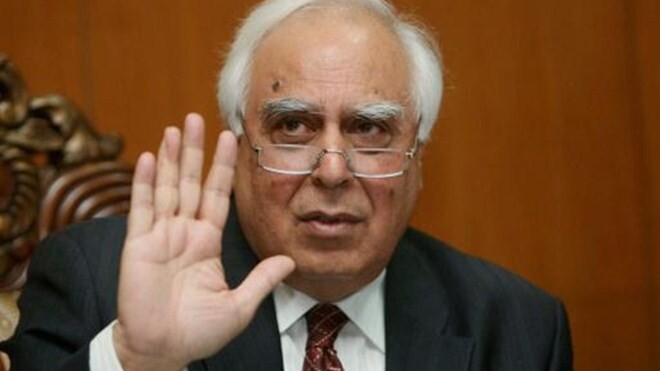

It has been quite a week for social media in India. Monday saw the New York Times reveal that acting telecom minister Kapil Sibal was seeking to pre-screen social media content in the country, however comments from Sibal suggest that it may have been mistaken.

The article alleges that Sibal was involved in dialogue with executives from Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and Facebook in a bid to introduce a very unlikely system that would see all content verified before appearing online.

However, Sibal has spoken up on the issue and refuted many of the allegations in an interview with NDTV in which he discusses the NYT report, issues of the law in India, pre-screening and next steps.

On the New York Times article

While he did admit that the basis of the article had foundation, as India is seeking to have certain content removed, Sibal is defiant that the article takes events out of context. He also admitted that he is disappointed that he was not able to tell his side of the story:

A newspaper of this stature should have contacted me first, they should have sought my comment before making a comment like that.

No plan for pre-screening content

Much of the controversy surrounding this issue has stemmed from the allegation that Sibal is looking to have companies pre-screen content before it is published online.

According to the NYT article, Sibal expected the Internet firms “to set up a proactive prescreening system, with staffers looking for objectionable content and deleting it before it is posted”. He, however, denies the claims:

People would be mad to say that there could be pre-screening of content.

We have no intention of censorsing or pre-screening, but [India] has to be concerned at the kind of content that is floating around online.

This is without a doubt the most significant aspect of the issue. Though the NYT article does not quote him directly, the sources at the Internet companies clearly believe that he is pushing for pre-screening, but his comment is a flat out denial of this.

Ultimately, it is difficult to know what to believe. There is little accountability of the source comments, as they are anonymous, while there is no evidence of exactly what Sibal’s intentions initially were before the issue becoming an international talking point.

For most people, whether Sibal is to be believed, is likely to be down to their own opinions of him. Going on the interview, it is plausible that the actual events were taken out of context by the NYT article and its sources.

No censorship of political content

The report, combined with Google’s Transparency Report, led to suggestions that the pre-screening might be a tool to prevent criticism of the government in India. According to the report, which is an annual account of all government requests to remove content from Google, more than 70 percent of the items put forward in India were around political content.

Here’s what Google had to say about India in the overview of the report:

We received requests from state and local law enforcement agencies to remove YouTube videos that displayed protests against social leaders or used offensive language in reference to religious leaders.

We declined the majority of these requests and only locally restricted videos that appeared to violate local laws prohibiting speech that could incite enmity between communities.

In addition, we received a request from a local law enforcement agency to remove 236 communities and profiles from orkut that were critical of a local politician. We did not comply with this request, since the content did not violate our Community Standards or local law.

In response, Sibal denies that his office was behind the majority of these requests, though he admits that it did file “three or four” requests, none of which were not granted. He points to the fact that Google does not disclose the sources of the request, which could be made by any branch of the government or authorities, as evidence that the telecoms ministry is not pursuing a political agenda.

As for the suggestion that the censor push is related to political criticism, Sibal says his team “have not taken any steps to gag people”, as the content highlighted by the government was “mostly religious”.

Furthermore, Sibal claims that high profile figures should be able to tolerate comments about them online, while he believes that satirical criticism of government figures is allowed under freedom of speech. Those that are defamed by Internet comments can turn to the legal system to follow up, he says.

Existing laws are “broken”

When pressed to explain why the government had not used India’s legal system to take down the content, Sibal explains that the route would be difficult and may take years to complete:

[The Internet companies] are only carriers, we can’t sue them as they not responsible for the content, and they will not tell us who the source of the content is, so we can’t sue [the end users] either.

The global scope of the Internet allows anyone from across the world to post content that may breach laws or standards of decency in another country, which means tackling offending material is not always straight forward.

While other countries chose to block offensive content, Sibal — who is a lawyer by profession — believes a new system is required to plug this gap:

Global standards and a consentual mechanism will need to be evolved, so that everybody stands by the rules that content that is not acceptable in any civil society will should not be uploaded.

So what will be done going forward?

Sibal is planning to host a round table for one final push to work with Google, Facebook and others to fix the issues. He has openly invited media and is hoping that, with this meeting in place, a solution to monitor and deal with content will be discussed and a plan will be put forward.

In the event that the Internet firms are unable to push things on, the government will explore other options, as he outlines:

This is business in progress. We will evolve a consensus and, if the sites still don’t accept it, then we will have to do something about it [as] this kind of content should not be in the public arena.

Comment from Google and Facebook

A great many number of people passed comment on Sibal’s alleged aims with the censorship. While the US Embassy felt so compelled to contact Sibal’s office, the comments from Google and Facebook — two companies at the centre of the controversy — are most telling of their stance on the situation. It is also worth noting that there is no mention of, or reference to, the issue of pre-screening – might that indicate that it wasn’t discussed, or did neither company feel the need to respond to it?

Here’s what Facebook said to CNN about removing content in India:

We want Facebook to be a place where people can discuss things freely, while respecting the rights and feelings of others, which is why we have already have policies and on-site features in place that enable people to report abusive content.

We will remove any content that violates our terms, which are designed to keep material that is hateful, threatening, incites violence or contains nudity off the service.

We recognize the government’s interest in minimizing the amount of abusive content that is available online and will continue to engage with the Indian authorities as they debate this important issue.

Google’s stance was somewhat different, as the search engine giant told Economic Times, it has full confidence in its existing moderation system:

We work really hard to make sure that people have as much access to information as possible, while also following the law. This means that when content is illegal, we abide by local law and take it down.

And even where content is legal but breaks or violates our own terms and conditions we take that down too, once we have been notified about it, but when content is legal and does not violate our policies, we will not remove it just because it is controversial, as we believe that people’s differing views, so long as they are legal, should be respected and protected.

Conclusion

India remains a key focus for a number of Web companies — Facebook, for example, forecasts that it will soon become its biggest market — but none are likely to be impressed by the events of this past week, which has thrown up a number of issues in India.

Sibal has been widely criticised from inside the country, and the world over, for not understanding social media but, going on his interview, it appears that the reporting of his overall intentions may well be inaccurate.

From the NYT story and its sources, it is clear that the companies concerned are also equally confused as to India’s aims. If Sibal’s latest dialogue is to be believed, they may well be more cooperative as neither pre-screening nor political topics will be on the agenda.

We’ve reach out to the New York Times for comment, as we try to dig deeper into this story. We’ll update this post with any response it provides.

What do you think? Did the New York Times report the situation out of context, or has Sibal simply backtracked on his initial plan after the public backlash? As ever, we look forward to your thoughts in the comments section.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.