Species living on land make up 85 percent to 95 percent of all biodiversity on Earth today. This is especially impressive when we consider that the continents cover only 30 percent of our planet’s surface area. And that most land species are descendants of a small number of pioneering groups that invaded the land about 400m years ago.

Surprisingly, though, scientists strongly disagree about when land biodiversity reached modern levels. Is what we see today typical of the last several tens, or even hundreds, of millions of years? Or has diversity been increasing exponentially, with substantially more species alive today than ever before?

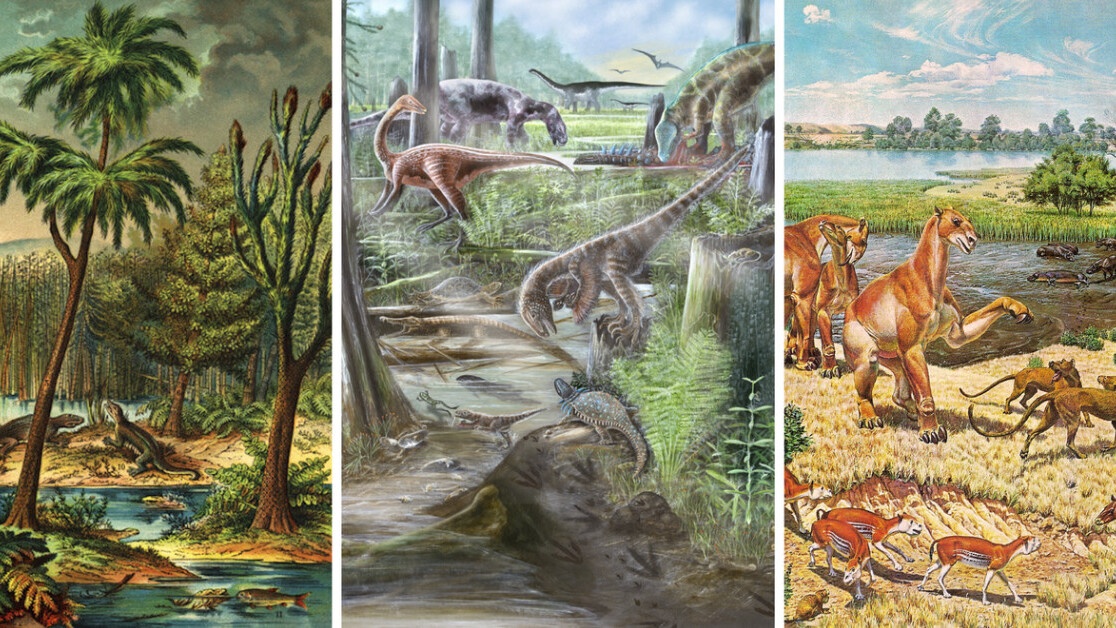

In a new paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution, my co-authors and I examined how the diversity of land vertebrate species living in “local” ecosystems (also known “ecological communities”) changed over the last 375m years. We analysed nearly 30,000 fossil sites that have produced fossils of tetrapods, land vertebrate animals, such as mammals, birds, reptiles (including dinosaurs) and amphibians. Counting species within individual fossil sites allowed us to estimate the diversity in ancient ecological communities.

Our results show that the rich levels of biodiversity on land seen across the globe today are not a recent phenomenon. Diversity within tetrapod ecosystems has been similar for at least the last 60m years, since soon after the extinction of the dinosaurs. This suggests that the prominent idea that biodiversity within ecosystems rises more or less continuously over time is incorrect. Instead, it’s likely that the way species interact – for example, by competing for resources such as space and food – tends to limit the number of species that can be packed into local ecosystems.

That doesn’t mean that local diversity in tetrapods hasn’t increased over the course of the last 375m years. Our results also show that this diversity is at least three times higher today than it was around 300m years ago, when tetrapods first evolved key innovations for life on land (such as the amniotic egg, which allowed reproduction away from water sources). However, we discovered that increases in diversity are rare and happen relatively abruptly in geological terms. They are also usually followed by tens of millions of years when no increases occur.

Counterintuitively, the largest increase in local diversity took place after the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs, 66m years ago. Within only a few million years of this event, local diversity had increased by two to three times over pre-extinction levels, largely thanks to the spectacular success of modern mammals, which evolved to fill the ecological space left by the dinosaurs. But after this large rise, local tetrapod diversity didn’t increase over the next 60m years.

Different scales

The competing models of animal diversification make clear predictions about how diversity at the local scale should change over geological time, with either long-term stability or continual increases. By demonstrating that there are limits to local diversity that persist for millions of years, our results pose a challenge to models that show diversification continues more or less unchecked. But diversity at the continental or global level could follow a separate pattern, so our results don’t necessarily apply at these scales as well.

For example, following a mass extinction, most species on a continent could be wiped out. But a relatively small number of surviving species could become very successful and spread widely. In this scenario, diversity over the whole continent would crash, but local diversity could appear to be unchanged because the same small set of species would be found everywhere.

In fact, a similar process appears to be happening now in response to habitat destruction caused by humans. Invasive species are spreading widely, sometimes pushing up local diversity even while regional diversity may be falling. But previous work by my research group on continental-scale land vertebrate diversity in the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic eras (around 250m to 47m years ago) suggests that, over long timescales, species counts within continents show a similar pattern to those at the local scale. This means that the spectacular diversity on land today – at least within vertebrates – is probably not a recent innovation.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Roger Close, ERC Research Fellow in Palaeobiology, University of Birmingham under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.