The “brain in a jar” is a thought experiment of a disembodied human brain living in a jar of sustenance. The thought experiment explores human conceptions of reality, mind, and consciousness. This article will explore a metaphysical argument against artificial intelligence on the grounds that a disembodied artificial intelligence, or a “brain” without a body, is incompatible with the nature of intelligence.[1]

The brain in a jar is a different inquiry than traditional questions about artificial intelligence. The brain in a jar asks whether thinking requires a thinker. The possibility of artificial intelligence primarily revolves around what is necessary to make a computer (or a computer program) intelligent. In this view, artificial intelligence is possible if we can understand intelligence and figure out how to program it into a computer.

The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes deserves much blame for the brain in a jar. Descartes was combating materialism, which explains the world, and everything in it, as entirely made up of matter.[2] Descartes separated the mind and body to create a neutral space to discuss nonmaterial substances like consciousness, the soul, and even God. This philosophy of the mind was named cartesian dualism.[3]

Dualism argues that the body and mind are not one thing but separate and opposite things made of different matter that inexplicitly interact.[4] Descartes’s methodology to doubt everything, even his own body, in favor of his thoughts, to find something “indubitable,” which he could least doubt, to learn something about knowledge is doubtful. The result is an exhausted epistemological pursuit of understanding what we can know by manipulating metaphysics and what there is. This kind of solipsistic thinking is unwarranted but was not a personality disorder in the 17th century.[5]

There is reason to sympathize with Descartes. Thinking about thinking has perplexed thinkers since the Enlightenment and spawned odd philosophies, theories, paradoxes, and superstitions. In many ways, dualism is no exception.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that dualism was legitimately challenged.[6][7] So-called behaviorism argued that mental states could be reduced to physical states, which was nothing more than behavior.[8] Aside from the reductionism that results from treating humans as behaviors, the issue with behaviorism is that it ignores mental phenomenon and explains the brain’s activity as producing a collection of behaviors that can only be observed. Concepts like thought, intelligence, feelings, beliefs, desires, and even hereditary and genetics are eliminated in favor of environmental stimuli and behavioral responses.

Consequently, one can never use behaviorism to explain mental phenomena since the focus is on external observable behavior. Philosophers like to joke about two behaviorists evaluating their performance after sex: “It was great for you, how was it for me?” says one to the other.[9][10] By concentrating on the observable behavior of the body and not the origin of the behavior in the brain, behaviorism became less and less a source of knowledge about intelligence.

This is the reason why behaviorists fail to define intelligence.[11] They believe there is nothing to it.[12] Consider Alan Turing’s eponymous Turing Test. Turing dodges defining intelligence by saying that intelligence is as intelligence does. A jar passes the Turing Test if it fools another jar into believing it is behaving intelligently by responding to questions with responses that seem intelligent. Turing was a behaviorist.

Behaviorism saw a decline in influence that directly resulted in the inability to explain intelligence. By the 1950s, behaviorism was largely discredited. The most important attack was delivered in 1959 by American linguist Noam Chomsky. Chomsky excoriated B.F. Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior.[13][14] A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior is Chomsky’s most cited work, and despite the prosaic name, it has become better known than Skinner’s original work.[15]

Chomsky sparked a reorientation of psychology toward the brain dubbed the cognitive revolution. The revolution produced modern cognitive science, and functionalism became the new dominant theory of the mind. Functionalism views intelligence (i.e., mental phenomenon) as the brain’s functional organization where individuated functions like language and vision are understood by their causal roles.

Unlike behaviorism, functionalism focuses on what the brain does and where brain function happens.[16] However, functionalism is not interested in how something works or if it is made of the same material. It doesn’t care if the thing that thinks is a brain or if that brain has a body. If it functions like intelligence, it is intelligent like anything that tells time is a clock. It doesn’t matter what the clock is made of as long as it keeps time.

The American philosopher and computer scientist Hilary Putnam evolved functionalism in Psychological Predicates with computational concepts to form computational functionalism.[17][18] Computationalism, for short, views the mental world as grounded in a physical system (i.e., computer) using concepts such as information, computation (i.e., thinking), memory (i.e., storage), and feedback.[19][20][21] Today, artificial intelligence research relies heavily on computational functionalism, where intelligence is organized by functions such as computer vision and natural language processing and explained in computational terms.

Unfortunately, functions do not think. They are aspects of thought. The issue with functionalism — aside from the reductionism that results from treating thinking as a collection of functions (and humans as brains) — is that it ignores thinking. While the brain has localized functions with input–output pairs (e.g., perception) that can be represented as a physical system inside a computer, thinking is not a loose collection of localized functions.

John Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought experiment is one of the strongest attacks on computational functionalism. The former philosopher and professor at the University of California, Berkley, thought it impossible to build an intelligent computer because intelligence is a biological phenomenon that presupposes a thinker who has consciousness. This argument is counter to functionalism, which treats intelligence as realizable if anything can mimic the causal role of specific mental states with computational processes.

The irony of the brain in a jar is that Descartes would not have considered “AI” thinking at all. Descartes was familiar with the automata and mechanical toys of the 17th century. However, the “I” in Descartes’s dictum “I think, therefore I am,” treats the human mind as non-mechanical and non-computational. The “cogito” argument implies that for thought, there must also be a subject of that thought. While dualism seems to grant permission for the brain in a jar by eliminating the body, it also contradicts the claim that AI can ever think because any thinking would lack a subject of that thinking, and any intelligence would lack an intelligent being.

Hubert Dreyfus explains how artificial intelligence inherited a “lemon” philosophy.[22] The late professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, Dreyfus was influenced by phenomenology, which is the philosophy of conscious experience.[23][24][25][26] The irony, Dreyfus explains, is that philosophers came out against many of the philosophical frameworks used by artificial intelligence at its inception, including behaviorism, functionalism, and representationalism which all ignore embodiment.[27][28][29] These frameworks are contradictory and incompatible with the biological brain and natural intelligence.

To be sure, the field of AI was born at an odd philosophical hour. This has largely inhibited progress to understand intelligence and what it means to be intelligent.[30][31] Of course, the accomplishments within the field over the past seventy years also show that the discipline is not doomed. The reason is that the philosophy adopted most frequently by friends of artificial intelligence is pragmatism.

Pragmatism is not a philosophy of the mind. It is a philosophy that focuses on practical solutions to problems like computer vision and natural language processing. The field has found shortcuts to solve problems that we misinterpret as intelligence primarily driven by our human tendency to project human quality onto inanimate objects. The failure of AI to understand, and ultimately solve intelligence, shows that metaphysics may be necessary for AI’s supposed destiny. However, pragmatism shows that metaphysics is not necessary for real-world problem-solving.

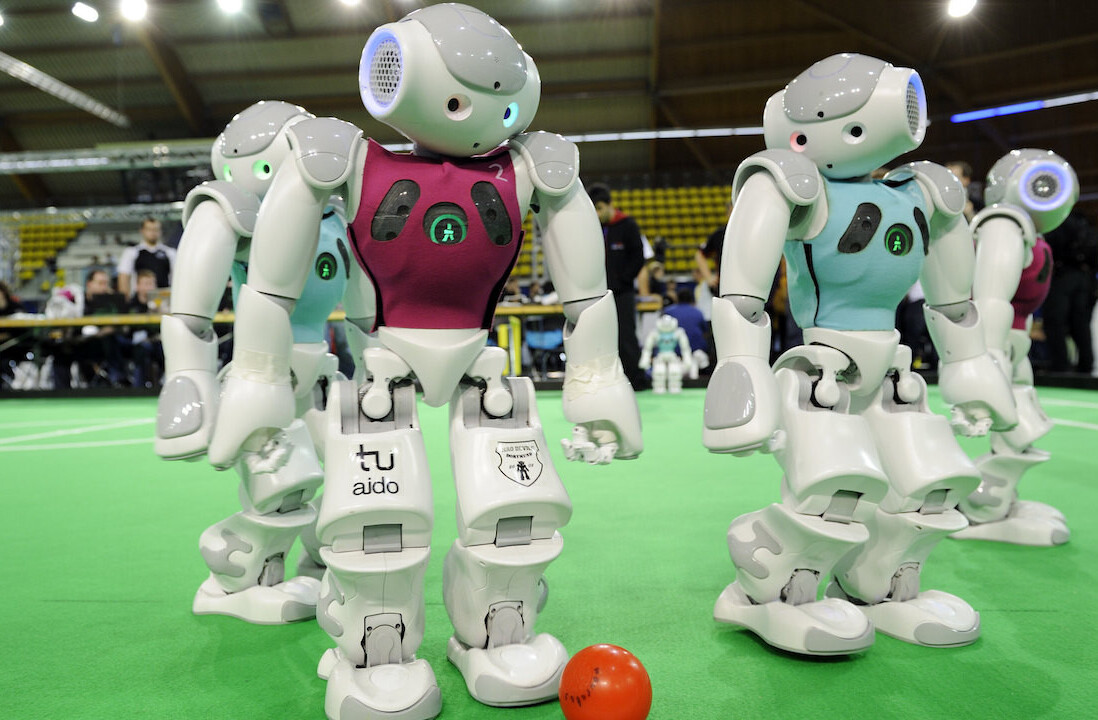

This strange line of inquiry shows that real artificial intelligence could not be real unless the brain in a jar has legs, which spells doom for some arbitrary GitHub repository claiming artificial intelligence.[32] It also spells doom for all businesses “doing AI” because, aside from the metaphysical nature is an ethical question that would be hard, if not impossible, to accomplish without declaring your computer’s power cord and mouse as parts of an intelligent being or animal experimentation required for attaching legs and arms to your computers.

This article was originally written by Rich Heimann and published by Ben Dickson on TechTalks, a publication that examines trends in technology, how they affect the way we live and do business, and the problems they solve. But we also discuss the evil side of technology, the darker implications of new tech, and what we need to look out for. You can read the original article here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.