For the ongoing series, Code Word, we’re exploring if — and how — technology can protect individuals against sexual assault and harassment, and how it can help and support survivors.

Imagine it’s your first time entering a social virtual reality experience. You quickly set up an avatar, choosing feminine characteristics because you identify as female. You choose an outfit that seems appropriate, and when you’re done, you spawn into a space. You have no idea where you are or who is around you. As you’re getting your sea legs in this new environment, all the other avatars look at you and notice that you’re different. Strange avatars quickly approach you, asking inappropriate questions about your real-life body; touching and kissing you without your consent. You try blocking them, but you don’t know how. You remove your headset fearing that you don’t belong in this community.

New worlds, old problems

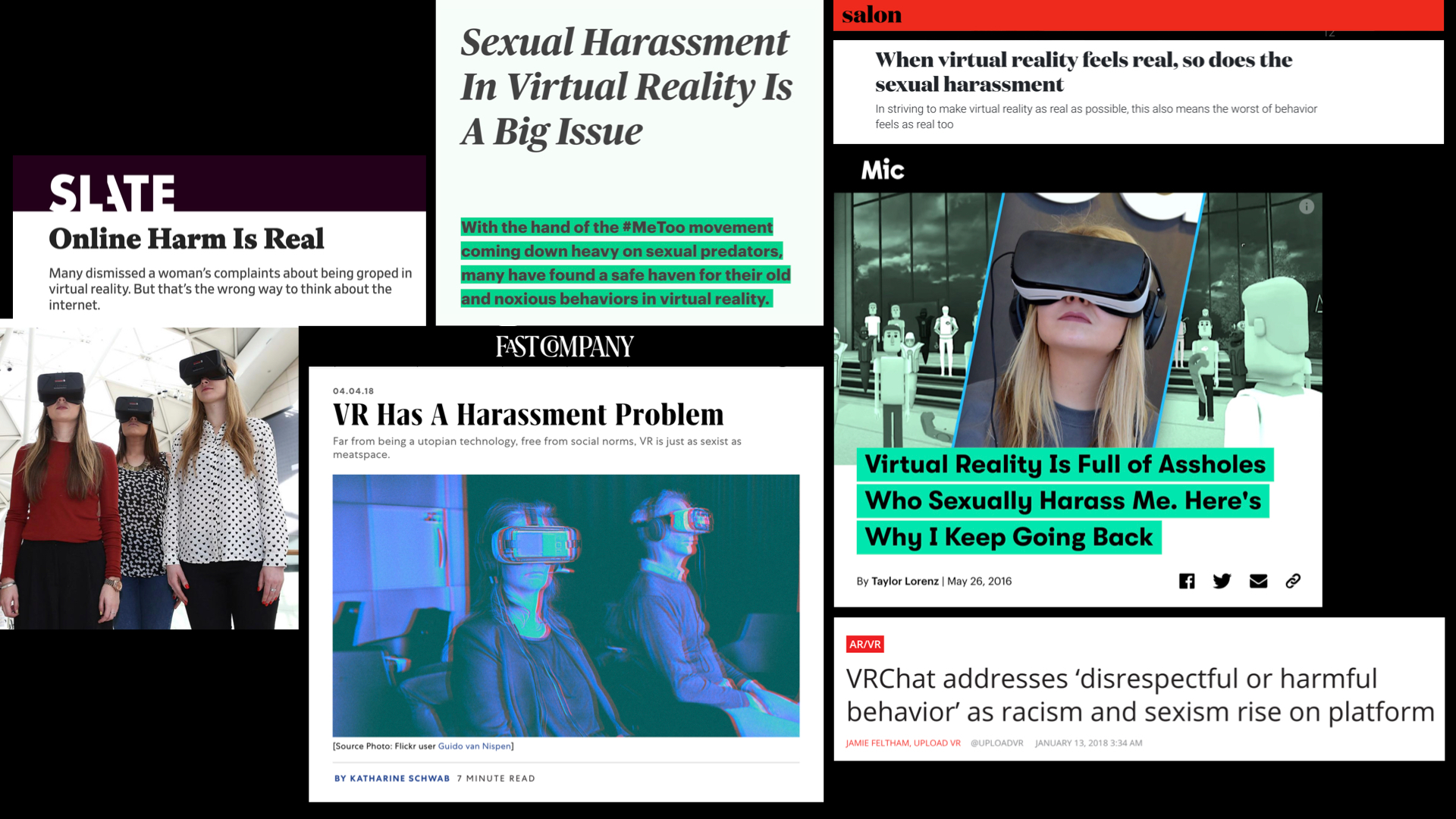

The above role play is based on various accounts of avatar harassment in social VR applications, reported by women in recent years. In 2016, Taylor Lorenz, a staff tech writer currently at The Atlantic, garnered attention from various social VR start-ups by sharing her experience in a virtual reality chat room. In an essay for Mic, she describes being greeted with unsolicited “virtual kisses” and asked about her real-life body by multiple users, noting that she felt ripped from the virtual world and transported back to middle school.

Soon after, VRChat publicly vowed to make safety a top priority after VR game designer, Katie Chironis, shared a graphic recording of sexual harassment in one of their chat rooms. After that, a 2018 study conducted by Jessica Outlaw for VR communication service Pluto, reported that nearly half of the female-identifying VR participants have had at least one instance of virtual sexual harassment. And while these cases are unique in the broader harassment landscape, they are a notable facet of an emerging market.

As female designers working in VR, my co-worker Andrea Zeller and I decided to join forces on our own time and write a comprehensive paper. We wrote about the potential threat of virtual harassment, instructing readers on how to use body sovereignty and consent ideology to design safer virtual spaces from the ground up. The text will soon become a chapter in the upcoming book: Ethics in Design and Communication: New Critical Perspectives (Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London).

After years of flagging potentially-triggering social VR interactions to male co-workers in critiques, it seemed prime time to solidify this design practice into documented research. This article is the product of our journey.

The illusory virtual self

So why did we feel like we needed to take action on social VR harassment? Because when you’re in VR, interactions can feel real. During an early social VR demo, we discovered a bug that caused avatar hands to stick together when two users were in a virtual room. Two participants who didn’t know each other in real-life found themselves holding hands in VR, and when they took off their headsets blushing, as if they really held hands.

This sensation of experiencing a virtual body as your own is called “virtual embodiment.” Take the “virtual hand illusion,” for example — a VR variant of the “rubber hand illusion,” conducted by VR researcher Mel Slater. When a visible rubber hand (or, in this case, a virtually visible rubber hand) is put in front of a test subject, they tend to process potential sensations and threats inflicted on the fake hand as real experiences. This is an example of how the brain can form a connection to a foreign body.

When this happens in virtual space, and someone threatens or violates your virtual body, it can feel very real. This is particularly worrisome as harassment on the internet is a long-running issue; from trolling in chat rooms in the ’90s to cyber-bullying on various social media platforms today. When there’s no accountability on new platforms, abuse has often followed — and the innate physicality of VR gives harassers troubling new ways to attack. The visceral quality of VR abuse can be especially triggering for survivors of violent physical assault.

According to Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, feeling safe is a basic human right — in any place. And since social VR places have many of the hallmarks of real-world social places, we should be to crafting safety into our virtual experiences. It’s important that we do it now, while social VR is still young and the standards are being set. Safety and inclusion need to be virtual status quo. This notion is likely so obvious to us because, as women, we think a lot more about safety in real life.

Don’t believe us? See this Jackson Katz experiment: he asks men and women what they do daily to avoid being sexually assaulted. For women, the list begins with, “Hold my keys as a potential weapon, check the back seat before I get in the car, don’t drink too much, don’t leave my drink unattended, carry mace, don’t have a listed number […]” and continues seemingly indefinitely. While for men, this isn’t something they think about; their go-to answer was, “Nothing.”

We knew that it was important to look at the problem of virtual reality harassment from our unique perspective as women in VR, and we started by looking at consent language. Having written our paper in the year of #MeToo, we had a lot of consent-focused debate in the media to take inspiration from.

We started with primary definitions of consent, such as, “all people should have complete ownership of their bodies and any interactions that should occur to them,” a quote from Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti’s Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power and A World Without Rape(Berkeley: Seal Press). We grew that practice into looking at body sovereignty and ownership as an interactive principle to ensure safe, inclusive social VR spaces and help maintain a healthy virtual embodiment.

Fostering safety in virtual spaces

Well, that’s all well and good, but how do we — as designers — bring consent, body sovereignty, and respect into the virtual world? By empowering people with easy-to-understand social norms, accessible tools, and appropriate behavior engagement. Our theory was that we could develop these features by looking for consent-acquisition paradigms in the real world and proposing virtual equivalents.

To begin this process of digitizing consent, we knew it would be critical to understand how people perceive appropriate behaviors in the real world. In our day-to-day lives, there is etiquette in how we interact with people. You don’t wear your pajamas in public. You don’t skip the line or cut somebody off in traffic. And, if this does happen you can take action to stop that behavior. VR has very similar social modalities to what we experience in our real lives but, because VR is such a nascent format, the social norms we experience in reality have yet to be applied. In order to bring equity to VR would would have to pull in real world conduct expectations.

So, to create codes of conduct for VR, we looked to the factors that make up our real-world environments. Proxemics — a term coined by anthropologist Edward T. Hall — refers to the relationship between your identity, your surroundings, and the social norms of the community around you. Hall divides experiences into zones of distance from the body.

Proxemics can be viewed as four distinct categories: intimate, personal, social, and public. The boundaries of these zones help us understand appropriacy at various distances. In the real world, each zone has an established code of conduct that offers explicit rules for what behaviors are acceptable and unacceptable. We can use these zones to help people understand what behavior is appropriate at specific times and locations.

Using proxemics as a spatial scale, we can define explicit structures for behavior expectations and build natural boundaries in virtual social relationships. In separating these regions, we’re able look at consent acquisition models unique to each and provide VR equivalents, cumulatively building an infrastructure for virtual safety. This results in inspiration for consent introspection, tailored to each zone — the architecture of our code of conduct.

As we go through each zone, we will accompany our inclusive design suggestions with examples from various social VR experiences.

Intimate space

Let’s begin with the nearest zone: intimate space. In the real world, an example of this would be a bedroom. To build safety in intimate virtual spaces, we suggest designers build granular controls that are easy to access and surfaced before intimate interactions begin. It’s important that people can customize and control the types of experiences they’re willing to have with other people in these close quarters before they happen.

The inspiration for this comes from the real-world intimate consent paradigms found in “Yes, No, Maybe” charts. These are procedures — often used by the BDSM community — in which individuals may list all intimate acts imaginable and categorize them into (1) experiences they would enjoy, (2) experiences they don’t ever want, and (3) experiences they’re not sure about. These individuals would then share these lists with each other before engaging in any precarious intimate acts.

In VR, we can empower people by allowing them to define their ideal experience up front, to avoid violation in their digital intimate space. Our example here is from Rec Room, and shows granular controls for interactions within the Experiences tab of the Settings panel. This dialog allows people to define how close other users can get to them by setting the parameters of their personal safety bubble before any interaction happens.

Personal space

Next, let’s look at personal space. In the real world, an example would be a living room or other shared household space.

To build safety into virtual personal spaces, we can look at how medical practices negotiate consent through nonverbal cues. Specifically, we took our inspiration from the way the National Institute of Health secures ongoing consent from deaf participants in clinical trials using universal gestures. Designers should incorporate simple communication gestures and easy-access shortcuts to allow their users quick-action remediation in tough situations. These simple shortcuts can allow users to quickly report a problematic experience without interrupting or further degrading their experience.

We designed the upcoming Facebook Horizon with easy-to-access shortcuts for moments when people would need quick-action remediation in tough situations. A one-touch button can quickly remove you from a situation. You simply touch the button and you land in a space where you can take a break and access your controls to adjust your experience.

Social space

In the real world, an example of a social space could be a college campus. To make social virtual spaces safer, we can refer to the unspoken conduct agreements that keep interactions appropriate in specific environments.

We looked at the rules sets created by colleges to prevent on-campus assault, and how the campuses needed to be explicit for reinforcement of these rules. Designers can introduce local behavior expectations in VR social spaces by creating conduct codes customized to the activities of the space and weaving them into the fabric of the space.

Our example of local behavior codes is from the [now-defunct] social VR app, Facebook Spaces. As people entered a room that belonged to a specific Facebook group, we set expectations for conduct in this space with these rules. Designers can reinforce these sorts of local behavior expectations by administering rewards to users who uphold the rules or report violators.

Public space

And finally, public spaces. In the real world, a great example of a public space could be a public park or an entire city; any place in which you could potentially meet any kind of person. To ensure inclusivity in public virtual spaces, we can look to real-world law systems for inspiration. Specifically the real-world’s definitions of consent, evaluations of public behavior violations, and criminal consequences. We should consider comparably universal rules and persistent consequences for virtual violation and harassment.

For example, VRChat created a universal system (across all their worlds) that defines appropriacy and allows people to report offensive behavior. By pushing timely consequences to violators, these systems reinforce conduct expectations.

More than zones

As VR designers, we hold the unique opportunity to imagine worlds unbound by reality’s constraints. When approaching the responsibility of constructing new social environments — regardless of how surreal they may be — we should remind ourselves to treat virtual embodiment with the same respect given to physical bodies. Even if the real reality we inhabit often fails to do so.

It is our responsibility to design innately safe virtual spaces and interactions, laying the groundwork for a future of inclusive, secure and empowering VR communities — a safe future is in our virtual hands.

This article was originally published on Immerse by Andrea Zeller and Michelle Cortese. Zeller is a virtual and augmented reality communication designer. She began her career as a filmmaker and now designs for Facebook. She helped grow the content strategy discipline to writing beyond the screen at the University of Washington. Her work focuses on applying storytelling and ethical communication patterns to participatory experiences.

Cortese is a Canadian virtual reality designer, artist, and futurist. She splits her professional time between working on Facebook Horizon and teaching at NYU Steinhardt. Most of her work, both art and design, investigates the transmutation of human communication across new technologies and formats.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.