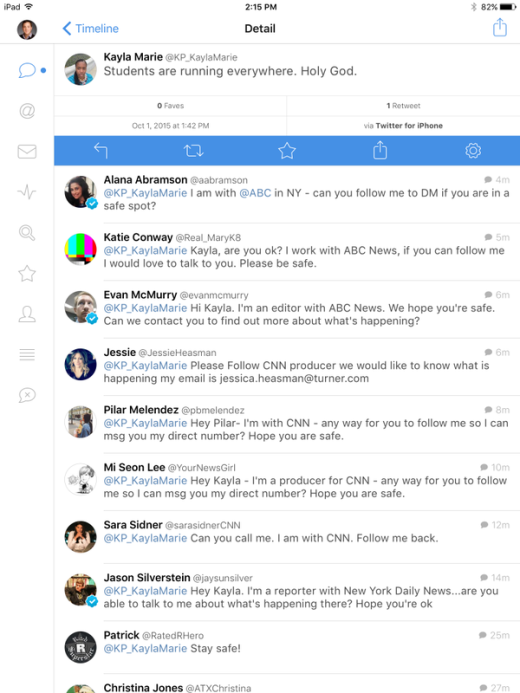

On October 1, there was yet another mass shooting. A student at Umpqua Community College shot and killed nine of his classmates and wounded nine others. During the shooting, a witness to the shooting tweeted “Students are running everywhere. Holy God.” Within minutes, she was inundated with requests for interview. Within a few more minutes, there was backlash against those in the media reaching out.

The media has been the public’s point of access to events we didn’t see ourselves for a really long time. Since the rise of the digital age, the media has unprecedented access to us, the witnesses (especially when we use the Internet to tell our story, in whichever form that may come). The speed of the news cycle has made it harder for people in the media to show compassion, especially in the wanton coverage of a shooting or bombing.

Given recent events, and my experience during and after the Boston Marathon Bombings, I implore the media to show more compassion for witnesses to these traumatic events. While I acknowledge that media publications aren’t nonprofits, it’s important to reevaluate how the media reaches out and follows-up with sources.

More than two years ago, I was hanging out of my second-story Boston office when the first bomb, the one almost on the marathon finish line, blew up directly under me. I was taking pictures at the time, and I took some immediately after — before we climbed out the back window and ran into the alleyway. I knew instantly that what I had just witnessed was too big for my brain to process and to remember accurately. I needed proof for myself and something to help me remember, so I took pictures before running out the back of the office.

I ended up writing a blog post that I thought was pretty good, so I sent it and some of the pictures I took to Deadspin. I got an email back that they were going to run my post.

Next, came an intense four days and a turbulent several months. I started getting Twitter DMs, LinkedIn messages and even emails to my work account from producers, editors and writers. I fielded inquiries from outlets and publications like the New York Daily News, ABC, the New York Post and more.

The messages, and now calls, from journalists were beginning to become overwhelming. I couldn’t sleep without being jolted awake from a nightmare of a bomb exploding at a child’s birthday party or at the restaurant where I was drinking with friends. I was a psychological mess, and made a mistake. I received a one-liner from the New York Post – “Can we use this picture.” I responded: “Yes.”

When my friend in New York City sent me a photo of the front cover of the New York Post, my stomach dropped. I wouldn’t have even recognized my photo if I had walked past a newsstand and saw it — it was so heavily cropped. I should have known better, but I wasn’t thinking. Too much was going on at once.

Credit: Deadspin

The cover began to go viral: it was featured on Colbert Report, The Huffington Post, the Columbia Journalism Review, The Week, Salon and more. Without thinking, I was complicit in harming people.

Four days after the bombing, and three days after my post published, I woke up to the news that there was a massive manhunt for one of the bombers, one was dead and they had killed an MIT police officer. After a day of sitting in front of the TV, hoping with all of my being that the authorities would capture this monster, they caught him. he media moved on from Boston, and from me and my photos.

In many ways, my experiences after the Boston Marathon are different than “Kayla Marie”’s in Oregon. I can’t know how she felt while the media tried to get in touch with her, and I’m not sure how she will feel over the next few months.

What I can say is that if you use the Internet to tell your story, whether you are trying to cope with what you just experienced or for some other reason, the media will try to reach you– and then discard you after they’ve gotten what they want and move on.

I can’t propose to change the way media outlets make their money or the ethics involved with reporting the news — I’m not an economist or an expert on the media. But, if they are going to sell coverage of these events, they need to think about what they are doing to their sources.

Telling the media to “treat interviewees with compassion” sounds platitudinous, impractical and maybe even a conflict of interest. But, I believe it’s possible and that the media has a responsibility to do so. If we can demand oil companies, drug manufacturers, etc., to enact certain standards that are contrary to their business interests, then we can demand the same from the media.

Practically, I urge members of the media to do a few simple things when reaching out to a witness to tragedy.

When it comes to breaking news, reporters should reach out with sympathy. A reporter’s time is limited, but they are reaching out to someone who just experienced what was probably the most traumatic experience of his or her life. What is going on in his or her head is something that the journalist might never be able to empathize with. So, tread softly.

While I would advocate for a journalist to hammer Tim Cook or Hillary Clinton with difficult questions, I’d argue that a traumatized witness deserves the benefit of the doubt. Members of the media need to ask themselves if they are taking advantage of their source. They might be ruining someone’s life.

Follow-up. Once the coverage hits, a journalist should follow-up with the source thanking them for telling their story. Then, a few months later, the journalist should check-in to ask how the interviewee is doing. The interviewer should make sure that the source knows that they were appreciated and that their story is not forgotten.

It’s possible that if Sam Biddle at Gawker, or Jason Silverstein of the New York Daily News or Barry Petchesky of Deadspin, were to read this article, they would say that a call for compassion in the current journalistic climate is naive and silly. They might be right, but I hope they aren’t. It’s possible that using the Internet as an outlet saved me after the bombing. But, it’s certain that being an object of media interest (and then a forgotten one) irreparably harmed me.

Read Next: The Ashley Madison suicides: It’s the hackers who should feel shame

Image credit: Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.