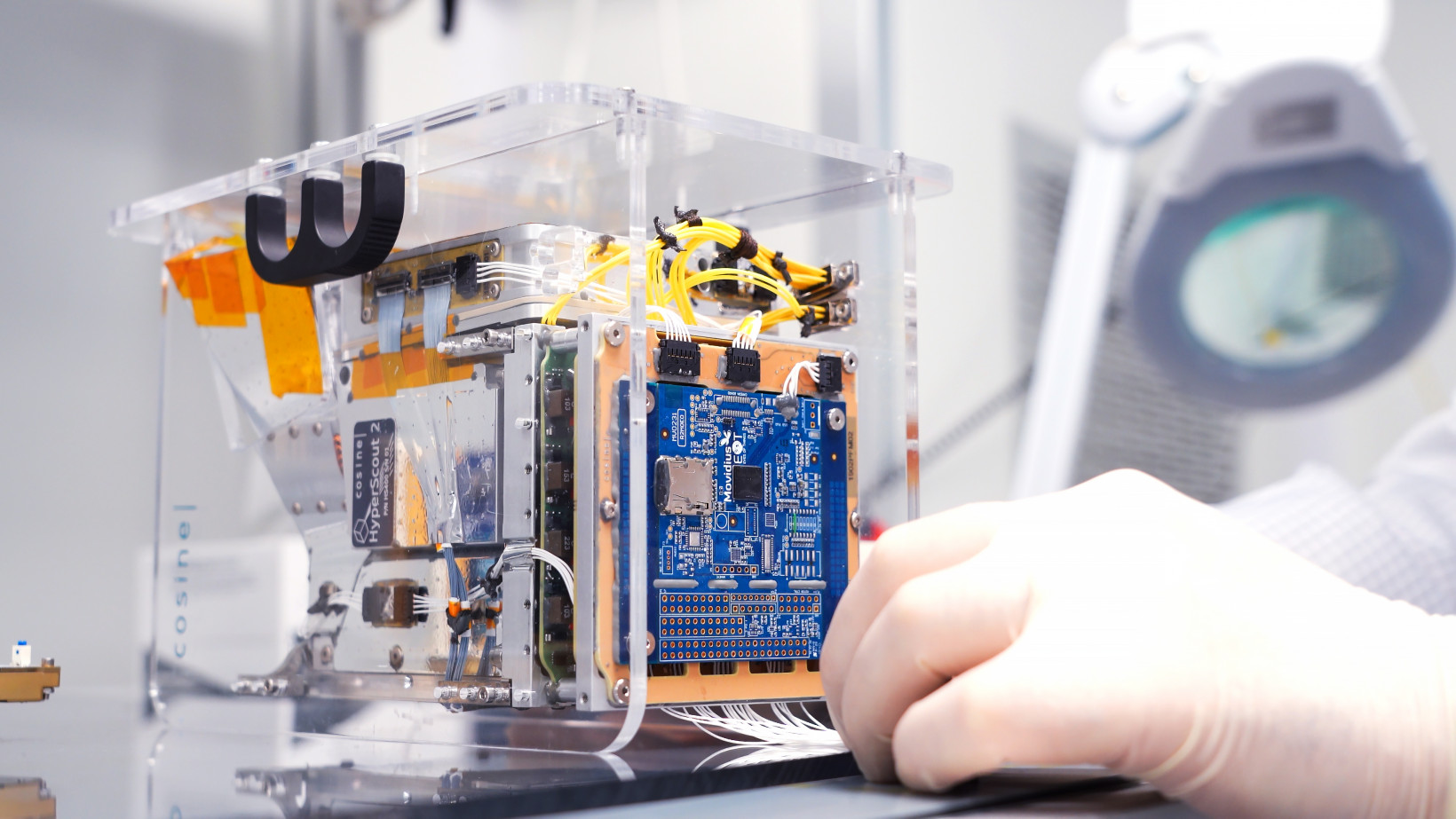

Onboard the small satellite is an AI system developed by Ubotica and powered by Intel’s Myriad 2 VPU — the same chip inside many smart cameras, Magic Leap’s AR goggles, and a $99 selfie drone. Its first task is filtering out images of clouds that impede the analysis.

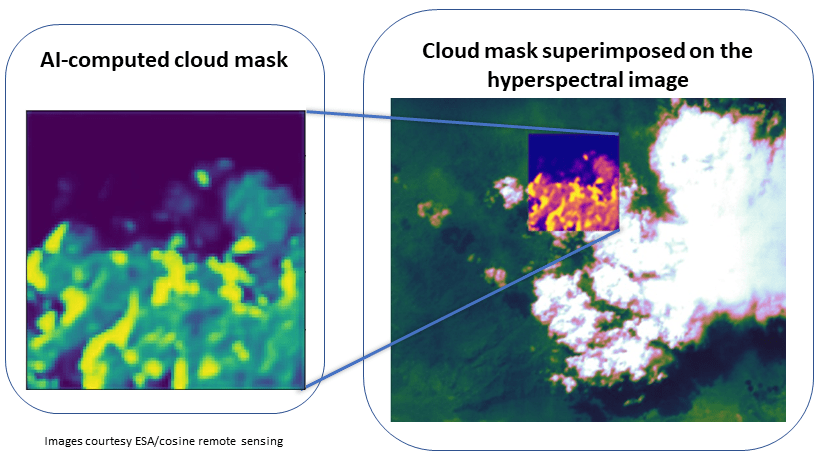

Clouds cover around two-thirds of Earth’s surface at any given moment, which can severely disrupt the system’s analysis.

“Currently, in every satellite bar PhiSat-1, those images are all stored and then downlinked to the earth, because there’s no way of knowing the value of the data until it’s on the ground, and some human can look over them and say that’s valuable and that’s not,” Aubrey Dunne, chief technology officer of Ubotica, tells TNW.

“In the case of PhiSat-1, the AI is doing data reduction by saying there’s a lot of cloud in an image, there’s no point in storing it on the satellite and then downlinking it to the ground for someone on the ground to say that’s just cloudy, throw it away.”

[Read: AI to help world’s first removal of space debris]

The PhiSat-1 team estimates that the onboard processing will cut bandwidth by about 30% of bandwidth and save a lot of time for scientists on the ground.

“This is a huge saving, and this really is just the low hanging fruit for AI,” says Gianluca Furano, data systems and onboard computing lead at the European Space Agency (ESA), which is leading the project. “It isn’t really even our primary objective.”

Other big impacts the system could have are reducing latency and increasing autonomy. AI could quickly detect fires in images and then alert the relevant authorities of the location and size of the blaze, or help Martian rovers avoid craters without first communicating with analysts back on Earth.

Furano says current Martian rovers can hypothetically run some hundred meters per day. But in reality, the need to relay imaging information to and from Earth keeps their range to just one or two meters per day.

“If we can get Martian rovers moving at 10 or 20 times the speed, the amount of science that can be done is enormous,” he says.

Next steps for AI in space

PhiSat-1 is currently in a commissioning phase in which all the system’s elements are being tested. But the team has already got some early results: the first AI inference performed in-orbit.

When the commissioning period ends, a year-long operational phase will begin, with the satellite targeting certain locations on the globe and capturing, processing, and downlinking the relevant image data.

In the future, the AI model onboard could be adapted to perform a range of other tasks. Dunne believes this could lay the foundations for a “satellite as a service” model in which a satellite is deployed with AI hardware onboard that’s rented out for different uses.

“Ultimately, we think it’ll probably get to that point,” he says. “It won’t be tomorrow, but PhiSat-1 will start to prove that this is possible.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.