Assuming his microphone was off and the camera no longer rolling, the Argentine Finance Minister berated the foreign journalist for asking questions about inflation. “But if I can’t ask you about inflation, who am I supposed to ask?,” the reporter wondered. The minister then muttered the words that would instantly became an internet meme: “I want to get out of here.”

The #YoMeQuieroIr incident and the explosion of online activity that followed says a lot about the current political climate in Argentina.

Though inflation is popularly believed to hover above 20%, the government’s official statistics department insists the rate is only 10%. Any economist who dares publish otherwise faces the threat of government sanction.

The Finance Minister’s response to the question on inflation, “I want to get out of here,” sums up how a lot of Argentines feel about the country’s state of affairs.

And it’s not just inflation that’s getting under the skin of Argentines. Currency controls, spiralling crime, the politicization of the judicial branch and the general malaise with the Cristina Fernandez government has led to protests, partly organized on the Internet, of tens of thousands taking the streets to demand better governance.

It is within this context that a new Internet-based political party has been born: what is unique to this party is that its goal is not necessarily to take power but to change how power is exercised by creating a new ‘front-end user-interface’ for Argentine democracy. As Santiago Siri, Internet entrepreneur and founding member of the movement says, “we want to weave a bridge between the click and the vote.”

“Democracy has stagnated”

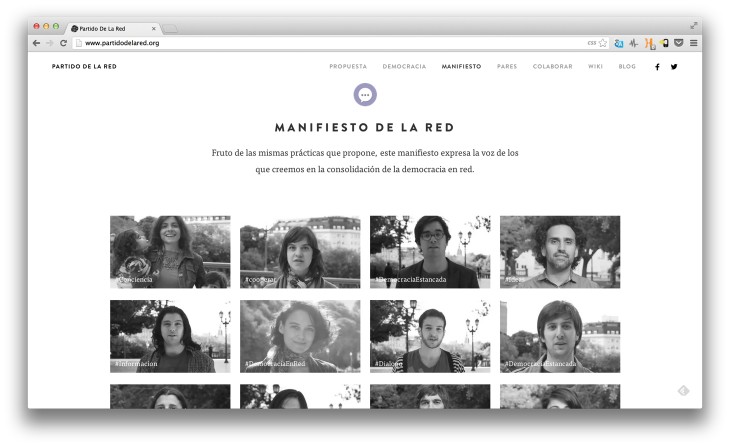

Based on the principle that “democracy has stagnated,” the value proposition of El Partido de La Red, in English The Net Party, is to create a hybrid model of representative and direct democracy in which candidates representing the Net Party are elected to the country’s governing bodies but their vote on any given issue is determined by the collective intelligence of the party’s members.

The members in turn use an open-source software platform to discuss, debate, and vote on the issues before congress. The congressmen, therefore, are trojan horses who are binded to stand by and defend what the party’s collective membership decides.

Unlike traditional political parties, however, the goal of the Net Party is not to govern. “We don’t have pretensions to hold power,” notes founding member Flor Polimeni. “We will be happy if any of the political parties want to adopt our system.”

Like true agents of change, the goal of the Net Party is not necessary to ensure its own success but to bring about wide-scale transformation and create a market for an idea where one currently does not exist.

In this sense success is not measured by whether the Net Party takes over congress, but that the principles of online consultation be infused into all political processes, shifting the balance in representative democracy away from representative and towards democracy.

“We want to democratize democracy”

“Technology,” summarizes Santiago Siri, “has the effect of democratizing everything. We’ve democratized access to culture, to knowledge and information, and now we want to democratize access to power. We want to democratize democracy.”

Despite their ambitions, the Net Party still has a number of obstacles to overcome. As the former Mayor of San Francisco Gavin Newsom noted in his recent book Citizenville, many digital democracy efforts are overrun by special interest groups whose offline organizational capacity allows them to suffocate efforts to engage directly with citizens.

Should the Net Party threaten to win votes it is without a doubt that the cutthroat nature of Argentina’s politics will be turned on the diverse group of political neophytes who may be masters of new media but who will no doubt have to do battle with the masters of old media.

Nevertheless, the Net Party founders remain optimistic and are currently collecting signatures to officialize their status. Though they face much of the usual skepticism that plagues direct democracy-oriented efforts, they remain confident that the flaw is not in the concept but in the design of many pervading systems.

They see direct digital democracy as requiring the same kind of wave of innovation that has transformed many long-shot ideas into unquestionable parts of our daily lives.

After all, the precedent for such a radical change in behaviour abounds.

Online commerce was dismissed before E-Bay and Amazon got it right, and social networking required various iterations before Facebook and Twitter found what appear to be working formulas.

Just as Bitcoin may be a step towards a digital currency even if Bitcoin itself doesn’t become the gold standard (pun intended), so too does direct/digital democracy need a series of catalysts to find the structures and models that can both enable increased democratic participation and deter abuse and potential pitfalls.

After a wave of movements and revolutions across the world that were either fueled or accelerated by social media, the Net Party hopes to “open the bandwidth of democracy” by changing not only the people in charge but the structures they inherit. The ultimate goal is to shift political discussions away from debates about people and towards debates about issues.

Given that our current democratic systems were designed in a different era to solve different problems, the conditions are ripening for democracy to move past what MIT professor Cesár Hidalgo refers to as “one-bit democracy” in which citizens are allowed to contribute one bit of input every four years, to something along the lines of ‘Democracy 2.0’. Such a system needs to be capable of operating on its own with limited input whilst also sustaining and processing large surges of input when required.

Politicians such as the Argentine Finance Minister may just be making the case for the Net Party Founders on their behalf.

After all, it’s hard to convince people that they need politicians to defend themselves from themselves if the political class is regularly failing to provide the type of leadership, planning and policy required to ensure a country’s long term stability.

Having experienced more booms and busts than Van Halen, and with 89% of 18-29 year-olds in Buenos Aires accessing the internet every day, Argentina may just be the place for a new ripple in the wave of of democratic experimentation taking place across the globe.

With the Pirate Party making gains in Iceland and Partido X (The X Party) gaining momentum in Spain, The Net Party may just find itself one of many groups hoping to apply the disruptive potential of technology to breaking up monopolies of power within our governing systems.

At this point it is hard to say whether or not the Net Party will usher in a new era of Argentine democracy or if it will remain an easily overlooked fringe party. Nonetheless, the opportunity for change is real, and as Rahm Emanuel once said, “you never want to let a serious crisis go to waste.”

Disclosure: The author occasionally advises the Net Party.

Image credit: Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.