Voice automation is on everyone’s mind this year, and for good reason. Siri, Alexa, and their peers have sparked visions of a science-fiction-like future and generated excitement around their potential to help simplify our lives with a widely accessible, responsive user interface. Yet this technology is still in its infancy.

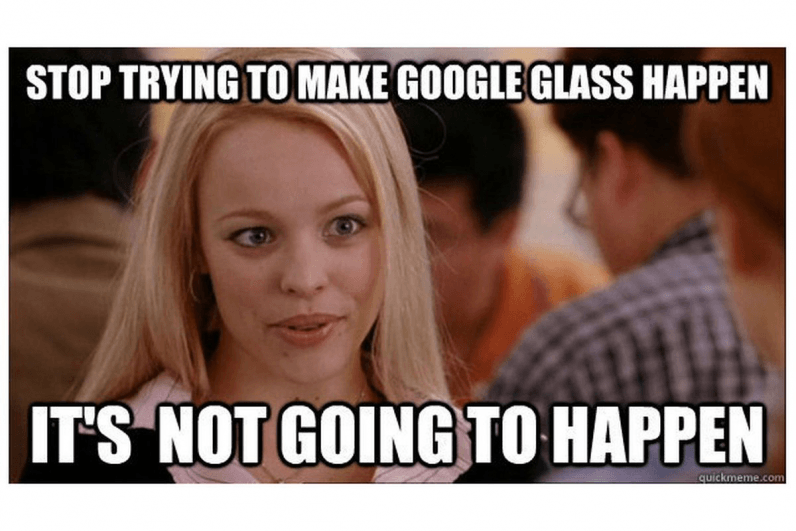

While we’re all intrigued by the possibilities, most people are rightfully skeptical of whether voice applications will live up to their promised potential or crash and burn in the technology hall of shame (alongside a pile of Segways and Google Glasses). While it’s useful to get a news briefing or today’s weather by asking your smart device, do we really need voice devices that mimic a fidget spinner or meow at our cats? (No judgment, cat owners — key word is ‘need’).

We may find it amusing to have Alexa tell a dad joke, but this kind of novelty doesn’t generate rabid user loyalty. The key to creating the kind of passionate adoption that makes people line up outside Apple stores at midnight is an exceptional user experience — one which is not only free of major pain points or frustrations, but also meets unmet needs and creates a feeling of excitement and delight

The prevalence of these issues beg the question: how will people react when voice platforms don’t work the way they’re supposed to or when a device can’t make sense of a straightforward command?

First impressions are critical

So there’s good news and bad news: we’ve seen tremendous enthusiasm for and interest in the technology, but also a relatively low tolerance for frustration with poor experiences. As we’ve observed repeatedly with mobile apps, bad experiences cause users to jump ship. Twenty-five percent of users open a mobile app once and never open it again, largely because of confusing experiences or dubious value propositions. Voice applications face an even steeper uphill climb.

While it’s true that retention rates doubled over the past nine months, that statistic represents a jump from three percent to a whopping six percent. Voice applications have one shot to get it right with users. After a certain number of these frustrations, users may become disillusioned with the voice platform and device altogether. And as with mobile apps, once you’ve lost a user, it’s nearly impossible to regain their interest. Brands entering the voice space can’t afford to fail in delivering a great first experience.

So what to do? The secret to achieving greater user satisfaction and adoption with voice technology is hardly a “secret at all” — namely, create a better experience through user-centered research and design. Sounds simple, but voice technology is a new frontier and so is its design space.

We don’t interact with voice automations in typical environments so more than ever, context matters. Standard ways of conducting UX research (e.g., 1:1 lab-based research, surveys, etc.) may not deliver useful insights around voice, particularly in the early stages of design. We need a more creative approach to how we study what users want and need from their voice experiences.

Context matters more than you think

Consider this: if you were trying to build a better version of PowerPoint, you wouldn’t try to understand how someone uses Office while they’re out at a nightclub. Even if you use PowerPoint daily and visit discos nightly, it’s (hopefully) rare that those two things happen at the same time.

If you’re not typically creating slideshows while Tiesto blares under strobe lights, it doesn’t make sense to ask what you want and need while you’re in the club because your entire mindset is different. (I might use that opportunity to study how you’re using Tinder or Snapchat, but that’s a different article).

The risk here, as with the aforementioned Segways and Google Glasses, is that without considering context, I may solve for a problem that doesn’t really exist. Based on feedback in the nightclub, I might conclude that I should develop a one-handed version of PowerPoint that lets you hold a drink and bust a move while you work on your presentation — but I’d be solving for the wrong problem. In the same way, it doesn’t make sense to only study what people want from voice interactions using traditional UX research methods like lab-based usability studies, and yet that’s what most brands are doing.

Don’t get me wrong — those methods have value and are the foundation of most work we do. They’re time-tested and work very well for many things. But environmental and social cues have a profound influence on our behavior, so to understand what users want and need, you must take context into account. What I’m comfortable asking a voice assistant to do while I’m alone and talking to it in a quiet, controlled lab environment is going to be very different from what I may ask it to do in my home around other people.

To better understand what your users want and need (as well as what they might hate — equally important), study them where they are — whether that be in their homes, cars, offices, or walking on the street. Then turn to traditional lab-based studies to understand how to iterate, refine, and develop the perfect experience. It’s likely that your preconceptions will need to be adjusted once you see users in action… and that’s a good thing! The first step in creating an exceptional voice experience is studying users where they’re going to actually have that interaction: in the real world.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.